WRITTEN BY BILL DAHL

Extraordinary showmen were everywhere on the 1960s soul scene. Texas boasted more than its share. But Roy Head stood out from the pack no matter where he performed — and not just because he happened to be of the Caucasian persuasion. The blue-eyed Lone Star soul screamer tore up audiences of all colors with his outrageous gymnastics.

From the first horn blasts of his blistering 1965 smash “Treat Her Right,” Head’s feet flew like he was slipping on ice. Then he’d drop down into the splits. A few bars later, Roy would twist backwards like a human pretzel, balancing nearly on his cranium as his lithe body contorted in a sort of bizarre yoga maneuver that defied all notions of what the human physique is capable of. Especially while simultaneously singing.

Though he’s admittedly not quite that limber half a century later, Roy remains a master showman. “Still having a good time. Still doin’ flips and splits, still got all my hair, and I’m not potbellied,” reported the longtime Ponderosa Stomp favorite, who will be back for this year’s edition. “Still do the mic stand and the mic — you know, twist it all around me and throw it at the customers, and sometimes knocking one out. But that’s rare!”

Born Sept. 1, 1941, in Three Rivers, Texas, Roy soaked up all sorts of roots music genres while growing up in San Marcos. The R&B bug bit him the hardest, his early heroes including “Etta James, Bo Diddley, Jackie Wilson, naturally James Brown,” said Roy. “Joe Tex is the one that taught me all the mic stuff.” And it bit early.

“I started in 1956, singing on the school bus. About 1958, I put a little old band together. Thanks to Edra Pennington, who owned a funeral home in San Marcos, Texas, I put me a little band together, and we started playing little talent shows, etc. And we started winning. So we formed a group called Roy Head and the Traits in 1958.” At first a trio, the band was initially known as the Treys until a local deejay fortuitously mispronounced their name.

“TRAITS KIND OF FIT EVERYTHING”

“We couldn’t ever come up with a name, and Traits kind of fit everything,” said Head. “Everybody had different traits, so we just thought it’d be a good name.” When they first found their way into a recording studio, the Traits consisted of guitarists Tommy Bolton and George Frazier, pianist Dan Buie, bassist Bill Pennington (Edra’s son), and drummer Gerry Gibson (who would eventually become a member of Sly & the Family Stone).

Thanks to Edra’s efforts, Roy debuted on wax in mid-1959 with a thundering “One More Time” on Bob Tanner’s San Antonio-based TNT Records (previously home to rockers Johnny Olenn, Jimmy Dee, and Ray Campi as well as a then-unknown Bill Anderson). The single and all its TNT follow-ups were credited solely to the Traits. “She knew Mr. Tanner. And he liked what he saw,” said Head. “He said, ‘OK, we’ll give ’em a shot.’ So we came with ‘Baby Let Me Kiss You One More Time,’ which was a big regional hit.” A lowdown “Don’t Be Blue” graced the flip. The entire band was credited with penning both tunes, a democratic practice that would endure throughout their TNT tenure.

Before year’s end, the Traits encored on TNT with a rocking “Live It Up,” positioning the atmospheric teen ballad “Yes I Do” on the B-side. TNT clearly believed in the band, issuing the swaggering “My Baby’s Fine” and its ballad flip “Here I Am In Love Again” during the spring of 1960 (Roy’s pal B.J. Thomas revived the latter on the obscure Lori label long before he embraced stardom) and the happy “Summertime Love” later in the year (the swampy ballad “Your Turn To Cry” was its plattermate).

1961 brought another TNT single for the Traits, pairing the romping “Walking All Day” and the instrumental “Night Time Blues.” The Traits jumped ship to Jesse Schneider’s Renner label, another San Antonio concern, in ‘62 for a pair of 45s: The rumbling minor-key “Little Mama,” a Head/Buie composition, came backed with a faithful revival of Texas rocker Ray Sharpe’s signature slammer “Linda Lou”; while Roy’s self-penned “Woe Woe” was pressed up with a Tex-Mex-tinged remake of “Got My Mojo Working” as its zesty opposite side.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iDRSmPDJo3g

Young and fearless, the Traits held musical court inside some of the roughest watering holes on the Lone Star circuit. “We played places where they actually had chicken wire stretched across,” said Roy. “The kids liked to fight on the weekends. There’s nothing to do when you live in the country. It was pretty wide open in south Texas, and everybody would go to these dances on the weekend, they’d get a few beers in ‘em, and everybody would get in a scuffle. If you stopped, then it really got bad. So we just kept pickin’. And being outrageous.

“I even created a dance called ‘The Gator,’ which has been banned all over the country!” chortled Head.

“BACK THEN, THERE WEREN’T ANY GROUPS”

In their own neck of the woods, the Traits became a hot commodity. “At that time we were probably the biggest group,” said Head. “Because back then, there weren’t any groups. They were very few and far between. It was us and the Moods, and B.J. Thomas and the Triumphs weren’t even started. I started him singing. He used to come see me, and I’d introduce him as B.J. Thomas and the Zodiacs, out of Dallas. That was before he even started singing. He always said he had a sore throat, and he’d always hustle all the women. It was neat. One day I heard him sing. I said, ‘B.J., you need to get you a band together.’ Sure enough, he did. And after that, it was a tug of war.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=atuRht1NuaI&spfreload=10

Houston TV repairman Charlie Booth, producer of B.J.’s cover of “Here I Am In Love Again,” operated his own Golden Eagle logo, enjoying regional success in 1963 with blues guitarist Johnny Copeland’s “Down On Bending Knees.” Booth caught Head’s act and was impressed. “Charlie Booth came to see me play at a place called East Menard, Texas,” said Roy. “Riverside Hall. He saw me, and he liked what I was doing. He said, ‘I’d like to cut you.’”

Booth supervised a 1964 revival of Jimmy McCracklin’s sizzling “Get Back” for Lori, the tiny Houston firm billing the single as by “Roy – Sarah & the Traits” despite backup singer Sarah Fulcher’s vocal input being rather minimal. She was a tad more prominent on the flip “You’ll Never Make Me Blue,” penned by Traits saxist Danny Gomez.

Huey P. Meaux — the irrepressible “Crazy Cajun” whose sizable producing resume already included Gulf Coast-generated hits by Jivin’ Gene, Joe Barry, and Barbara Lynn — got involved in Head’s career right about when he signed with Back Beat Records, a subsidiary of Don Robey’s Duke/Peacock labels (the Houston label’s flagship artist was Bobby “Blue” Bland; other notables on its huge talent roster included Junior Parker, Joe Hinton, Buddy Ace, Al “TNT” Braggs, and O.V. Wright). “Charlie Booth and Huey Meaux knew Don Robey,” said Roy.

“I DID ALL BLACK MUSIC THEN”

First out of the box in 1964 on Back Beat was a rip-roaring remake of Big Joe Turner’s ’57 Atlantic release “Teen-Age Letter.” “I used to love Joe Turner,” said Roy. “I did a lot of things by Joe Turner. I did all black music back then.” The anguished flip “Pain” was an exception to that policy; though Back Beat credited Head as its writer, it was an adaptation of Lonnie Mack’s minor-key moaner “Why.” Head finally received front-billing on the 45, pressed up as by Roy Head and the Traits.

“Treat Her Right,” Head’s Back Beat encore, started out with the unlikely title of “Talking About A Cow.” “My bass player, Gene Kurtz, at the time, said, ‘Look, make this about a girl. Get out of the country and we might sell some records!’” said Roy. “We went in the studio, Gold Star Recording Studio over on Brock. For $500 we cut ‘Treat Her Right.’”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1GcOMAG0w5Q

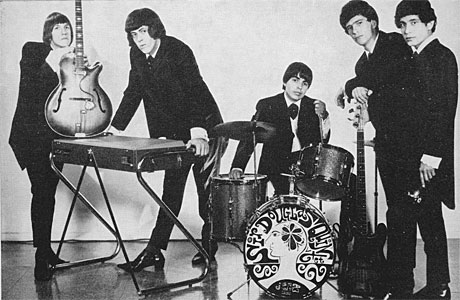

Other than Gibson on drums, the Traits, now based in Houston, had turned over almost entirely from the TNT days. Kurtz was reportedly joined by guitarists Johnny Clark and Frank Miller, trumpeter Dickie Martin, and tenor saxist Doug Shertz, though a promo photo from the period shows Tommy May on tenor sax and trumpeter Ronnie Barton (perhaps they replaced Martin and Shertz a bit later). “Charlie Booth really was the one that laid the record down in the studio,” he added. “Then we took it to Huey. Huey liked it. Huey naturally was the engineer on it. He shopped it to Don Robey and Don Robey bought it. The rest is history.”

“EVERYBODY FOUND OUT I WAS WHITE”

Apparently Robey envisioned “Treat Her Right” as little more than an R&B contender despite its irresistible sawing horn line, ultra-dynamic rhythmic churn, and Roy’s hair-raising vocal. “Don wouldn’t ever let me go on television nationally for a long time, ’til the record was already No. 1 on KHJ. I think that’s in L.A. When it hit No. 1 there, then he put me on national TV,” said Roy. “It was a Catch-22 for me. I was just kind of caught in the middle.”

Once “Treat Her Right” embarked on its rocket ride to No. 2 on both the R&B and pop hit parades during the autumn of 1965 (“So Long, My Love,” a rather generic ballad, sat on the B-side), Robey was in total favor of Roy unleashing his contortionist antics on “Shindig!,” “Where The Action Is,” “American Bandstand,” “Shivaree,” and seemingly every other rock-and-roll-oriented national TV show (check out the astonishing “Treat Her Right” clips gracing YouTube for proof positive there). Roy also toured the East Coast theater circuit and nightclubs through the Midwest, winning over skeptical African-American audiences at each and every stop.

“I did the Roostertail in Detroit, I did the Apollo, I’ve done Phelps Lounge in Detroit, I did the Regal Theater. I did ’em all,” said Head. “I remember coming on stage at the Apollo Theater, man. I was working with the Joe Scott band. People were going, ‘Yeaahh!!’ I walked out and it was (silence). God, I thought, ‘What the hell?!?’ I mean, just night and day. But when I did the first few flips and some of the mic stuff, hell, they were up in the seats screaming. It was pretty neat, really.”

Ironically, all those riveting TV appearances meant Roy’s days as an R&B chart threat were history. “Once everybody found out I was white, then it just kind of … I don’t guess it was the same,” he said. “You know, like you hear somebody’s voice, and then you see ’em — it’s just, ‘God, I can’t believe that!’”

For a followup, Head dug into a blues-shuffle groove to pen the surging “Apple Of My Eye,” the Traits dispensing with horns altogether. “Gene Kurtz and I put that together. Of course, you can’t tell there’s any Jimmy Reed in it,” he laughed. “Everybody was doing everybody back then. Just get you a melody and throw different words on it, and change the beat.” The single failed to crack the pop Top 30, no doubt disappointing Duke/Peacock’s big boss man. “Don Robey was great,” said Roy. “He could hit a spittoon from 20 feet and never even leave a trace!” A female backing chorus graced the propulsive Kurtz-penned B-side, “I Pass The Day.”

Meanwhile, the enterprising Meaux sold a cache of Head tapes to Florence Greenberg’s New York-based Scepter Records that sounded indistinguishable from his Back Beat output. Greenberg cobbled together an album from her master purchase that she slyly titled “Treat Me Right” (Robey never did spring for an LP to capitalize on Head’s smash, leaving the door wide open for such East Coast chicanery), sporting no mention of the Traits. What’s more, its title track was a retitled “You’ll Never Make Me Blue,” Sarah’s contribution going unrecognized. Scepter ended up with two chart entries out of the deal: Roy’s supercharged treatment of Rosco Gordon’s “Just A Little Bit” cracked the pop Top 40 during the fall of ’65 with “Treat Me Right” its plattermate, and “Get Back” was resurrected for a low-end chart appearance in early 1966.

“TOO MUCH FANCY STUFF GOIN'”

Proudly wearing his R&B roots on his sleeve at Back Beat, Head and the now-hornless Traits attacked harp genius Little Walter’s Willie Dixon-penned romp “My Babe,” but their grinding early ’66 revival barely nicked the pop hit parade. Though Kurtz received label credit as its arranger and conductor, the Traits were no longer co-billed on Roy’s incendiary spring ’66 release “Wigglin’ And Gigglin’,” which reinstated the punchy horn section. The group’s name would no longer appear on Roy’s Back Beat output.

“‘Wigglin’’ And Gigglin’” didn’t do a whole lot,” noted Roy. “It was more mulatto than it was black, if you can understand what I’m saying. It just had too much fancy stuff goin’. It just didn’t stay with that power-drivin’ thing.” There was plenty of drive to its plattermate, a faithful rendition of Roosevelt Sykes’ often-covered “Driving Wheel” closely modeled on Duke labelmate Junior Parker’s 1961 hit rendition.

Head played Chicago’s Regal Theater in July of 1966 on a star-studded bill headed by Chuck Jackson and Gladys Knight & the Pips. One attendee remembers Roy backing offstage in mid-song due to a wardrobe malfunction: He was forced to tie his jacket around his waist after splitting his tight trousers wide open in the rear. “That was a pretty frequent occurrence back then because they didn’t have the stretch jeans and stuff,” chuckled Roy. “The clothes were kind of molded to look good onstage. That hasn’t happened since they came in with stretch.”

“ZZ TOP, THAT’S WHERE THEY GOT ‘TUSH’ FROM”

Back Beat’s braintrust reached across the Atlantic for Roy’s next A-side that fall. “To Make A Big Man Cry” had been introduced over there by Tom Jones, but when it came to macho, Tom had nothing on our man Roy. “I got a demo on that from Tom Jones, believe it or not,” said Head. “He was doing the vocal on it. We did that really as a filler. If I’d just taken the time to put the thing together right, that could have possibly been a good song.” Actually, Back Beat added a string section to the sophisticated ballad in a concentrated bid for pop airplay, but it barely charted. Once again the label’s own publishing catalog was raided for the opposite side of the single, a relentless revival of Bobby “Blue” Bland’s ’61 smash “Don’t Cry No More.”

By the beginning of 1967, Roy was investigating Lone Star garage rock with his savage Bo Diddley-beat “You’re (Almost) Tuff,” loaded with twangy, multilayered guitars that throbbed with intensity. “Gene Kurtz did ‘You’re (Almost) Tuff,’” noted Head, claiming, “ZZ Top, that’s where they got ‘Tush’ from. They had an article in ‘Rolling Stone where they got the idea from ‘You’re (Almost) Tuff.’ That’s how they came up with ‘Tush.’” Its instrumental B-side was titled “Tush Hog” and credited to the Roy Head Trio; Kurtz and Gibson were listed as two of its composers, but it was really a note-for-note cover of a Freddy King instrumental.

Roy bid adieu to Back Beat that spring with a swaggering “A Good Man Is Hard To Find.” Longtime Meaux associate Leo O’Neil scribed its surging B-side, “Nobody But Me (Tells My Eagle When To Fly).” “Leo O’Neil arranged that,” said Roy. “Great trombone player. He arranged a lot of things. ‘A Good Man Is Hard To Find,’ he put all of those together. He was one of the best ’bone players in Houston.”

Left behind in the vaults was an incredible revival of John Lee Hooker’s “Boogie Chillen” that moved the storyline from Detroit’s Hastings Street to West Hollywood’s Sunset Strip, Roy fancifully encountering James Brown, Otis Redding, Jackie Wilson, and the Animals at the Whisky a Go Go. The storming, guitar-dominated arrangement really did anticipate ZZ Top’s boogie-fired sound (the performance belatedly surfaced on Varese Sarabande’s 1995 CD compilation “Treat Her Right: The Best Of Roy Head”). Another unreleased Back Beat gem, the brass-leavened “When I Marry Sunshine,” also debuted on the disc.

The Traits were long gone by this time. “My group sued me for six-sevenths of everything I made, because they didn’t want to travel. I had all these tours offered and all this, and they all had different occupations. Some were going to college to be doctors and lawyers. So we signed a little peace bond with each other. If anybody wanted to walk, they could. And then, whenever the walking started, there wasn’t any road to walk. They all sued me.

“So I just quit singing for about a year. Which was really — well, you can tell I’m country. It wasn’t real sharp. If I’d have had the snap, I’d have went on and sang, gave ’em the money and went through the wade with ’em, and probably had a different road.”

Head rebounded by signing with Mercury Records, which sent him to Chips Moman’s American Studio in Memphis in the autumn of 1967 (A&R man Boo Frazier was technically in charge). For the first time Head’s country leanings emerged as he tore through Mickey Newbury’s tongue-twisting “Got Down On Saturday (Sunday In the Rain),” though horns did jump in at the end. It was chosen as half of his first 45 for the label, along with Wayne Carson Thompson’s steamy opus “Then The Grass Was Green.”

Moman had been elevated to official producer status when Head reverted to his wicked soulful ways on his blazing 1968 Mercury encore “Broadway Walk.” The original version had also been cut at American by Bobby Womack, who wrote it with Darryl Carter, Dan Penn, and Spooner Oldham. “He could just scream a little more than me,” laughed Roy, whose horn-slathered rendition was just as strong. Carter teamed with Mark James (poised to crash the big time by scribing Elvis’ juggernaut “Suspicious Minds”) and David Bevis to create the tasty flip “Turn Out The Lights.”

Doug Sahm and his Sir Douglas Quintet had given Meaux one of his greatest successes as a producer in 1965 with their Tex-Mex groover “She’s About A Mover” for his Tribe imprint. The Lone Star rocker subsequently fled the state of his birth in favor of free and easy San Francisco; he and a reformed SDQ backed Roy in July of ’68 for his next Mercury platter there. Sahm wrote, produced, and arranged the pulsating “Ain’t Goin’ Down Right” and a grinding “Lovin’ Man On Your Hands,” the latter sporting some very spacy horn interjections. A couple of months later, with invaluable keyboardist Augie Meyers back in the SDQ fold (he’ll be performing at this year’s Stomp), Sahm waxed the immortal “Mendocino.”

The Sahm/Head experiment lasted for only one single. Mercury brought the singer to its Chicago headquarters for his last session on the label in March of 1969. Soul A&R man Jack Daniels produced; he’d had success working with blues harpist Junior Wells for Mercury’s Blue Rock subsidiary. Collaborating with his frequent writing partner, Windy City soul singer Johnny Moore, Daniels gave Roy their “I Miss You Baby” and “I Want Some Action.” Jack also helmed Head’s Mercury farewell at the same date, pairing a second crack at “You’re Tuff Enough” with a revival of “Dr. Feelgood” that was presumably Piano Red’s song and not Aretha’s.

“WE’D CHOKE EACH OTHER TO DEATH”

Meaux resurfaced in Roy’s life right after that. “Me and Huey were off and on all through the years,” said Head. “We’d choke each other to death and get up and go drink a beer. Somehow we’d always do another project.” “Same People,” the 1970 album that Meaux produced on Roy and leased to ABC-Dunhill, was an extremely consistent piece of work: blue-eyed Texas soul with skin-tight horns and a tough rhythm section that brought out the very best in Head’s pipes.

“Huey Meaux was great,” said Roy. “‘Lil’ brother, you know I wouldn’t cheat you, lil’ brother!’ He was wonderful. Huey Meaux was a great guy. Always persistent. That’s what made Huey so good. He just didn’t take no for an answer.”

Only one single was culled from the set, coupling the insistent “Mama Mama” and a heartfelt revival of T.K. Hulin’s swamp-pop classic “I’m Not A Fool Anymore.” But the LP also boasted a funkier take on “She’s About A Mover,” the Cliff and Ed Thomas/Bob McRee-penned “Double Your Satisfaction” and “Trying To Reach My Goal,” and Head’s sweaty versions of Dyke & the Blazers’ “Let A Woman Be A Woman” and Jimmy Hughes’ “Neighbor, Neighbor.” Alton Valier supplied the stomping title track.

“I’VE ALWAYS HAD A THING FOR THE BEAT”

Best of all was “Soul Train,” an unstoppable update of Jackie Paine’s “Go Go Train,” a clever piece of material that the Crazy Cajun co-wrote with Valier and produced for his Jet Stream logo in 1966. Most of the soul stars of the day received playful name checks (Head and Meaux got mentioned on Paine’s original), and so it was on “Soul Train.” Jimmy Reed was the bartender on the train and Chuck Berry did the booking, but Rufus Thomas was unwelcome — he had too many dogs! Amazingly, Dunhill didn’t see fit to release “Soul Train” as a single.

“Problem with record labels,” said Roy, “you have so many people sitting behind desks that pick your hits for you that aren’t even entertainers. That’s the amazing part of the business. That’s one I never have understood. I just go in and cut songs that I love. I’ve always had a thing for the beat. If it doesn’t have a good, solid rhythm, then, you know.”

“COUNTRY’S VERY EASY TO SING”

Head needed a hit, so he enlisted the expert help of producer Steve Cropper, the revered guitarist for Booker T. & the MGs. Roy’s boisterous “Puff Of Smoke,” penned by Cropper and soul singer Sir Mack Rice, was the first single released on Memphis-based TMI Records, a logo associated with Trans Maximus Studios in the Bluff City that boasted distribution by CBS. “Puff Of Smoke” did the trick for Head, squeaking onto the bottom rungs of the pop hit parade during the summer of 1971 (the same pair brought in the flip, “Lord Take A Bow”).

A series of Cropper-helmed TMI followups brought Roy into 1973 without equaling the success of his TMI debut. It was clearly time for a change in career direction, and Roy decided to transform himself into a country music star. Why country? “Because I was hungry,” he replied. “Country’s easy to sing. A lot of people would probably say that’s a shit statement, but country’s very easy to sing. I grew up around country. It’s kind of a second nature to me.”

The strategy worked to perfection. While he never cracked the C&W Top 10, Head posted two dozen country chart entries between 1974 and 1985, beginning with “Baby’s Not Home” on the Mega label. “The Most Wanted Woman In Town” (its co-writer Royce Porter will perform at this year’s Stomp) went Top 20 on the Shannon imprint in ’75, and a hookup with ABC/Dot in 1976 brought Roy a sizable hit with “The Door I Used To Close.” “Come To Me,” again on ABC/Dot, was his biggest C&W seller of all toward the end of ’77, though its immediate followup, “Now You See ‘Em, Now You Don’t,” fared nearly as well on ABC proper from a commercial standpoint.

“THEN I’D ROCK THEIR ASS”

After he split ABC, Head scored more C&W chart items for labels both large and small: Elektra, Churchill, NSD, Avion, Texas Crude. But after more than a decade of success, the idiom’s charm began to wear a bit thin. “When all the youth movement came in with country, kind of like the psychedelic did with blues, I just had to go back to doing variety,” he said. “The blues eventually got a hold of me. I’d go up, do my country hits, and then I’d rock their ass. I rocked myself right out of that.”

Roy has been rocking houses ever since. He’ll be back this year to tear the Stomp up once again with his showstopping, mic-twirling antics. It’s been a full half century since he exploded on the national scene with “Treat Her Right,” and Roy Head shows no signs of letting up whatsoever.

“I loved every minute,” he said of his astonishing career. “I wouldn’t change nothin’.”

For more information on the 2015 Ponderosa Stomp and to purchase tickets, click here.