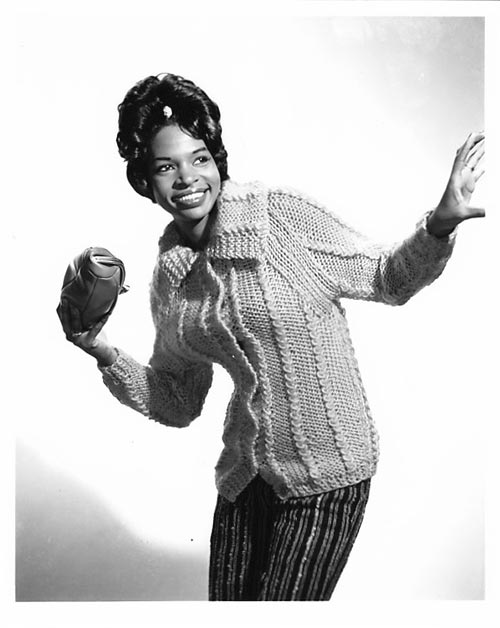

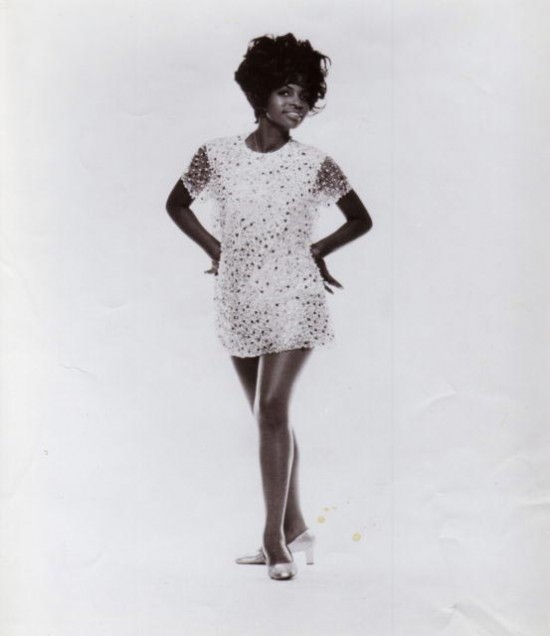

One of the most seductive R&B chanteuses of the 1960s, Maxine Brown was the captivating embodiment of the sophisticated, pop-slanted uptown soul sound. A frequent habitué of the R&B hit parade for much of that decade, Maxine’s gospel-rooted approach fit the immaculate production techniques then defining New York’s soul approach like a stylish satin glove.

Born August 18, 1939 in Kingstree, South Carolina, Maxine was a little girl when her family relocated to the Queens borough of New York City. There she honed her vocal skills inside the sanctified walls of Bethel Gospel Tabernacle Church. “I was raised up in that church,” she said. “Not in the choir, because we were too young to have been in the choir. I started a young people’s group. There were about five of us. We did our own singing. What we did at that time would be called contemporary, compared to what the choir was doing.

“As long as I was in the church, I was held to very strict rules. After my mother passed away, I was about 17 years old. And then I got with another gospel group,” she said. “From that gospel group, we were heard from someone else, by Professor Charles Taylor. He was a gospel singer/pianist. And he went into the Apollo Theatre, and he asked us to join him, me and the group that I was with. I was with two other girls. So that was my first experience going into the Apollo, as a gospel singer. And I was on a bill with Sam Cooke, Lou Rawls–because he was with the Pilgrim Travelers–and the Caravans. All of the big singers, and I was on that show with them.

“Time passed, and I figured, ‘Well, that’s it! I had my little Apollo Theatre!’ So eventually, one of the male quartet groups that were always making the different programs and shows with us, they needed a tenor. And so they had trouble finding guys, and so one of them spotted me one day and said, ‘What if we train you to sing the baritone part up, and then you can join us?’ ‘I don’t know anything about rock and roll. I don’t know how to sing rock and roll, only gospel.’ They said, ‘We’ll teach you.’ They did. We called ourselves the Manhattans. The Manhattans is not the same Manhattans as we know today. We just happened to have had that name.”

Manhattans bass singer Freddy Johnson issued Maxine a challenge one auspicious day that inadvertently led to her first smash. “One day I’m sitting there, and I’m angry at the world. You know that whole syndrome? Not the world, but at certain men. I’m sitting there steaming. The reason I was steaming, the leader of the group said, ‘You never donate anything to the group. Here, here’s a title. Go write something!’ And so that’s why I was sitting there steaming. How dare he just throw this title at me? So I’m thinking about all my past experiences in the short span that I was out there, and all of a sudden this melody came to me, and the words just started coming, and in about ten minutes I was through! And I wrote the song, and I presented it one day in rehearsal, and they said, ‘Okay.’ They just wanted to know whether I did it or not. No one flipped over it, nothing. So I just put it away until two years later.”

The little ditty that Maxine scribed was entitled “All In My Mind.”

Before long, the Manhattans went their separate ways. “A lot of the guys after awhile got drafted into the service, and so that broke up the group,” said Maxine. “So we split up, and there was about three of us left. We called ourselves the Treys for a quick minute.” That group also reportedly included Sammy Turner of “Lavender Blue” fame and Julius “Mack Starr” McMichael of the Paragons. Brown wasn’t fated to sing with a vocal group of any sort for long.

“I went one day to hear a friend of mine sing in Queens. And he called me up to do a number. I got up and did ‘Misty.’ And I’d never sung with a live band before! So the guy who booked the club came over to me and said, ‘Hmmm, you sound pretty good! Are you interested in working here?’” said Brown of her future manager and husband, Mal Williams. “He had another act at that time by the name of Inez & Charlie Foxx. He lost them in some sort of dispute. So the next thing you knew, he looked to me. He asked me to go in the studio.

“We were looking for material, so he said, ‘Don’t you have anything?’ I said, ‘No!’ He kept pestering me for some songs, some original songs. I said, ‘Okay, the only thing I have is when I wrote with this group, the Manhattans.’ I had this old song. It was ‘All In My Mind.’ And he said, ‘Well, this is better than the stuff we’re going in the studio with.’ And we went in and recorded that. Really, the flip side was supposed to be the A-side. But it turned out ‘All In My Mind’ was. And that demo, as we made it, is still the same demo today. That was the beginning of my career in rhythm and blues.”

Leroy Kirkland, a longtime fixture on the New York studio circuit, was the musical director on the date, held at Adelphi Studios in the basement of fabled 1650 Broadway in midtown Manhattan. Brown doubled on piano for the track. “Since I wrote it, I played it,” she said. “Jimmy Spruill was the guitar player. And he had one of those long guitar cords, because he was a gimmick guitarist. So he would look over my shoulder and tell the band what I was playing, ‘cause we had no charts or anything. So he told them what I was playing. I was playing the piano, but I wasn’t singing it. So we made the track, and I got up and sang to the track. The only thing that Tony Bruno did was to remove me from the track and put on a real piano player.”

Bruno came into the equation after the session was complete. “Mal Williams took it around to all of the major labels. And at that time, girls were not happening so much. So one day we’re standing in front of the Brill Building, and Tony Bruno walked out and said, ‘Hey Mal, what have you got?’ He said, ‘I’ve got this demo and her!’ So he said, ‘Well, bring it up and let me hear it!’ So the next day he took it up and let him hear it, and he flipped! Especially he flipped out over the trombone part. The next thing you know, he grabbed the record and put it out.” “All In My Mind” came out on Bruno’s tiny Nomar label and took off, blasting up to #2 R&B and #19 pop on Billboard’s charts in early 1961.

“We were shocked. Definitely shocked and unprepared,” said Maxine. “Because you want to be in the business, and you try and you try, but it happened so fast it caught us unaware, believe me. I think it broke sometime around September, and the next thing you know, I’m making my debut at the Apollo Theatre at Christmas. Here I am back on the Apollo stage, and this time as a solo. All I remember going onstage is somebody gently put their hands in my back and pushed! That’s how I got out onstage.”

There was no sophomore jinx in Brown’s immediate future. “By this time, things were happening so fast for me,” she said. “Now I need a guitar player, ‘cause we’re traveling on the road. Right from the Apollo Theatre came the Howard Theater in Washington. And then Chicago, the Regal Theater. Baltimore, the Royal Theater. So we were making that whole tour. And I needed a guitar player to conduct for me. And I got this young man by the name of Sammy Taylor. He was the brother, believe it or not, of the Rev. Charles Taylor, who had hired me the first time. Anyway, he played guitar. He was a blues singer, and he was getting ready to record for himself. And when he played that song for me, I said, ‘I’ve got to have it! That’s my next hit!’ And sure enough it was.” Taylor would make some soul stunners of his own for Enjoy, Atlantic, and Capitol, but none of them equaled the success of Maxine’s rendition of his “Funny,” which sailed to ##3 R&B and #25 pop that spring.

The love affair between Maxine, Mal, and Nomar was short-lived. “You know when you go to your distributor for your first money and what have you? Well, they were not going to pay off. This is where the trouble came. So they weren’t paying the record company. The record company couldn’t pay me,” said Maxine. “Mal Williams said that rather than be a one-record hit artist, it would be best if we left. And Tony agreed too, because his hands were tied. We only left one song in the can. And the only thing Nomar had to release after we left was a song called ‘Heaven In Your Arms.’ That’s all we had in the can. And he put ‘Maxine’s Place’ on the flip side. It was an instrumental. Then we were shopping, and we went straight over to ABC-Paramount.”

The major label was making a real push into the R&B field thanks to Lloyd Price, Ray Charles, and B.B. King. Unfortunately, their sales figures weren’t matched at ABC by Maxine, despite the firm rapidly issuing eight of her singles including the rampaging Curtis Mayfield composition “I Don’t Need You No More” as half of the first (Williams had more luck helming the Impressions’ ‘61 smash “Gypsy Woman” for ABC). “We recorded a lot of stuff over there, but apparently nothing happened because we had hit the era of the payola, so nothing was really happening then,” said Brown. “We tried to promote it, and it wasn’t happening.” Mal kept his protégé on a heavy ballad diet at ABC; Bobby Stevenson penned her encore “After All We’ve Been Through,” and Maxine’s third outing on the label, “What I Don’t Know (Won’t Hurt Me),” mined much the same torchy territory.

Maxine’s chart drought came to a welcome halt in 1963 when Scepter Records boss Florence Greenberg took note of her plight. “One day I ran into Florence Greenberg in a restaurant at the corner of where 1650 is. And she says, ‘When are you going to leave that label and come over to my label and let me do something for you?’ I said, ‘If you want me, go get me!’ And the very next day she did. She went over to ABC-Paramount and bought everything that they had. Her reason was–it was sensible–she didn’t want Paramount releasing it if she happened to have gotten the hit with it.” Much as RCA Victor had done when it acquired Elvis from Sun Records, Greenberg snapped up Maxine’s ABC masters, reissuing many of them on Brown’s debut album for Scepter’s sister imprint Wand.

Bruno returned to Maxine’s support squad as producer of her first Wand single, “Ask Me.” “We were not angry, you know what I mean?” said Brown. “He was still involved, and he and his wife Brenda wrote that.” The same pair penned its equally exhilarating flip, “Yesterday’s Kisses.” The dramatic, violin-enriched “Ask Me” rose to #75 pop during the spring of ’63, restoring Brown’s momentum. For her encore “Coming Back To You,” Greenberg enlisted Ed Townsend, whose deep-voiced croon made “For Your Love” a 1958 smash, as her new producer (he wrote the number with Sam Cooke’s business partner and former Pilgrim Travelers mainstay J.W. Alexander). The stately “Coming Back To You” only managed a #99 pop showing in early ’64; perhaps Wand should have pushed its ebullient flip “Since I Found You” instead.

“When Florence called Ed Townsend in to be a producer over to the label, it was my turn coming up next. And so he kept saying, ‘We almost have the songs ready, but there’s this one song running through my mind, and I can’t finish it. Come on, we’re going to finish writing that song!’ He refused to go on with the session until we completed that song. That’s how we got to write together ‘Since I Found You,’” she said. “It’s a nice little blues bounce thing there.”

Luther Dixon, the mastermind behind the Scepter/Wand winning streaks of the Shirelles, Tommy Hunt, and Chuck Jackson, picked up the production reins for Brown’s next offering, the storming “Little Girl Lost” (Luther wrote it with R&B shouter Titus Turner and former Four Buddies member Larry Harrison). “I just think the groove was wrong on it. It could have been a cute song,” she said. “It was a little too fast for me, but it was pretty good.” The fiery Reggie Obrecht-penned “You Upset My Soul” adorned the B-side.

Though it was unrelated to the Supremes’ song of the same title, “Put Yourself In My Place,” Maxine’s next elegant Wand ballad outing, did share one characteristic with Motown’s standard operating procedure: interchangeable backing tracks. “I did it first,” she said. “You know how the different companies used different people on different tracks, right? Later on, they had Big Maybelle to come in and to sing in my key on my track. They shared the tracks with her.” Bruno was back as arranger; Florence’s son, Stanley Greenberg (professionally billed as Stan Green), had taken over as Maxine’s producer.

On the flip sat a sophisticated Burt Bacharach/Hal David ballad, “I Cry Alone” (they were in the midst of an incredible creative run with Dionne Warwick on Wand). “We went into the studio at eight a.m. to do the song. I could not believe I was hitting those notes. It was Dionne Warwick’s track. It was a song that Burt had scrapped with her. And Stan liked that one. I think if I’d stayed there much longer and they’d given Stan more leeway, I think he would have been my Burt Bacharach, to tell you the truth. Because he heard things for me. What a genius. What a beautiful man he was.” Green’s sightlessness proved no problem behind the board. “It didn’t matter,” said Maxine. “He knew his way around the studio.”

Stan’s mother treated her artists like family. “As a businesswoman,” said Brown, “I think she held her own pretty good. As far as personally, she was the sweetest person you’d ever want to know. Especially, she loved I call it her stable of kids. That was the Shirelles, Dionne Warwick, Chuck Jackson, Tommy Hunt, myself, and for a short moment, the Isley Brothers. We were her kids. She would not let anybody harm us. She was like a mother hen with all of us. But she was a tough businesswoman.”

Another of Green’s reclamation projects, the irresistible Gerry Goffin/Carole King composition “Oh No Not My Baby,” proved Maxine’s top Wand seller, maxing out at #24 pop in late ‘64/early ’65 (Bert Keyes handled the arranging duties this time). “Originally, that track was done by the Shirelles,” said Brown. “They were at that point in their career where they wanted more voices to be heard, so they were all doing the lead on this, and it was impossible to figure out the melody. So Stan Green said, ‘I think I’ve got your next hit for you! Go home and study it, and pick out the melody out of all of these voices, and then come back when you’re ready.’

“I took the record home. I didn’t pay too much attention. And I put it on a boom box and put it in my window and I sat on the porch. And these two girls were skipping rope, and as the record played, they kept saying, ‘Oh no, not my baby.’ I said, ‘Uh-oh! When people start singing the hook, you’ve got something!’ So I went back in the house, and I went to work. But Stan Green picked that one.” Dee Dee Warwick harmonizes with Maxine on the classic platter, the Sweet Inspirations providing the rest of the track’s delicious vocal backing. Dixon helmed the highly danceable opposite side, “You Upset My Soul.”

“They were putting the records out like a factory,” said Maxine. “They didn’t give you enough time to study it, and come up with any creative juices. A lot of songs came through that were very nice, but unfairly treated because of the rush. You learn it yesterday, you do it today. And I didn’t think that was right. And a lot of good songs got lost in the shuffle because they weren’t analyzed enough to give it the right treatment that it deserved. I think ‘You Upset My Soul’ was one of them, because it’s a good song, but sometimes you have to play with it and see if you’re in the right groove.”

Goffin and King also supplied the plug side on Brown’s next enchanting Wand offering, “It’s Gonna Be Alright,” which made it to #26 on Billboard’s revitalized R&B charts and #56 pop in the early months of ’65. “That was specifically for me,” Brown noted of the uptown soul gem’s origins.

Wand teamed Maxine with its top male singer, Chuck Jackson, to pump out even more hits. Their first duet release, a slow-grind revival of New Orleans singer Chris Kenner’s Popeye-friendly “Something You Got,” proved a far bigger hit than its predecessor, rising to #10 R&B/#55 pop during the spring of ‘65.

“Chuck Jackson wanted to produce his own things. And that was his band on ‘Something You Got,’” said Maxine. “That was his road band. And he wanted to convince Florence that he could produce. So he was using these songs to help him get his point over. And then he played all of the things for Florence. And I happened to come into the studio that day, up into the office. And he was trying to convince her. Apparently she had already heard it. She said, ‘Oh, it’s nice, but I’ve heard it before. Why don’t you try something–oh, there’s Maxine. Go get her and try something with her!’ That’s how Florence operated. It’s never a well-thought out plan. It can just be something on the spur of the moment.” The attractive pair followed it up with a Paul Griffin-arranged “Can’t Let You Out Of My Sight” and then a rendition of “I Need You So,” a classic Ivory Joe Hunter ballad harking back to 1950, both nicking the bottom end of the pop charts.

Always a shrewd judge of talent, Greenberg recruited the young writing trio of Nickolas Ashford, Valerie Simpson, and Joshie Jo Armstead to collaborate on material for her “kids,” Chuck and Maxine being no exception. Their “I’m Satisfied” suited the duo to a tee. “Chuck and I were both on the road working, but Ashford and Simpson were churning them out and sending it to us. And we’d come back home and we’d learn it, and we’d do it, and we’d hit the road again. But we did a lot of their material,” said Brown. “One of the songs that we recorded first was ‘Let’s Go Get Stoned.’ It didn’t become a big hit with us, but it was more of a hit with Ray Charles. We said, ‘At least he had good taste!’” Ronnie Milsap also waxed the ditty for Scepter.

Nick, Val, and Jo conjured up the slinky “One Step At A Time,” a #55 pop entry for a solo Maxine in mid-’65 with Green still behind the board, as well as half of her next inspiring offering, “You’re In Love.” “That’s them singing in the background,” noted Brown of the latter. The plug side of “You’re In Love” was a Green-helmed remake of James Ray’s “If You Gotta Make A Fool Of Somebody” that made a bit of pop noise late in the year. Brown’s Wand 45s were often uncommonly strong on both sides, making it hard for radio programmers to choose.

Rudy Clark, the composer of “If You Gotta Make A Fool Of Somebody,” tailored Maxine’s 1966 pounder “One In A Million” to Greenberg’s specifications. “We heard a song by Stevie Wonder called ‘Uptight.’ So Florence flipped out over that rhythm that they had, and she called Rudy Clark: ‘Write me something real quick!’” she said. “I was in Chicago, and we recorded ‘One In A Million.’ It’s in that good Motown kind of feeling. That’s the only time I’ve ever recorded in Chicago.” It was paired with Maxine’s own brassy pounder “Anything You Do Is Alright,” future pop crooner Steve Tyrell serving as her producer. Brown co-penned her next Wand release, the percolating “Let Me Give You My Lovin’,” with her latest producer, Tony Kaye (its arranger Leroy Glover went back to her ABC days). “That’s another one of those songs that was shipped in to me,” she said. A cover of the Beatles’ “We Can Work It Out” sat on the flip. The uplifting “I Don’t Need Anything” came next for Maxine, though like its two most recent predecessors, it failed to chart (its flip “The Secret Of Livin’” was similarly entrancing).

Far more successful from a commercial perspective was Maxine’s ongoing musical partnership with Jackson. Their fiery rendition of Sam & Dave’s “Hold On I’m Coming” was another winner, jumping to #20 R&B/#91 pop in early 1967. Jackson and his bandleader. Bobby Scott, were calling the shots in the studio, right down to the key that “Hold On” was arranged in. “I had to stand way back to hit it, way back from the microphone,” said Maxine. “They were his band and his tracks.” A revival of Shep & the Limelites’ touching ballad “Daddy’s Home” made a #46 R&B/#91 impression that spring for the duo, but their tandem hits didn’t translate into extended touring. “When Chuck and I had the hit, a lot of times it was too expensive for Chuck and I to work on the same show together,” she said. “So Chuck had his own band, and Yvonne Fair would do all my parts on the road with him.”

Saxophone master King Curtis’ sublime 1963 instrumental hit “Soul Serenade” acquired itself some sexy lyrics from Luther Dixon somewhere down the line. Maxine movingly sang them twice in 1967, first on a live album recorded in New York’s Central Park and then in the studio for a single that may not have even been released but clearly rated hitdom (Aretha Franklin also cut the tune for her first Atlantic album). A trip down south to work in the studio with the immortal Otis Redding remained similarly unheard by her fans at the time.

“Florence had this idea, so she spoke to Otis,” said Brown. “They made the arrangements, and I went down to Muscle Shoals. And while I was down there, Otis showed me a couple of things that he had started on. But he had to go out and perform his own shows. So we would work a day with the band and with him, learning the melody and everything of the tunes. He said, ‘Now you stay here and work on it, and we’ll be back tomorrow.’ So they would fly out wherever their job was, come back the next day, and we would go to work. And as the musicians were coming into the studio, they said, ‘Man, you’ve got to do something about that raggedy plane! It’s gonna kill us one day!’ And sure enough, we were not through with it. I had to go back to New York.”

Tragically, Otis never made it back to Muscle Shoals to finish work on those masters, which included Redding’s pounding “Baby Cakes,” eventually rescued from the vaults by Ace Records in the U.K. “I just wish we had more time. And I wish I had lowered some of those keys. But they like you to be at the top of your range,” she said. Even though the session was shelved at the time, the Shoals experience was a good one for Maxine. “It’s a much freer atmosphere,” she said. “Everything in New York is controlled–musicians, conductors, and that whole thing. But down there, you just do it ‘til it gets right, until it feels good. And Otis was a free worker. That’s the way he was.”

With Greenberg’s promotional emphasis primarily focused on Dionne Warwick and B.J. Thomas, Brown exited Wand in 1968. “Things were beginning to die down. The Shirelles, they had left. They had broken up,” said Maxine. “A lot of people were mumblin’ and grumblin’.

“A lot of us were going our own way. And I was just sitting there dying. So I needed to do something. So they released me. I asked for a release, and they released me. And I went over to Columbia/Epic.”

On the surface, Mike Terry, the baritone sax soloist on the Supremes’ early smashes as a Motown house musician before going his own way, would seem to have been an excellent choice to produce Brown. He helmed her Epic LP Out of Sight in Detroit, split about equally between originals and covers (including Bobby Hebb’s “Sunny,” Sam Cooke’s “Sugar Dumplin’,” and the Temptations’ “I Wish It Would Rain”). It spawned her Epic single “Seems You’ve Forsaken My Love,” written by Brothers of Soul Fred Bridges, Robert Eaton, and Richard Knight.

By the time Epic issued her next 45, an ominous “From Loving You,” she’d been placed in the hands of staff producer Ted Cooper, also credited as arranger on the Michael Gordon copyright. The move to Epic hadn’t gone as planned. “Well, it was no better there,” said Maxine. “You know, you can get signed with a company because they know who you are, but if you don’t have the right producer, again you get lost.”

Moving to the brand-new Commonwealth United label brought renewed commercial prosperity. Her first single there, the Rose Marie McCoy/Helen Miller-penned “We’ll Cry Together,” was a #15 R&B/#73 pop seller during the autumn of 1969, launching the imprint in style (Charles Koppelman shared production credit with Don Rubin and Philly denizen Bob Finiz). Her encore “I Can’t Get Along Without You” made a #44 R&B impression during the spring of ‘70. The label also pressed up a Brown album, Bert de Coteaux doing the arrangements, but it didn’t last for long. “The parent company failed, the movie company, and it collapsed the record company,” said Maxine.

So it was on to Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore’s Avco Embassy imprint in 1971, where Maxine wrapped her pipes around the sensuous “Make Love To Me,” written and produced by the prolific Van McCoy and Joe Cobb. They surrounded Maxine with lush strings and a choir, but it didn’t hit. Neither did 1972’s “Treat Me Like A Lady,” the funky work of writer/producers Tony Camillo and Perry Boyd (Camillo would helm Gladys Knight & the Pips’ across-the-board chart-topper “Midnight Train To Georgia”). The same pair was behind Maxine’s Detroit-cut “Picked Up, Packed And Put Away.” But Avco couldn’t get Maxine a hit. She was through.

“I had to look into the future. I said, ‘What’s happening here?’ I put myself in acting school and dancing school,” she said. “Because when I would go to auditions, they’d say, ‘Can you move?’ I’d say, ‘Oh, yeah, sure, sure.’ Then when they’d put the count in–5-6-7-8–and we’d start turning and bumping into each other, I said, ‘Uh-oh! We gotta fix this!’ So I went to take some jazz dancing lessons, and learned how to get with the program a little bit.” All that training paid off when Brown dazzled Broadway theatergoers during a year in the cast of the acclaimed musical Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope. “I loved it,” she said. “That was my first Broadway experience. It was wonderful.”

By the 1980s, Maxine had grown tired of show biz altogether. “Got disgusted. Fed up. Through,” she said. “Loved singing. I never a day hated singing. I just couldn’t take the business. Because after awhile, the business starts to leave you. Things were not happening. If you didn’t have a hit record–‘What have you done for me lately?’–then how can you work? So I had a horrible time trying to work. So I just said, ‘Well, that’s it.’ And then one day I said, ‘No, I’m not gonna!’ And some people said, ‘What are you doing? Why are you sitting there? Get up and do something!’ So I started writing again, and trying to get with the new program.”

Encouragement from a fellow R&B survivor helped rekindle Maxine’s desire to perform. “Ruth Brown, she was the cause, she’s the one who started setting the fire under me again,” she said. A recurring role in the sassy musical Wild Women Don’t Get The Blues kept Brown in the public eye, and when she reprised “Oh No Not My Baby” on PBS-TV’s R&B 40: A Soul Spectacular, it was obvious that Maxine’s soulful spirit hadn’t dimmed one bit.

“That was so great to do,” she said. “I was just delighted to have been on that show. You would think we were all back at the Apollo again. Everybody cheering the other one on! Oh, it was wonderful in that rehearsal. I mean, the spirits were high, because everyone’s singing, and everybody just remembering, and everybody’s in great shape and looked good. It was wonderful.”

Maxine Brown’s eagerly awaited Ponderosa Stomp appearance on Friday, October 4, 2013 is sure to be a wonderful, profoundly soulful experience as well.

–Bill Dahl

Source for Billboard chart positions:

Joel Whitburn’s Top R&B Singles 1942-1988, by Joel Whitburn (Menomonee Falls, WI: Record Research, Inc., 1988)