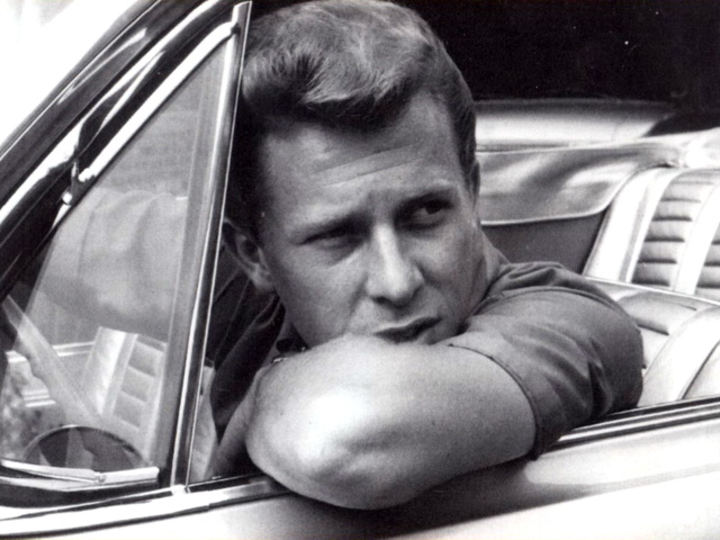

Darrell McCall arrived in Nashville from Ohio in 1958 along with his childhood pal Johnny Paycheck, then still known as Donny Young. Like Paycheck, McCall lent his flawless country vocal harmonies (and bass playing) to Lone Star State sons Ray Price and George Jones as well as Louisiana luminary Faron Young. After a brief foray into rock ’n’ roll with the Benny Joy-penned “Call The Zoo,” Darrell commenced a tour-de-force of honky-tonk brilliance that included standouts such as “This Old Heart,” “Excuse Me (I Think I Have A Heartache)” and “Fallen Angel,” singing the theme song for the countrified cinematic masterpiece Hud in 1963 and appearing in the low budget milestone, Nashville Rebel, alongside Waylon Jennings in 1965.

—

When you sing harmony as flawlessly as Darrell McCall has over the years for the cream of the country crop—Faron Young, Ray Price, Carl Smith—your own accomplishments are occasionally overlooked.

But Darrell’s personal musical legacy is as vast as the Texas landscape that he’s called home since 1970 (with a couple of relocations back to Nashville scattered in here and there). He appears Saturday evening on the Ponderosa Stomp’s Texas Honky Tonk Revue with Frankie Miller and James “Slim” Hand, and he’s long been a country luminary in his own right.

OHIO ROOTS

The Darrell McCall story doesn’t commence in the Lone Star State, however. He was born in New Jasper, Ohio, although you’d never know it from his music. “My dad traded a sow for an old guitar,” says Darrell. “I was about eight years old, I guess. He would sit around and sing a song every once in a while. It got me really into it, and I started learning to play some chords and singing.” Don’t be fooled by the geography; McCall heard country music greats aplenty as he grew up. “We had a lot of Hank Williams, and of course, Jimmie Rodgers,” he says. “Webb Pierce and Faron and people like that came along a little later, but I was listening to people like Hank Thompson and Merle Travis and Bob Wills.”

McCall got his start as a local deejay over WSRW, 1590 on the AM dial. “That happened kind of accidentally,” he says. “A bunch of people came to town and started a little radio station in Hillsboro, and there was nobody that had any microphone experience except the chief of police, Willard Parr. So they got him to start being a disc jockey there at the station. Then of course, I’d been singing on some mics. They said, ‘Hey, would you like to have a little program too?’ So I started having a little program on a Saturday. I wasn’t really into being a disc jockey too much. I wanted to sing.”

OFF TO NASHVILLE

And so he did—in partnership with another future star who then went by the name of Donny Young. “We became friends in something like 1957,” says Darrell. “We started singing together and writing together, and it just worked out perfect. He had been to Nashville before, and had recorded a song on Decca Records. He said, ‘Hey, let’s go to Nashville and record! We’ll go in as a brother act!’ So we changed our names to Young—Darrell and Donny Young, the Young Brothers. And we thought we were just going to tear Nashville apart.

“I was painting houses and barns at the time, and I got me a paycheck, and I went and bought us a couple of bus tickets to Nashville. Of course, we didn’t know a soul. Donny had known a few people, like Buddy Killen and Faron, and that was about it. So we came into town as a brother act, the Young brothers. And we just could not get started. There were so many brother acts—there were the Louvin Brothers, the Wilburn Brothers, the McCormick Brothers, the Stanley Brothers. They just didn’t need another brother act. So we had to split up.

“I think that’s the best thing that ever happened to us. We both went in separate directions, and I grew up as a musician in Nashville and a harmony singer, singing harmony with almost everyone because there were no harmony singers in Nashville except Roger Miller and myself and Donny Young. So we got all the harmony sessions, from George Jones to Faron to Ray Price to everybody else, (including) Frankie Miller.” Donny Young changed his name to Johnny Paycheck in the mid-‘60s and achieved his own prolonged bout with country music stardom (and the trials and tribulations that sometimes come with it).

HARMONY SINGER EXTRAORDINAIRE

Opportunities for the solo McCall to gain onstage experience quickly arose. “I went on the road to begin with with Audrey Williams,” he says. “That was Hank Williams’s wife. After he passed away, she picked up the band, the boys that Hank had like Don Helms, Sam Pruett, people like this, and started her own band. Buddy Spicher, the fiddle player, said she needed a bass player, so he said, ‘She’ll hire you just because you’re young!’ So that’s basically what I did. I borrowed a bass from a guy named Hillous Butrum in Nashville, and I started playing bass with Audrey. And that’s basically how I started as a band member.” Had he ever played a bass before? “No, but I had to learn real quick because it got real hungry!” laughs Darrell. “Audrey was really nice. She was good to us and treated us right. We had a lot of work, and that’s how I basically got started. That’s how I got to know Hank Jr. too. He was just a little boy. I think he was six or seven, something like that maybe.

McCall’s talent for clear, precise vocal harmonies fully emerged in 1960. “The first hit I was on was Freddie Hart with ‘The Key’s In The Mailbox,’” he says. “And I did a country album with George Jones on Starday—it was ‘Big Harlan Taylor,’ ‘Money To Burn,’ and all the heart songs: ‘Candy Hearts,’ ‘This Old Heart,’ all that kind of stuff. That’s how basically I got started.”

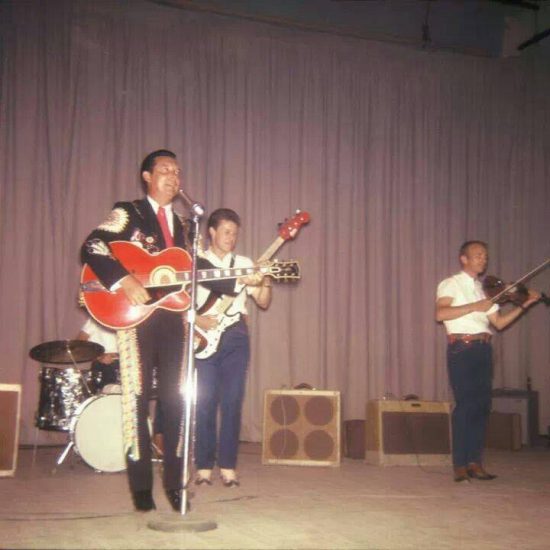

Word quickly spread of Darrell’s harmony ability, and he found his services in demand. “I went to work for Faron, and I worked for Faron for quite a few years,” he says. “After I left Faron, I went to work with Ray Price, and I worked with Ray, fronting and singing harmony with him for a few years. Then I quit and went back to Faron. I worked for Faron for a couple of years and went to Carl Smith, and I worked with Carl Smith and Goldie. Then I went to Hank Jr.” McCall was a frequent vocal presence by the side of Faron Young whenever the Young Sheriff hosted the syndicated TV program Country Style U.S.A.

“One of the best showmen we had in our business,” says Darrell. “He was truly an entertainer, and he had a great voice. I loved his singing. He was ornery. He was a scrapper, but he was a showman and he taught me a lot of stuff. I really admired him. He was like a big brother and a daddy to me. He was great. We got along great.”

There weren’t that many places to play in Nashville itself. “The Grand Ole Opry was about the top end of it, but I stayed on the road quite a bit with Faron and Ray and Carl,” says McCall. “I stayed out on the road the biggest part of the time. But when I wasn’t on the road, I hung with a couple of friends of mine. I practically grew up with them in the music business, Buddy Emmons and Jimmy Day and Big Ben Keith and Roger Miller. We all hung together, and everybody that had a band in Nashville, like Ray and Faron and all of ‘em, they wanted us to work with ‘em on the road. We worked as much as we could, but when we were in off the road, we’d get together and we’d pick and we’d jam and do our own little thing. It was really neat.”

THE LITTLE DIPPERS

1960 was also notable for McCall because he joined a vocal group called the Little Dippers—right after the original iteration of the smooth quartet recorded “Forever,” their big pop hit for the University label. “Buddy Killen, he started a publishing company called Tree Publishing,” he explains. “He had myself and Bill Anderson and Roger Miller and Donny Young as writers. He wrote this song called ‘Forever,’ and he took it over to the Anita Kerr Singers, and they did a little single record with it. They didn’t think it would do much. They released it, and Dick Clark called Buddy Killen. He said, ‘Hey, the song is going crazy! My people want to see the Little Dippers!’

“Well, there was no such group as the Little Dippers right then. So Buddy had to put one together. I just happened to be painting Buddy’s office that day, and he was reviewing a few singers to see if they could sing this one part in the record. And I’m painting up on the walls, and he’s bringing these boys in to sing. They just couldn’t get that one part. Finally Buddy got disgusted. He said, ‘I don’t know what I’m gonna do!’ I said, ‘Buddy, I can sing that part!’ He said, ‘Can you sing this part?’ I said, ‘Yeah!’ So he played it. He said, ‘Oh, my God! Go down and get fitted for a suit right now!’ So one of the first major things I ever did was American Bandstand with Dick Clark as the Little Dippers. Then we went on a Dick Clark tour up the West Coast with Brook Benton and Skip and Flip and the Midnighters and people like that. So it was really a breaking-in experience for me.

“We had a ball. It was one-nighters up the West Coast, and we all got together and we had a big time and partied. Just had a big time.” Darrell did get to participate in the recording of the Little Dippers’ University encore a few months later, which coupled “Be Sincere” and “Tonight” (his fellow Dippers were Delores Dinning, Emily Gilmore, and Hershel Wigginton). “It got quite a bit of play too,” he says.

SOLO RECORDING CAREER COMMENCES

In late 1960, Darrell made his first solo recordings for producer Tommy Hill at Starday Records, although his soundalike renditions of Buck Owens’ Harlan Howard-penned hit “Excuse Me (I Think I’ve Got A Heartache),” Johnny Horton’s “North To Alaska,” and Bobby Helms’ “Lonely River Rhine” weren’t intended to challenge the originals on the charts. “That was back when they had the advertisement out, ‘If you order this record, we have the top ten hits of the day by Top Ten artists,’” he says. “They didn’t say who the artist was, but you’d go in the studio and you’d try to sing as close to the person that had the record out as you could. I did Bobby Helms’ stuff, and I think I did some George Jones things. You’d try to sing like them so they could get the sound they wanted and release the record.”

A far more promising hookup commenced in January of 1961, when McCall entered Owen Bradley’s Nashville studios under the auspices of producer/pianist Marvin Hughes for Capitol Records. With Hank Garland on guitar, Buddy Harman on drums, and in a touch of irony, the Anita Kerr Singers providing the vocal harmonies, the session represented Darrell’s first real shot at stardom.

“Hubert Long got me the Capitol deal,” says McCall. “Hubert picked me up from Buddy Killen. I think what it was, there were just a few of us young guys in Nashville at the time that weren’t married. We could do different kinds of stuff, so I think that’s why Hubert got me. He was brought to town by Colonel Tom Parker. So him and Colonel Tom kept in touch every day on the phone. They were talking about different artists. I think they both had their sights set on us as beinga young rock and roll country artist at the time. I think that’s what it was.”

McCall’s Capitol debut 45 paired two ballads; Roy Drusky and Vic McAlpin provided “Beyond Imagination,” while Darrell scribed “My Kind Of Lovin’” himself. “I never really did claim to be a writer, but I always did write something,” he says. “I did ‘Beyond Imagination’ on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. That was great! Oh yeah, it was good. I had to fly to Philadelphia by myself. I was just a country boy. I’d never been ten miles from the house. To fly over there and meet Dick Clark, that was really a trip. But I’d already met him with the Little Dippers.” “My Girl,” the session’s only upbeat entry, was closer to poppish rock and roll than country, opening with a vocal group riff borrowed from the Gladiolas’ “Little Darlin’” (it was vaulted at the time).

Everyone returned to Bradley’s that June for a followup session (Ken Nelson was listed as producer this time), Darrell providing half of his Capitol encore single with the smooth ballad “Loneliness.” The opposite side was another matter entirely. Written by rockabilly Benny Joy, “(What’ll I Do) Call the Zoo” was about as close to rock and roll as McCall ever ventured, Garland contributing a dazzling guitar solo.

“That record was pitched to me when I was Hubert at the time, and they just insisted on me cutting it. There had been a couple of things out into that—Dallas Frazier wrote one, ‘Alley Oop.’ There were some kind of crazy things on the market at that time, and here comes this ‘Call The Zoo’ thing. They thought, ‘Hey, we’ll follow all that other stuff up with this one!’ So I went in and recorded that, and we released it. It’s crazy,” says Darrell, adding, “I think I’m going to sing that in New Orleans!”

MEETING ELVIS

On one of his trips out West, Darrell crossed paths with the King of Rock and Roll. “I met him in California. I’d recorded a few things, and I had to fly out to Capitol to do some promo pictures with Ken Nelson at Capitol Records. Johnny Rivers was a friend of mine. I met him when I was working with Audrey,” says McCall. “He knew Elvis. So when I flew put to do my photo session at Capitol Records with Ken, Johnny picked me up at the airport and said, ‘Let’s go up to Elvis’s house and visit him a little while!’ I said, ‘Okay.’ So he had just finished doing the soundtrack to Blue Hawaii. We went up and spent the afternoon and evening with him and had the biggest time, playing ball and stuff. Just a super nice guy. But that’s how I met Elvis.

Elvis was a super guy. He had a lot of talent, but he was just one heck of a good guy.”

DARRELL SINGS THE BLUES

McCall was between record contracts later that year when he made a momentary detour into blues after crossing paths with one of the idiom’s top stars out of Chicago. “I met Jimmy Reed downtown,” he says. “I think he was going to the Uptown Club or something. He had his car or trailer parked there on Broadway. And I got to talking to him, and I was telling him I was writing some songs. I said, ‘If I wrote you some stuff, would you listen to it?’ He said, ‘Yeah!’

“So Charlie McCoy and Jim Isbell and Wayne Moss and a couple of the boys had just come to Nashville from Florida, and they were trying to get a start in Nashville. And I got to meet ‘em and hear ‘em pick a little bit, and Charlie impressed the fire out of me. Well, the whole band did. So I asked ‘em if they’d do those two demos with me, and they said yes. So I got in the studio, and I wanted to sound a little different. So I took some little paper match packs and tore ‘em up and stuck ‘em in my jaws to give me a different sound. And we went and cut those two songs that I’d written. I pitched ‘em to Jimmy, and that’s the last I heard of ‘em.

“I never could find out where they went, or whether Jimmy cut ‘em or not, or whatever happened. And all of a sudden I get some wind back from somebody that said somebody out of Florida had released those two songs, and his name was Willie B.! Well, I got to checking and found a record that said Willie B. on it, and it was me! It was myself singing the demos, but evidently whoever released it didn’t know who did the demos, so they just put a Willie B name on it and released it.”

Issued on the Miami-based Terri label, “Bad Mouthin’” and “This I Gotta See” were very credible blues numbers in a laidback groove that would have fit Reed nicely had he tried them on for size. “I never saw him after that,” says McCall. “But he was always somebody that I listened to. I always loved to listen to him and John Lee Hooker and Lead Belly. And I listened to Ray Charles a lot. I listened to all kinds of music.” The German Bear Family label recently reissued Willie B.’s Terri 45 with a snazzy illustrated sleeve sporting a vintage photo of a young McCall. “That’s really neat,” says Darrell. “I’m just tickled to death that they found it and released it.”

FIRST BIG SOLO HIT: “A STRANGER WAS HERE”

By early 1962, Darrell was with a new label. Although Philips was a subsidiary of Chicago’s Mercury Records, McCall continued to record in Nashville, this time with Shelby Singleton at the helm. “I think it was because I was working with Faron, and him and Shelby got to doing some stuff together business-wise,” says McCall. “That’s how I met Shelby. When you’re a young guy in Nashville—I was only 18 when I got there, and I remained single for a long time–the guys that you worked with, their booking agent would want you to record for a major label or a label so they could advertise you on the bill and make more money. But us boys never got any more money. We didn’t know. We were on the bill, but we didn’t get any more money.

“They’d have a billboard of ‘Faron Young—Capitol Recording Artist,’ along with ‘Darrell McCall—Philips Recording Artist.’ That would be on the posters. We didn’t realize it, but we never had any money. A lot of times, you’d be out on the road for a month at a time, maybe work 10 days for $15 or $20 a night, and you’d come home and your car’s been repossessed and your clothes are sitting out on the street corner somewhere. It was rough. We just had no money. We had to hang in there. We did it because we loved it. And I’m still doing it because I love it.”

Waxed in February of 1962, Darrell’s first Philips single was a country-slanted treatment of Larry Finnegan’s breaking pop hit “Dear One” with the ever-present Harman manning the drums and Jerry Kennedy on guitar. “I covered him on that record,” he says. “We took a little ride on it. It was good. I liked that.” Drusky and McAlpin were back to supply the classy ballad flip side, “I’ve Been Known,” McCall soaring pipes surrounded by the Merry Melody Singers. The same date spawned an unreleased version of the rocking “Up To My Ears In Tears,” which Singleton also produced on R&B star Clyde McPhatter at right around the same time.

McCoy’s plaintive harmonica was prominent on Darrell’s jaunty Philips followup “I Can Take His Baby Away,” built around a chunky guitar chord riff that could have suited the Everly Brothers. The mid-tempo charmer emanated from the combined pens of Whispering Bill Anderson and Jerry Crutchfield; McCall performed it on an episode of the Pet Milk Grand Ole Opry Show, hosted by T. Tommy Cutrer, shortly after it was released. The uplifting “A Man Can Change,” the work of pop songsmiths Lee Pockriss and Fred Tobias, graced the B-side.

That autumn, Darrell cut the memorable ballad that would propel him onto the country hit parade for the first time. “A Stranger Was Here” soared to #17 on Billboard’s charts in early ‘63, Bob Forshee’s clever lyrics incorporating talking clocks, window shades, and lamps. “I heard the song, and I thought, ‘I think that’s a great song!’” says McCall. “So I just went out and cut it. It did real well for me. It got up in the charts. I’m starting to do it again right now on our road shows, so it’s been good to me.” Jan Crutchfield was responsible for the other side, “I’m A Little Bit Lonely.”

THE THEME FOR PAUL NEWMAN’S MOVIE “HUD”

From out of the blue that spring came Darrell’s chance to record a Mack David/Elmer Bernstein-written theme song to a major motion picture. “I was down on the riverbank one day,” he recalls. “I was playing with my old .45 Colt. I got off into that fast-drawing thing real heavy. I was shooting my guns, and I had my old hat on, my jeans and boots. I went back up to the house and the phone was ringing. It was Hubert. He said, ‘You’ve got to come in here right now! These people are needing you to record something. I told ‘em you could do it!’ And I said, ‘Okay!’

“So I just jumped in the car the way I was, my old hat, jeans, and everything on. I walked in the studio, and they said, ‘He’ll work! He’s the one that’s gonna do it!’ I said, ‘Oh my God! What is it?’ And it was Elmer Bernstein and them. They had written this song called ‘Hud.’ I didn’t know anything about it. They said, ‘It’s a movie theme!’ So I went ahead and recorded it. Forgot all about it, went home, and the next thing I know they’re releasing the movie. I saw the movie. It was great. But I think my soundtrack went to the drive-ins, the drive-in theaters. And I think they had another soundtrack that went to the theaters.”

Hud was a huge hit in the movie houses for its handsome star Paul Newman, but its theme song didn’t follow suit (McCall’s reading of Hank Cochran’s “No Place To Hide” sat on the flip). “I don’t think I even made any money for recording it,” says Darrell. “There’s a lot of times you do it that way. You’re taking a chance. Throwing it up against the wall.”

Carl Belew was the songsmith on Darrell’s next Philips offering, “Keeping My Feet On The Ground,” twinned with Harlan Howard’s bouncy “Got My Baby On My Mind,” the latter complete with delightfully distorted guitar very similar to Grady Martin’s on Marty Robbins’ “Don’t Worry.” Jerry Kennedy stepped up to produce Darrell’s last Philips date in July of 1964, McCall’s old buddy Donny Young handing him “Step By Step,” a much more overtly country shuffle than any of his previous Philips releases with steel guitar the dominant lead instrument. Hank Garland, his days as Music Row’s first-call guitarist ended by a horrible auto accident nearly three years earlier, teamed with Danny Dill to pen the touching B-side, “Hello World.”

A BRIEF MOVIE CAREER OF HIS OWN

It would be three-and-a-half years until McCall’s next recording session, but he was by no means idle, appearing in three country music films: 1965’s Nashville Rebel, starring Waylon Jennings, was followed by the all-star musical Road to Nashville the following year. In the ‘67 film What Am I Bid?, starring Leroy “The Auctioneer” Van Dyke, Darrell had a few speaking lines in addition to performing as Faron’s bassist and harmony singer.

“I never wanted to be an actor or movie star. It just never did enter me. But every once in a while, they’ll holler at you, wanting you to do something like that. And I’ll give it a shot. If you can make a dollar with it, I’ll do it. That’s the way I looked at it,” says McCall. “We did What Am I Bid? in California. The others we did there in Nashville.”

HITMAKING TIME ON THE WAYSIDE LABEL

The hits began to roll in for McCall once he signed with producer Little Ritchie Johnson’s Wayside label, starting with the Dick Overby-penned “I’d Love To Live With You Again” and “Wall Of Pictures,” authorship credited to McCall and Johnson, in 1968. “Little Ritchie didn’t have too much of an ear for music, but he had been involved with Faron for years,” says Darrell. “I think they started a publishing company together or something. And I got to know Ritchie, and he knew that I was kind of struggling with trying to record. I wanted to record with a fiddle and steel on my records. I wanted to cut the old country stuff instead of this other stuff. I’d been fighting it for years, but they figured a young guy in Nashville, and not married and everything, you should do what they want you to do and be satisfied.

“But I always loved the old fiddles and steel. I grew up with Buddy Emmons and Jimmy Day and Ben Keith, three of the greatest steel guitar players in the world, and Roger Miller. We were the band. So I wanted to record that way. And Ritchie said, ‘You go in and record the way you want to record—put the steel on there, and fiddle, and cut what you want to cut.’ So I went in there and I recorded mostly everything that I’d written up to that point. There was a few other things that I didn’t write on that album. But that was my first release with steel guitar. Lloyd Green played steel on it. Really good!”

“Hurry Up,” a McCall original, proved a C&W chart item for the singer on Mercury/Smash-distributed Wayside in 1969, and “The Arms Of My Weakness” dented that same hit parade for him the following year. Darrell was recording for the American Heritage Music Corporation, still with Little Ritchie behind the board, when one of his songs topped the country charts—but McCall wasn’t singing it. That honor went instead to Hank Williams, Jr., whose rendition of Darrell’s “Eleven Roses” for MGM Records took off like a rocket.

WRITING “ELEVEN ROSES” FOR HANK WILLIAMS, JR.

“I was working with Hank Jr. at the time,” says Darrell. “I had written it earlier. I had the idea for it, I guess maybe 1962 or ‘3. I’d been on the road for about three years, and I hadn’t had a chance to see my mama, and I got to missing her real bad. And I sent her eleven roses in the mail with a little card saying, ‘You’re the missing rose.’ And that inspired that song I did that I later finished when I was working with Hank.

“Lamar Morris got me to sing it for Hank. Before we could get home, I’d already had to sing it eight or ten times to Hank. I said, ‘I haven’t finished writing it yet. I need one more verse.’ After about three days of being home, the phone rang one night about midnight. It was Hank. He was in the recording studio, and he was almost screaming on the phone: ‘You gotta hear this! You gotta hear this! They say it’s a smash! They say it’s a smash!’ I said, ‘What’d you do?’ He said, ‘I just recorded your song, ‘Eleven Roses’! I said, ‘Hank, I’m not through writing it! I need another verse.’ He said, ‘Believe me, you’re through writing it!’

“It was my first number one as a writer.”

A DUET HIT WITH WILLIE NELSON

McCall scored a hit for Atlantic’s country division in 1974 with the Glenn Sutton-produced “There’s Still A Lot Of Love In San Antone,” then moved over to Columbia and scored in ‘76 with “Pins And Needles (In My Heart),” which he produced and arranged himself in cahoots with steel guitar wizard Buddy Emmons. He was still with Columbia the next year and working in the studio with Emmons when his tribute to Bob Wills turned into a duet project with one of Texas’ favorite sons, Willie Nelson.

“Willie had told me, he said, ‘You know, I know how hard you’ve fought all these years to record with a fiddle and steel. You go in the studio. I’ve started a new division of CBS Records called CBS Lone Star. I’d love for you to sign with me.’ And I said, ‘Okay!’ So I signed with Willie, and I went in to record a couple of songs. I wanted to do ‘Lily Dale’ real bad, because it was one of my favorite Bob Wills tunes.

“I started singing it for the band in the studio so they could get the charts down, and Willie walked in. And he walked over to the mic where I was singing, and started singing along with me. And the engineer said, ‘Boy, that sounds good as a duet! Would you all want to do one like that?’ And I said, ‘Well, yeah! It’s not going to hurt me a bit—Willie’s just coming off of “Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain!”’ So basically, that’s what happened, and the record did real well for us.

“Willie told me, ‘I want you to go down to the Lincoln-Mercury (dealership) here in Nashville and pick you up a new Lincoln Town Car. I just bought one for you!’ Mona and I just had our two kids, and I said, ‘I don’t need a town car. I need a station wagon!’ So I ended up with a new Marquis wagon that Willie bought me. So it’s been fun. We’ve stuck together after all these years, Willie and I and all of us. We still stay in touch. A super, super friend.” McCall scored hits into the mid-‘80s, label-hopping from Columbia to Hillside to RCA to Indigo.

A MUSICAL FAMILY TRADITION

Music has long been a family tradition for the McCalls, his Canadian-born spouse, originally billed as Mona Vary, having been in the business since the late ‘60s. “My wife, I met her when I was working with Hank Jr.,” says Darrell. “She had been a featured girl singer with Buck Owens’ show, and she moved to Nashville and started working for Audrey Williams as her drummer and girl singer in the all-girl band that Audrey developed. So that’s how I met her. We started running together and just decided we’d get together. Jimmy Day introduced us.

“We had our two kids, and I’m really proud to say our girl is a writer. She writes a lot of songs and has a lot of songs recorded. And our son has a band, and he still lives in Nashville. He works for the Nashville series that’s on TV on CMT. He’s a set dresser there, but he has his own band and they play a lot. I fly him down to Texas, and he sings my harmony with me on my records, and Mona, my wife’s harmony. He does her harmony too. So we just got it all stuck in our family.”

Both Darrell and Mona McCall record for the Heart of Texas label (he’s been with the firm for a dozen years), the same company that Texas Honky Tonk Revue co-star Frankie Miller is with. “We moved here in 1970. I moved back in ’75 to Nashville, then I moved back (to Texas) in ’81,” McCall says. “We’ve been back and forth for about 40 years. The biggest part of our time has been spent in Texas. We still live here in Texas. We’re right here in Brady, Texas. We have a wonderful record label here called Heart of Texas Records. Tracy Pitcox is the one in charge of the whole thing. We have a beautiful museum, a recording studio, the whole thing. And we have a little house right here in town. I just love it.”

He may technically be an Ohio native, but Darrell McCall is a Texan through and through. “Texas picked me up,” he says. “I’ve gotten fascinated by the old dance halls. And I love to watch people dance. That’s mainly where I want to be. So that’s what happened. They picked me up, and they started playing my records like crazy. And I started aiming at ‘em with my 4/4 shuffles and waltzes and 2/4s, things like that. That’s the music I love, and that’s the people that has kept me alive all these years.”

–Bill Dahl