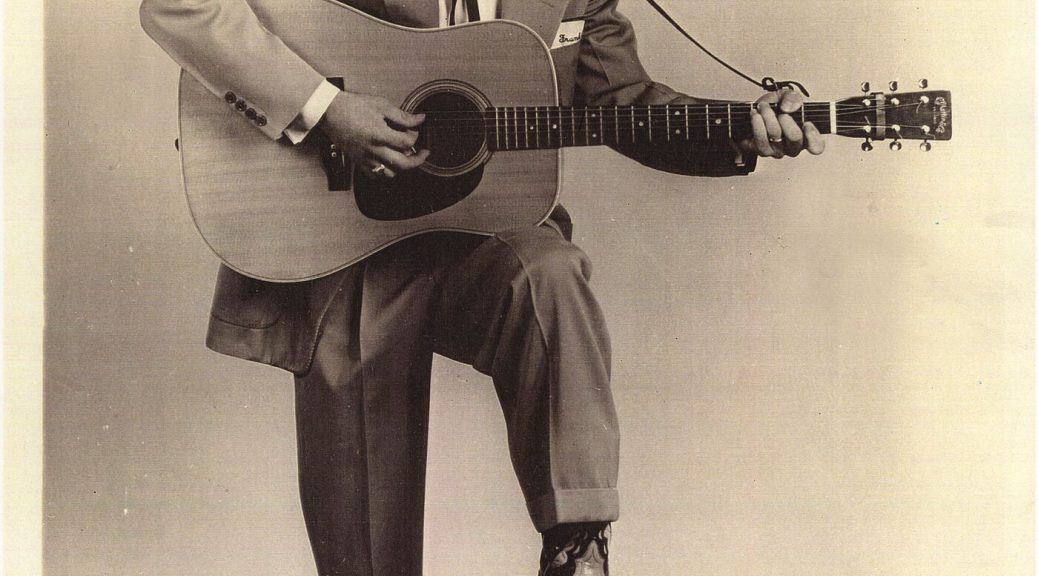

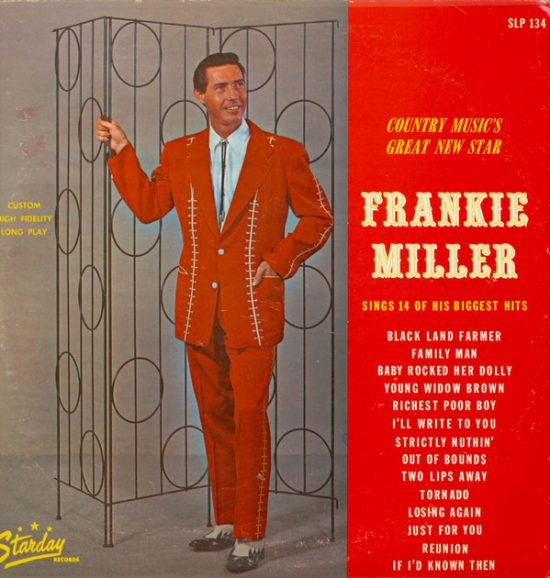

“Well, I was born in a cave/ I was raised in a den/ My chief occupation’s taking women from the men/ I’m a true blue papa/ Gonna have a ball tonight…” When these lyrics came booming out of jukeboxes across Texas on the flip side of Frankie Miller’s hit “Black Land Farmer,” you knew you were hearing the penultimate in hillbilly music. Recording for the renowned Starday label, in “True Blue” Miller scored the imprint one of its biggest hits, and even more importantly, burned the honky-tonk ouvre into the minds of millions worldwide. The song wasn’t one of the best, it was the best.

—

Quite a few mainstream country performers temporarily hopped on the rockabilly bandwagon when it rolled through the South during the mid-‘50s, including Webb Pierce, Marty Robbins, George Jones, Ferlin Husky, and Buck Owens, the last three under aliases because they didn’t want to be publicly associated with rock and roll. Frankie Miller refused to follow their lead. The Texas singer was a devoted disciple of the great Hank Williams, and he wasn’t about to change his long-held musical allegiance just to embrace a temporary trend.

“That’s what I loved, and that’s what I stayed with,” says Miller, who had to cope with some hard times because of the seismic shift that Elvis and his legion of teenaged followers wrought. “Man, you couldn’t give a country song away, hardly,” he says. “Rock and roll came in so strong, it just shut us out. You’d walk in a radio station with a country record, they’d kick you out the door! They wouldn’t really do that, but they sure wouldn’t give you much attention.”

More than six decades later, the 86-year-old Miller remains a proud purveyor of hardcore Lone Star country. With Johnny Rodriguez’ longtime pianist Gary Goss joining him, Frankie headlines the Ponderosa Stomp’s Texas Honky Tonk Revue on Saturday evening, sharing the bill with Darrell McCall and James Hand–and you can bet that Miller’s grasp of the genre is as sure-handed as ever. Having all but walked away from the business during the mid-‘60s to work as a service manager at an auto dealership, Miller can testify that performing is a lot sweeter the second time around.

“I got off the road altogether. I didn’t even listen to music for about 30 years almost, from about ‘65 to about ‘95,” he says. “I just got tired of it. I was so much on the road. I had a wife, and I had these two little girls. I said, ‘What the hell am I doing, running around all over hell? I’ve got a family back in Texas.’ So I just told them to stick it. And I went home. I went back to Texas and stayed here for 25 years. Oh, I worked a little bit, but not anything on the road at all.”

RAILROADS, ERNEST TUBB, AND HANK WILLIAMS

Victoria, Texas, where Frankie was born, lies between Houston and Corpus Christi, not far from the Gulf Coast. “My daddy was a railroad engineer for 47 years on the Southern Pacific Railroad,” he says. “I rode the train with him a lot. I really loved the trains, boy. I really loved those steam engines. That’s what he ran all the time when I was growing up. His daddy, which was my grandfather, which I never knew, was a Texas Ranger. He died when my daddy was eight years old, so I never knew him, My grandfather on my mama’s side, he was a blacksmith in a little town called Smiley, Texas. He was the only blacksmith.”

There wasn’t a whole lot of country music in Victoria’s air during Frankie’s early youth. “When I grew up in the war years, it was big band stuff, which I still love. I love the big band sound. I really do. Like Harry James, Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey,” says Miller. “That’s all we danced with in the schools when I grew up. We’d have our little dances there at the gymnasium, and it was all the records—it was just big band stuff, pop stuff. There was no country at all.”

That changed when Frankie was in his late teens. “I always listened to (country music) on the radio,” he says. “My brother, he was a big Ernest Tubb fan. He used to get up every morning at, I think it was 7:30, and listen to Ernest. Ernest came live from San Antonio when he was young. He was on a station called KONO in San Antonio. And my brother played guitar, and I just got interested from him. And we formed a little band. We had a little dance band there for several years.”

Older sibling Norman Miller was a devout Tubb fan, but Frankie preferred the sound of Hank Williams. “I really liked Hank when I was young, the feeling he put in his songs,” he says. Williams wasn’t Frankie’s only influence; he also dug Floyd Tillman, the distinctive Texas-based singer who scored major late ‘40s hits with “I Love You So Much It Hurts” and “Slippin’ Around.” “He was one of a kind,” says Miller. “He would shake his head while he was singing. Nobody did it like Floyd.”

The Miller brothers assembled their own outfit and began playing locally as well as holding down a program over KNAL. “He played rhythm guitar in the band I had, the Drifting Texans,” says Frankie. “Ernest and them started making headway, and there were some bands formed. And I went ahead and got me a band going, and we done real good. We played about five nights a week. Played for a guy Fort Lavaca, Texas, named Travis Jacobs. He had six or seven clubs, and we worked one of them every night for five nights. So we had plenty of work.

“When I had my band, I had a daily show, five days a week, from Victoria. We had a 30-minute program every day at 12 noon. They would pick it up there in Smiley. It was a 500-watt station, but hell, it went out to everywhere we played. They got the station. My grandpa and grandma, they would listen to it on the radio. I’d say, ‘I’m comin’ down there, Grandma!’

“We had a radio announcer there in Victoria that done all of our shows. We would record them on Sunday. We’d come in with the band on Sunday, and tape them. Tape five shows on Sunday and then play them once a day during the week. And this radio announcer named Charlie Lewis, he advertised for us. What I did, I made him part of the band. Mostly when we were playing, we played for the door. We had some guarantees, but mostly it was for the door. And I put Charlie Lewis right in there as a member of the band. He got a cut just like the musicians did. Same cut. And he advertised for us. Boy, those other bands around there, they were just wondering why in the hell’s he’s advertising so much for us. Man, we were covering them up. We had better crowds than any of ‘em because I had old Charlie Lewis on our side, advertising for us. That was one of the best marketing deals I ever did.”

MOVING ON TO HOUSTON

Eventually Houston’s bright lights and swinging nightspots beckoned. “I always drove to Houston,” says Miller. “I lived about 100 miles from Houston, and when they’d have somebody there that I would want to see, like Ernest would be there, or Hank Williams, me and my brother would always drive to Houston. And they usually were playing at a place called Cook’s Hoedown Club, which was right in downtown Houston. We’d go and see who we wanted to see. Anybody that’d come to Houston that we wanted to see, we’d drive there and see ‘em.”

One joint where fistfights and great music by singer Eddie Noack were both in abundant supply was particularly noteworthy. “Eddie was playing for a guy named R.D. Hendon,” says Miller. “He was a drummer, but he didn’t do much. He owned a big club there in Houston, upstairs. It was called 105 ½ North Main. They gave it the half because it was upstairs, but it was great big. The whole upstairs was a club. 105 ½ North Main—they used to call it One-O-Fight-and-a-Half North Main, it’d get so rough up there. They were fighting all the time.

“Harlan Haas, my cousin, lived in Houston there. Me and him went up there one night. We were walking up the stairs, and this bouncer was coming out the top door there, and he had a guy by the seat of his pants and he threw him down the stairs,” he continues. “We were trying to get up the stairs to come in the club to hear Eddie, and this guy was rolling down the stairs and we had to dodge and get out of the way. And the old bouncer up there, he saw us trying to come up there, and he said, ‘Hey, you boys! Come on up and have a good time!’ My cousin Harlan said, ‘Maybe we ought to come back another night.’ The guy was rolling down the stairs, man. We had to get out of the way to keep from getting hit. We went on up. Had a good time. I always had a good time with Eddie. I liked Eddie’s writing, and I liked Eddie’s singing.”

PAPPY DAILY AND GILT-EDGE RECORDS

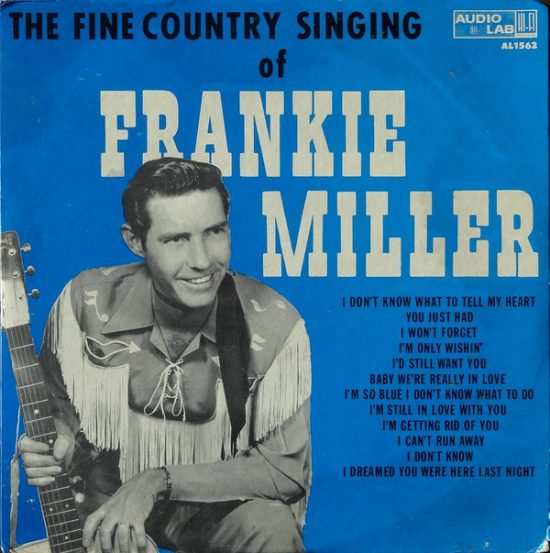

Before long, Frankie was sufficiently seasoned to look into making records of his own. “Pappy Daily there in Houston had a big distributorship called South Coast Amusement Company,” he says. “It was the biggest distributorship in Texas. And we cut these things, and he listened to them. He had an in with 4 Star Records out in California with Bill McCall, so he said, ‘I think we can get ‘em on there.’ So he sent them out there, and Bill liked them, so he put them out. My first record was in 1951, two years before Hank died.” Miller wrote all four songs he waxed at his first date at Bill Holford’s ACA Studios in Houston, McCall pressing up “I Don’t Know” and its flip “I’m Getting Rid Of You” on his Gilt-Edge subsidiary as the debut platter of of Frank Miller and the Drifting Texans.

“I’m Only Wishin’,” another self-authored number from Miller’s encore Gilt-Edge session later that year, proved a regional hit. “I don’t think I had anything that inspired me on that,” says Miller. “I just started writing.” The Drifting Texans featured some fine musicians (Frankie played his own rhythm guitar). “I had some guys out of Houston there that worked for me in the band,” he says. “Jack Kennedy played piano. He was a good piano player. His brother Shang played upright bass. Had a guy named Jimmy Summey that played steel. He’d worked some shows with Hank on the road. He’d worked at the Louisiana Hayride when Hank was on the Hayride, and during the week he went out on the road with Hank and played. That’s before Hank had his Drifting Cowboys going. So Jimmy was a fine musician. He was a good steel man. He was on lap steel.”

Miller wrote quite a few of his half-dozen Gilt-Edge singles. “I took that up really from Hank Williams,” he says. “I knew Hank wrote most of his stuff, and wrote a ton of real good songs, Hank did. I wanted to be more like Hank. That’s the best way to get anything done anyway in the country music business back then, was write your own songs.”

Frankie’s last Gilt-Edge session at ACA in late ‘51 or early ‘52 was unusual in that it contained two Williams covers, including “Baby We’re Really In Love.” “Me covering Hank!” laughs Miller. “Pappy had this big South Coast Amusement Company, and Hank put out this record. And something happened to the pressing plants, and they couldn’t get ‘em out. Man, he was just swamped. They were playing it on the air, you know. He was just swamped with people wanting to buy it, jukebox operators and everything. He sold mostly to jukebox operators. So Pappy got me in the studio and said, ‘Hell, we’re gonna recut it!’ So we were in the studio and we cut the thing. He sent it out to 4 Star and they put it out, and we beat Hank out with it!”

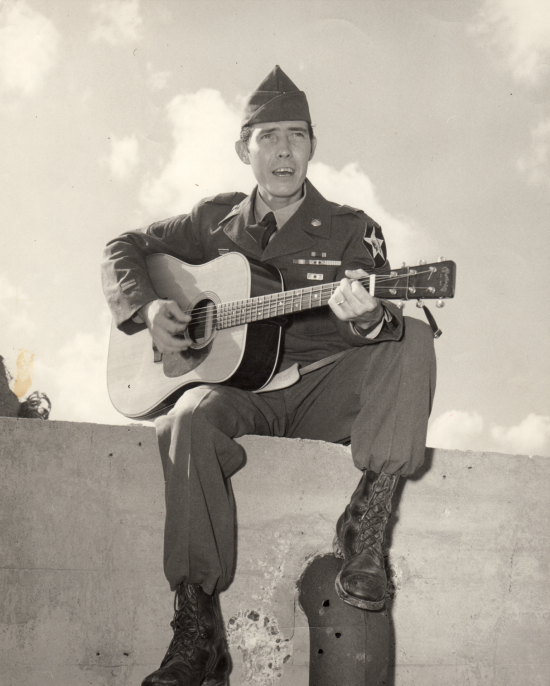

ARMY LIFE

Decca Records was poised to sign Frankie in 1952 when Uncle Sam intervened. “I just about had the deal worked out,” he says. “That guy in Dallas that handled a lot of Lefty Frizzell’s songs and helped Lefty on record, Jim Beck, he was the one that was doing this for me, and Travis Jacobs, a friend, took me up there. And we cut a session there at Jim Beck’s studio. And Jim had it going. He just about had it ready to sign, and I got drafted. That ended that deal.”

Initially stationed at Camp Roberts in central California, Miller assembled a band on the Army base that included steel guitarist Sonny Trammel. “We were both in training out there. We’d play on the weekends, and sometimes even during the week we’d play at the Officers’ Club, maybe, and the NCO Club, the Non-Commissioned Officers’ Club. They’d always want some kind of music going, those clubs would. We had a good time doing that.

“We took Ray Lachte on,” says Miller. “He wasn’t in the Army! We needed a guitar man. Ray was a musician around Nashville. He knew Sonny real well. So Sonny called him and said, ‘Man, get on out here! We’ve got a good band going!’ So he got there with his guitar. And hell, we were in the Army, so we didn’t have a dime. We took him on the base, got him on the base and took him in our barracks there. We put him in our fatigues, and he went to the chow hall with us and everything for three months or more and was never in the Army! Nobody ever knew it. Nobody knew it at all. He would sleep in our barracks, and there wasn’t anybody in there during the day. We’d fall out for chow, and he’d be right with us. As long as you didn’t have any trouble, nobody was going to say anything. Hell, everybody thought he was a regular GI!

“We kept him on the base there with us. We’d fall out for detail in the morning, where we’d all get out there and have to pick up cigarette butts and stuff off the ground and keep the place policed, and he’d be right out there with us. I don’t know what they’d have done to us if they’d have caught us. Probably not much. They’d have kicked his butt off there is about all they’d have done.” Ultimately Miller was shipped off to Korea to fight in the war that was raging at the time. Fortunately, there was enough leisure time between skirmishes for Frankie to write some fresh material.

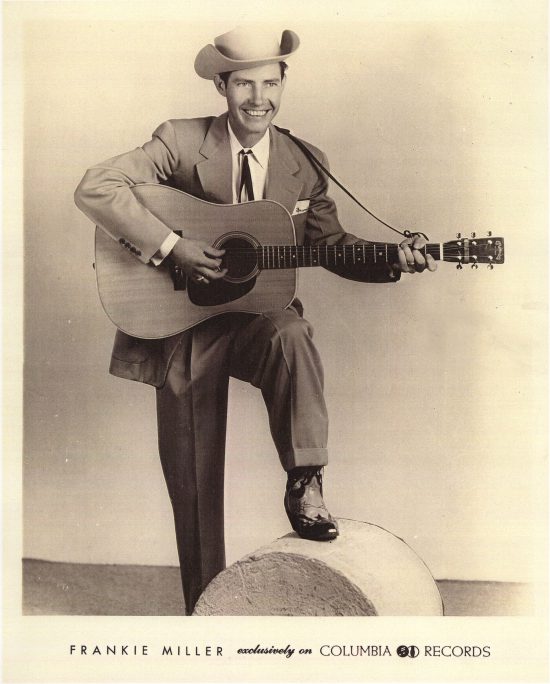

COLUMBIA RECORDS

When he returned stateside in 1954, Miller recorded the songs he’d written in Korea for his new label, Columbia Records. “Don Law was the A&R man at that time. We cut a lot of stuff there at Beck’s. He brought Carl Smith down one session and cut him. He had Marty Robbins cut there. A number of his artists cut there,” says Miller. “Jim had a good studio. He had a good sound. I liked it quite a bit better than recording in Houston. I thought the sound was better.”

One of the numbers he dreamed up in Korea, the up-tempo “It’s No Big Thing To Me,” was on the schedule at Frankie’s first Columbia session in July of ‘54, Miller sharing rhythm guitar duties with future country star Billy Walker. “That was a saying we had over there,” he says. “Like a guy would be, something would happen, some little old thing made him mad, and he’d be all mad. One of us would come and say, ‘Oh, that’s no big thing. That’s no big thing.’ That was a saying that everybody used in Korea, all the GIs used that. ‘It’s no big thing.’ And that’s how I came about to write the song. I said, ‘Hell, that’s a good title for a song!’” The other side of the single, released as by Frankie Miller rather than Frank as he’d been billed on all of his Gilt-Edge platters, was another buoyant Miller original, “Hey! Where Ya Goin’?”

Back at Beck’s Dallas studio that December with Law again at the helm and Trammel on lap steel, Frankie waxed four more titles that all saw light of day at the time, and he returned in October of 1955 for a third Columbia date with Sonny again on hand and a totally unknown Willie Nelson on rhythm guitar along with Miller (Jimmy Rollins played lead). Along with Frankie’s own catchy “Paint, Powder And Perfume,” one of the four tunes waxed that day was veteran country songsmith Cindy Walker’s “I Don’t Know Why I Love You.”

“I went down to Cindy’s house. I was going to a session. I needed some material. And Don Law was a good friend of Cindy’s, so he sent me down to Mexia, where she lived there, down below Dallas. Mama was still alive then. They were living there in Mexia. Mama was living with her, her mama. That’s what she called her. That’s all she called her, was Mama, so that’s what I’m calling her. She sang me a bunch of songs, and I liked that better than the rest of the. So I cut that song,” recalls Frankie. “It was a pretty good song.”

WEBB PIERCE

With rockabilly coming on strong, Columbia dropped Miller after his five singles for the major label failed to chart. But he did write a winner for country star Webb Pierce in 1955; “If You Were Me” was tucked on the opposite side of Pierce’s smash “Love, Love, Love.” “I worked a lot of stuff with Webb when I was coming up. I moved to Nashville, and Webb had his own booking agency,” says Miller. “Webb owned Cedarwood Publishing Company, and he published that song, ‘If You Were Me And I Were You.’ And then I started booking through his agency there.

“I’ve heard so many stories about Webb. To me, he was a great guy. I never had any problem with him. Me and him hit it off so good. I don’t know how much of the stuff I heard was true about him, about him being such a bigshot and all that,” says Frankie. “He wasn’t like that to me. He was a great guy. He cut two of my songs and paid me, and through his agency booked me a lot. I worked a lot of shows with Webb as a headliner. We used to go through Canada. Of course, he was really hot back then. He was about the number one artist at one time.

“That’s the first time I met the old Stuttering Boy, Mel Tillis. He had an office there in Webb’s publishing company, Cedarwood. He had an office, and I walked in and saw him. I didn’t know him, but I saw the wall in back of his desk, he had a great big bass mounted there. It was what they called a Florida bass. And I went in and started talking to him about it. I like to fish too. And he was telling me about catching fish. We got to be good friends.”

MEETING ELVIS

Although rockabilly admittedly wasn’t Miller’s cup of tea, he knew talent when he saw it on the stage of the Louisiana Hayride in Shreveport, where Frankie frequently appeared. That’s where he first laid eyes on Elvis Presley. “My daughter, in ’55, she was six months old. She was born in February of ’55, so that was about August of ’55. And I had her backstage there,” says Miller. “I was carrying her down the aisle, and Elvis was coming the other way, meeting me. He stopped and said, ‘Frankie, that sure is a pretty little boy you got there!’ I said, ‘Well, Elvis, it’s a little girl!’ He laughed and said, ‘Can I hold her?’ I said, ‘Yeah!’ He held her and shuffled her around a little bit and gave her a little kiss and handed her back to me. I told my daughter about it when she got big enough to understand. She said, ‘Dad, I can’t understand why you didn’t get a picture of us!’ I said, ‘Well, we didn’t have cell phones back then. That’s why we didn’t get a picture.’ I didn’t have a camera with me. But that’s right—Elvis held her and gave her a little kiss.

“I don’t think anybody could ever think he could be anything but a big-timer. He would tear that whole Hayride up when he hit that stage, man. We always used to laugh that, hell, he closed the Hayride down! Before Elvis came there, we had an all-country show, and the crowd was all country-loving people. When Elvis hit there, it changed into rock and rollers, most of ‘em. And I said, ‘Hell, when Elvis left, we didn’t have anybody. We’d already lost all the country folks, and when Elvis left, they didn’t have any rock and roll people either!’

“We still had a good show after he left though.”

THE LOUISIANA HAYRIDE AND THE GRAND OLE OPRY

Indeed they did; broadcasting over the airwaves of KWKH from the stage of Shreveport Municipal Memorial Auditorium, the Hayride frequently showcased the likes of Johnny Cash, Nat Stuckey, and Johnny Horton when Elvis wasn’t around and was considerably more amenable to rockabilly than the Grand Ole Opry.

“I really liked the Louisiana Hayride. Backstage and all, it was kind of a family show. And so was the one here in Fort Worth, the Cowtown Hoedown. And I worked the Big D Jamboree in Dallas,” says Frankie, who would accrue plenty of experience performing at the Opry as well.

“When I lived in Nashville, I did the Opry every Saturday night that I was in town,” he says. “They were really governed by the union. Man, the first time I done the Opry, old Faron Young—we were on one side of the stage, and there was a guy standing over there with a clipboard. He said, ‘You’ve got to go over there and clear your songs with him.’ I forget the guy’s name, but he was there for years, and he was an Italian guy, a gruff-talking guy. So I went over there and I just stood there. He was talking to somebody else, then he looked over there at me several times. Finally, he said, ‘You on the show tonight?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ He said, ‘Well, come over here and tell me what you’re gonna sing. Does it have anything about beer in it, or drinking?’ I said, ‘No, it doesn’t.’ He said, ‘Well, you look like you’re scared to death!’ I said, ‘Hell, I am—especially after talking to you!’”

HOWARD CROCKETT AND “SUGAR COATED BABY”

In search of a new recording contract, Frankie cut five demos in 1956 at Clifford Herring Studio in Fort Worth. “It was some songs that Howard Crockett and a guy named Bob Graves wrote,” he says. The bounty incldued Crockett’s “Sugar Coated Baby,” soon recorded by Johnny Horton. “That was the demo he used to learn the song,” says Miller. “He was a good friend of mine, Howard was. He lived right in Fort Worth, and we did a lot of things together. Every time we went to Nashville, just about, we went together. We drove up there. He had songs that he was plugging all the time. He had really good luck with Johnny Horton. Johnny cut four or five of his songs. He sang a lot like Johnny, or Johnny sang a lot like him. I don’t know which one it was.”

“BLACK LAND FARMER”

Nine years into his recording career, with a load of fine recordings under his belt, Frankie had yet to crack the country and western hit parade. When he finally did, it came on the earthy “Black Land Farmer,” a true-life song that he cut in Houston in 1956 but initially couldn’t find any takers for.

“I wrote that about an old uncle of mine. His name was Louie Sauer. Sauer was his name. This was my mother’s brother,” says Miller. “He farmed all his life, and most of the time with mules. He used a tractor maybe the last couple of years he farmed. He never got rid of his mules. He kept those mules until he died.

“I cut the thing in Houston myself. Most of it was my band. My brother played coconut shells. That horse cloppin’, that was my brother using coconut shells on a pillow to make it sound like plowed ground,” he says. “We cut it at Gold Star. Bill Quinn (engineered) it. George Jones cut his early stuff there with Quinn at Gold Star.” For more than two years, Frankie tried to interest labels in the song with no success.

“I just quit pitching it to anybody, because that rock and roll was so strong. We went to Nashville, me and Howard Crockett, and it was in the car,” Frankie remembers. “We were playing some songs for Tommy Hill. Crockett had wrote some rock and roll kind of stuff, rockabilly. He was playing some stuff for Tommy Hill, and Tommy was working for Starday. Crockett said, ‘Tommy, you want to hear a good country song?’ Tommy said, ‘Yeah! Heck, yeah!’ And Crockett said, ‘Go down and get that “Black Land Farmer” out of the car, Frankie.’ I said, ‘Aw, hell, they don’t want to hear no damn country song!’ And he got up and pointed that old big long finger at me and said, ‘Go down there and get that song!’ So I did. I went down and got it. And man, Tommy just absolutely flipped out. He took it right to Don Pierce, and the next day I had a contract.”

Pressed up on Starday, “Black Land Farmer” did what all those great prior recordings of Frankie’s inexplicably couldn’t achieve—it gave him his first major C&W hit during the spring of 1959 (Miller also penned the rousing flip, “True Blue”). The barriers had finally fallen, and Frankie followed it up with another smash that autumn, “Family Man.”

“FAMILY MAN”

“A guy named Bobe (Balthrop) here in Fort Worth wrote that song—wrote it for me after I had ‘Black Land Farmer.’ He was a friend of mine. He was a Fort Worth police officer and a musician. He wrote songs, and after I had such success with ‘Black Land Farmer,’ he wrote this song as a followup for me called ‘Family Man,’ which was a damn good followup song. It was really a good song. He nailed it,” says Miller. “He really pinned some good stuff in that song.” The banjo-driven “Poppin’ Johnny” on the flip was a bit like one of the catchy saga songs that Horton was then enjoying so much success with. The success of “Family Man” got Frankie on Jubilee USA, the Red Foley-hosted ABC-TV program out of Springfield, Missouri (he performed “Black Land Farmer” as well as his then-current hit).

“BABY ROCKED HER DOLLY”

Merle Kilgore, one of the many Shreveport country artists to appear regularly on the Hayride, was responsible for Miller’s next Starday hit in 1960, although it actually came to Frankie through Horton’s largesse. “Johnny taught me a song called ‘Baby Rocked Her Dolly.’ Man, what a good song that was. I was going to record and I needed some material,” says Miller. “We were all on the Hayride, and I asked him if he had anything laying around that he wasn’t gonna do that I might be able to do. He said, ‘Man, I’ve got a hit song for you! Merle Kilgore wrote it.’

“Merle was there in Shreveport at the time. He was on a little radio station right outside of Shreveport in a little town there. He was doing his show there. And he came down on Christmas—Merle said, ‘I came down the stairs, and there’s my three kids down there, one of ‘em doing the jig, one playing the drum, and one rocking her dolly. That’s why I wrote the song, and how I wrote it.’ Which was a damn good song. I had an acetate demo, and we were doing some shows around there with James O’Gwynn and George Jones. I played it for ‘em one night, and George just—his eyes just lit up. He said, ‘Man, boy, I wish I’d have got that! You’ve got yourself a hit song there, brother!’ He liked it.”

“Merle was there in Shreveport at the time. He was on a little radio station right outside of Shreveport in a little town there. He was doing his show there. And he came down on Christmas—Merle said, ‘I came down the stairs, and there’s my three kids down there, one of ‘em doing the jig, one playing the drum, and one rocking her dolly. That’s why I wrote the song, and how I wrote it.’ Which was a damn good song. I had an acetate demo, and we were doing some shows around there with James O’Gwynn and George Jones. I played it for ‘em one night, and George just—his eyes just lit up. He said, ‘Man, boy, I wish I’d have got that! You’ve got yourself a hit song there, brother!’ He liked it.”

Jones teamed with Miller to write its flip side “Rain Rain,” which was about as close to rockabilly as Frankie ever got. Somehow Starday left a third collaborator’s name off the single. “It was a rainy, rainy night when we wrote the thing. Tell you who done the biggest part of it was J.P. Richardson, the Big Bopper,” says Frankie. “He was just an old country boy that hit it big with a song. There wasn’t anything rock and roll much about him at all. He was a country boy. He did country disc jockeying. Wrote some good country songs. George recorded a song that he wrote, ‘Treasure Of Love.’ It was a good song for George.

“(His name) should be on there because it was his idea and all. We just filled in some words and finished the song. I never sang that song at all after I recorded it but one time. That was on the Louisiana Hayride one night that I sang it. I don’t know why—it just didn’t do much for me. But a lot of people like that song, ‘Rain Rain.’ If you play the record, you can hear that’s Pig Robbins playing piano, and that’s Grady Martin on guitar. Just about everybody was the same as they done on ‘White Lightning.’ It’s got a lot of ‘White Lightning’ coming through that song too.”

“A LITTLE SOUTH OF MEMPHIS”

There was another trip to the C&W hit parade for Frankie with his 1964 Starday single “A Little South Of Memphis.” Its authorship was split between Miller and Hill, whose input was limited to one word. “Tommy really didn’t write anything on that,” says Miller. “See, I wrote the song and recorded it. The song, the way I wrote it, it was called ‘A Little South Of Dixie.’ That’s what I wrote it as, ‘Dixie.’ He said, ‘Why don’t we change the name? Hell, nobody knows where Dixie is! Let’s put a town in there where people know where we’re talking about.’ And I said, ‘I think that’s a damn good idea!’ So I cut him in for half of it.” The flip side was a revival of Noack’s “Too Hot To Handle.” “(Eddie) said of all the cuts that he had on ‘Too Hot To Handle,’ he liked Frankie Miller’s the best. When I cut it on Starday, you know. We had a good cut. The steel and the guitar were really good on that song.”

BACK IN HARNESS AFTER 30 YEARS OFF

After three decades of Miller barely dabbling in singing, Tracy Pitcox, the boss at Heart of Gold Records, got him interested in music again. “He was having some thing, and he invited me to it. He gave me what they called a 25-year award, and had me come there and say a few words.

“He said, ‘Man, I want to record you!’

“I said, ‘Oh, heck, you don’t need to record an old guy like me.’

“‘Yeah, I want to record you!’

“Man, he just pressured me into doing it, you know. I’ve been recording with him ever since. I’ve really had some good times doing shows this time around, because I didn’t have to worry about it. I’d just get on the show and sing. I wasn’t worried about making a living or nothing. I was just singing for fun, having a good time.”

That’s exactly what you can expect when Frankie Miller brings his Texas honky-tonk country to this year’s Ponderosa Stomp: a mighty good time!

–Bill Dahl