The trumpeter, vocalist, bandleader, composer, arranger, producer, A&R man, and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee Dave Bartholomew passed away Sunday at age 100. He was, among many other things, a friend of the Ponderosa Stomp, and we are saddened by his loss and grateful for everything he shared with us.

For a deep dive into his canon, check out this piece by Michael Hurtt.

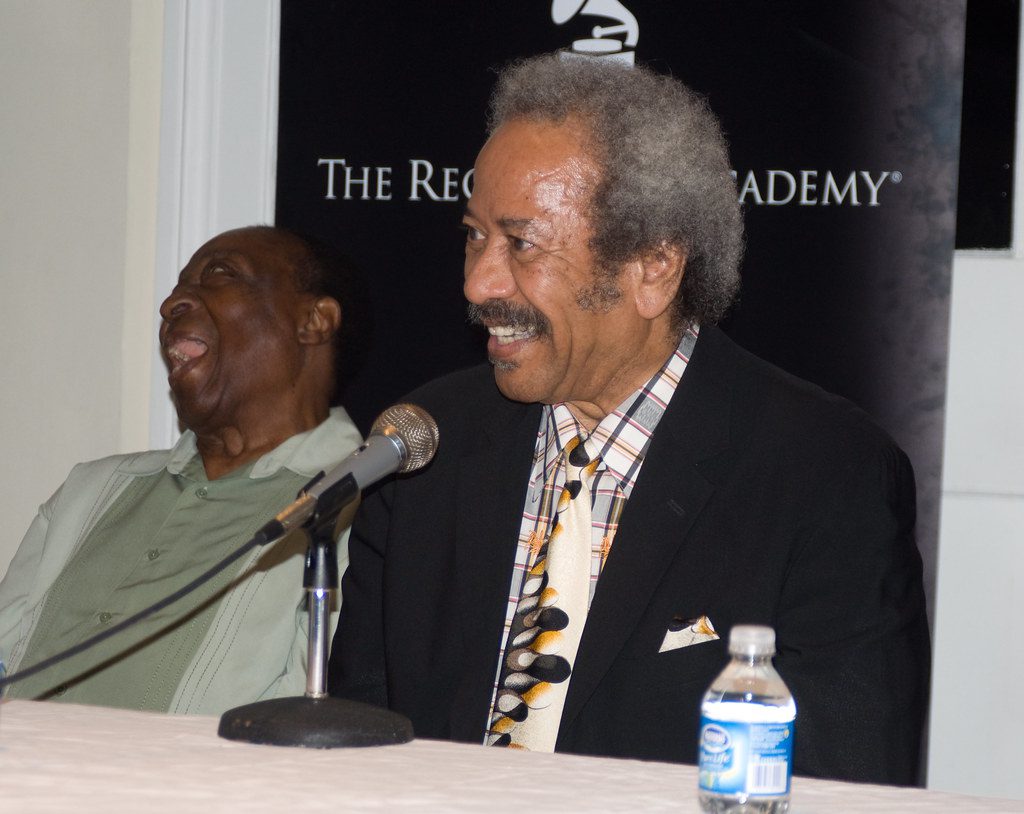

To hear Bartholomew himself in conversation with saxophonist Herbert Hardesty and our own Dr. Ike, check out this uncut oral history from our 2009 Music History Conference.

For a remembrance of our work with Bartholomew, we offer this from Jordan Hirsch, editor of ACloserWalkNola.com:

Dave Bartholomew Gets his Sound

I met Dave in 2007 in the wood-paneled rehearsal room in the old musicians’ union building in New Orleans (he was called by his first name reverently, like Leonardo.) The Ponderosa Stomp had invited him to front a band we put together with Wardell Quezergue after Hurricane Katrina to help elder R&B musicians get back to work. Wardell and Dave knew each other, but they hadn’t worked together all that much—typically there’s only one brilliant bandleader/arranger/producer in the room at a time. (In 1963 they collaborated on a fine instrumental album called “New Orleans House Party,” which came and went with little fanfare.)

We weren’t quite sure how the show would work. Dave was still displaced to Texas following the flood (he would move back home in 2008) and hadn’t performed regularly in years. We had to do some work to find musicians up to his standards. Part of his genius was for picking out talent, most famously Fats Domino and the J&M Studio house band, but he helped launch dozens of others, too, including Allen Toussaint. He always found the great among the good, and knew what he wanted to hear.

We were told that Dave was particularly demanding of drummers, which seemed fair enough for the man known as the architect of the “big beat” that came to define rock and roll. Early in his career he brought Earl Palmer from the Dave Bartholomew Orchestra into the studio, where he would go on to a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame career of his own. It was Palmer’s backbeat—a wallop on beats two and four—that influenced drummers across the country. Dave also worked with Joseph “Smokey” Johnson, whose sound was so fat that drummers at Motown Records tried to achieve it with two drummers playing at once. In 2007 there were only a couple of drummers Dave would consider working with. We tapped Bernard “Bunchy” Johnson (no relation to Smokey).

The rehearsal at the musicians’ union began with Wardell running through a few songs with the group he’d been working with over the previous year. He was blind from diabetes so he conducted the band without making eye contact with the musicians. He didn’t have to—they knew he heard precisely each note they played, and they wanted to hit them all for him. When it was time to run through Dave’s set, Bunchy got behind the drum kit and a few additional horn players pulled up chairs to the row of music stands in front of him. Dave stood in front of the band and the musicians dug in like sprinters at their starting blocks. Bunchy was easy-going, seeming perpetually on the verge of breaking into a grin. But when Dave kicked off the first song his face stiffened in complete focus, and he hit so hard he quickly broke into a sweat.

Dave had been known as a “taskmaster” since the late 1930s. He adopted the no-nonsense style of band leadership from Fats Pichon, whom he played for on riverboats as a teenager. Wielding authority was another of Dave’s gifts, and it was essential to the development of rhythm and blues in New Orleans. It is often remarked that he got the best out of Fats Domino, who, left to his own devices, could be unfocused in the studio. More broadly, as an A&R man and a producer, Dave showed the record industry that the city’s musical talent—which has always been abundant—could be shaped into a viable product in the postwar era. After he cut “The Fat Man” with Domino in 1949, record men started showing up in New Orleans looking for the next hit.

In 2007, in the wood-paneled practice room, Dave circled the musicians slowly while they played, going behind Bunchy and around to the horn section. We’d added a few pieces to Wardell’s band, including saxophonist Herbert Hardesty (link to Stomp bio), who’d worked with Dave since “The Fat Man.” On many of Domino’s hits Hardesty played solos of his own devising—Dave knew when a song would be served best by stepping back to let talented people let play what they felt.

Before he was a bandleader or producer Dave had been a horn man himself, inspired by Louis Armstrong (he played trumpet well into his 90s). He honed his skills under Clyde Kerr, Sr., who also taught Wardell and other future stars of the R&B era. At the rehearsal in 2007, when a recently added trumpet player, Roussel White, started to solo, Dave eased into his space and bent down to look him in the eye. “Come on!” he said, exhorting him. “They told me you had chops!” White closed his eyes and blew hotter. After rehearsal I asked someone who knew Dave if it was normal for him to get in the face of a musician he didn’t know. Dave knew the trumpet player, I was told. As a matter of fact, they were related.