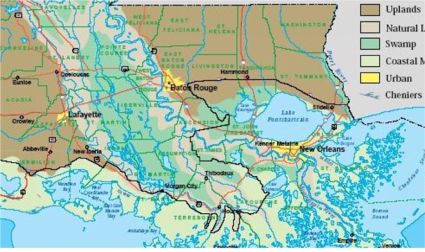

“There have been some unique communities in the Atchafalaya Swamp then and now,” writes Jiro “Jireaux” Hatano in a 2003 article titled “The Music Entertainment in the Atchafalaya Swamp.” “While some of them were abandoned after the great flood of 1927, others are still alive, and a couple of communities are doing well at music entertainment business.” As the great flood of 2011 looms, how many of these fragile but surviving music epicenters will be wiped out?

Many Looziana music lovers are familiar with the on-the-beaten-path Cajun venues such as Angelle’s Whiskey River Landing and Pat’s Atchafalaya Club in Henderson, where Interstate 10 meets the northern end of the Atchafalaya Swamp. Nestled along the Henderson levee, Whiskey River spotlights Cajun and zydeco stars like Steve Riley and Geno Delafose, while Pat’s offers those genres as well as swamp-pop legends such as Warren Storm, Willie Tee, TK Hulin, Tommy McLain, and GG Shinn.

In the relatively large petroleum-powered burg of Morgan City you might find one Vince Anthony, former Looziana rockabilly blazer from the late 1950s who now cranks out countless CDs of well-crafted swamp-pop originals — with the same regularity that sugar cane is harvested each fall — all sung in a voice as smooth as Mello Joy coffee and rich as Steen’s cane syrup. Born Vincent Guzzetta, Anthony and his band the Blue Notes recorded singles for the Hilton and Viking labels, including at Cosimo Matassa’s legendary studio in New Orleans. Later, GG Shinn recorded a scorching version of the Anthony-penned “Devil of a Girl” for Montel Records in Baton Rouge.

Morgan City also served as the post-rock retirement home of former Specialty recording artist and Mac “Dr. John” Rebennack runnin’ pardner Jerry Byrne of “Lights Out” fame (not to mention “Carry On” and the humid south Looziana dirge “Raining.”). Having eschewed the decadent life of dim lights, thick smoke, and loud, loud music in his later years, Byrne died in 2010, an apparently successful nonmusical businessman.

Don Rich is no stranger to the musical venues of Pierre Part and environs, and this writer had the pleasure of visiting one that now is lost to the ages, perhaps a casualty of Hurricane Gustav’s rising waters in 2008: Chilly’s on Lake Verret (827 Shell Beach Road). “The Cajun Country Guide” by Macon Fry and Julie Posner describes the boisterous joint in its latter heyday:

“This is just a great place, a hidden treasure! How could such a wildly popular dance hall exist since the 1930s on a tiny scrap of sinking land 2.5 miles off the Baton Rouge to Morgan City Highway? It helps that the dance hall actually sits on stilts over tranquil Lake Verret and that hundreds of recreational fishermen back their boats in here on weekends. Slow dancers can gaze out the window at moonlight and moss reflecting on the water. The place does not look very old; according to current owner ‘Chilly’ Russo, grandson of the original builder, it was 75 percent obliterated by Hurricane Andrew and few years earlier 50 percent destroyed by Hurricane Juan. After each storm a new plywood floor was placed on the old pilings. A young crowd shows up for the Saturday-night Swamp Pop shows by local singer Don Rich, but the big event is the Sunday-afternoon Cajun dance. Folks drive from Morgan City and Baton Rouge or come by boat from around Lake Verret to dance, drink, and hang out on the patio by the lake.”

Indeed, this place was a true gem, reminiscent of the now-obliterated seafood shacks and camps mounted on pilings at New Orleans’ West End and elsewhere along Lake Pontchartrain. Here’s a video of Foret Tradition playing the Fats Domino classic “Josephine” at Chilly’s (also known as “The Old Lake” club).

Alas, Chilly’s is gone-pecan, but still going strong is the Rainbow Inn on La. 70. According to Fry/Posner:

“The Rainbow is perhaps the quintessential South Louisiana barroom and dance hall. Built in the late thirties, it is a wooden structure with a broad stucco face that sports two round Coke signs and its name is bold red lettering. An old kitchen and dining area in one side is now unused, but the main room with its long bar and wide dance floor still gets action. Bands are scheduled intermittently but usually on Thursday night. The favorite performer is Don Rich, a young local Swamp Pop singer. In its heyday the Rainbow got top Country acts as well as South Louisiana stars like Johnny Allan and Warren Storm.”

Another amazing throwback-style dancehall is Stevie G’s in nearby Belle River, also on La. 70. This joint really packs them in, and during breaks from the live music, the dance floor fills up with young flesh cavorting and gyrating to the sounds of a DJ, generating a sexy, sweaty scene not much different from a late-night Crescent City meat-market bar such as F&M’s or the Goldmine. But when Don Rich or one of the visiting swamp-pop legends takes the stage on weekends, you know you’re in Cajun country, and the elder folk join their younger progeny to cut the rug in grand, effortless, and tireless fashion. Stevie G’s also brings in the torch-bearing young Turks of swamp pop from New Orleans’ West Bank – bands like Foret Tradition, Junior and Sumtin Sneaky, and Brad Sapia – as well as the hugely popular college-and-beer-oriented zydeco stars Jamie Bergeron and Travis Matte from central Acadiana.

Music abounds from the teeming Cajun bayous, but then so does the food – and not just seafood. And some music joints have found new life serving up the grub. One unique venue just outside Morgan City perfects finger-licking-good yardbird in an imposingly squat venue a few miles off U.S. 90: Chester’s Cypress Inn. According to Fry/Posner:

“Nestled in a stand of cypress trees halfway between Houma and Morgan City, this little hideaway has the best fried chicken this side of grandma’s kitchen table. A sign boasts, ‘If the Colonel had our recipe, he’d be a general.’ You won’t find any nouveau Cajun cuisine here, just plates piled high with fried chicken, fish, froglegs, and mounds of crispy onion rings. Chester Boudreaux has passed away, but his children, Calvin Boudreaux and Bobbie LaRose, have kept the Inn much the same as it was when he opened in the forties. The tables are still covered in plastic, and the waitresses still carry cardboard plates laden with golden fried food from the adjacent building that houses the kitchen. Crowds drive the twenty miles from Morgan City and Houma (past dozens of new fast-food franchises) to eat in the homey dining room that once housed a dance hall.”

“Crossing into Thibodaux, we rode near Bayou Lafourche. It was a clammy day, light rain off and on and the clouds were breaking up, heat lightning low on the horizon. The town has got a lot of streets with tree names, Oak Street, Magnolia Street, Willow Street, Sycamore Street. West 1st Street runs alongside the bayou. We walked on a boardwalk that ran out into the water above the eerie wetlands-small islands of grass in the distance and pontoon boats. It was quiet. If you looked you could spot a snake on a tree branch.

“I moved the bike up close near an old water tower. We got off and walked around, walked along adjoining roads dwarfed by ancient cypress trees, some seven hundred years old. It felt far enough away from the city, the dirt roads surrounded by lush sugarcane fields, labyrinths of moss walls in crumbled heaps, marshlands and soft mud all around. On the bike again we cruised along Pecan Street, then over by St. Joseph’s Church, which is modeled after one in Paris or Rome. Inside there’s supposed to be the actual severed arm of an early Christian martyr. Nicholls State University, the poor man’s Harvard, is just up the street. On St. Patrick’s Street we rode past the palatial grand homes and big plantation houses, deep porched and with many windows. There’s an antebellum courthouse that stands next to clapboard halls. Ancient oak trees and decrepit shacks side by side. It felt good to be off by ourselves.

“It was early afternoon and we’d been going for a while. Dust was blowing, my mouth was dry and my nose was clogged. Feeling hungry, we stopped into Chester’s Cypress Inn on Route 20 near Morgan City, a fried chicken, fish and frog legs joint. I was beginning to get weary. The waitress came over to the table and said, ‘How about eating?’ I looked at the menu, then I looked at my wife. The one thing about her that I always loved was that she was never one of those people who thinks that someone else is the answer to their happiness. Me or anybody else. She’s always had her own built-in happiness. I valued her opinion and I trusted her. ‘You order,’ I said. Next thing I know, fried catfish, okra and Mississippi mud pie came to the table. The kitchen was next door in another building. Both the catfish and the pie were on cardboard plates, but I wasn’t nearly as hungry as I thought I was — just ate the onion rings.

“Later on, we rode south towards Houma. On the west side of the road there’s cattle grazing and egrets, herons with slender legs standing in shallow bays – pelicans, houseboats, roadside fishing – oyster boats, small mud boats – steps that lead to small piers running out into the water. We kept rolling on, started crossing different kinds of bridges, some swinging, some lifting. On Stevensonville Road we crossed a canal bridge by a little country store and the road turned to gravel and began to wind treacherously through the swamps. The air smelled foul. Still water – humid air, rank and rotten. Kept riding south until we saw oil rigs and supply boats, then turned around and headed again towards Thibodaux. Thibodaux was neither here nor there and my mind started thinking opposites. Thinking about maybe going up to the Yukon country, someplace where we could really bundle up. By dusk we’d found a place to stay outside of Napoleonville. We pulled in for the night and I shut the bike down. It was a nice ride.

“We stayed at a bed-and-breakfast cottage that was behind a pillared plantation house with sculpted studded garden paths, a cream stucco bungalow that had a certain charm stood like a miniature Greek temple. The room had a four poster comfortable bed and an antique table – the rest, camp style furnishings, and it came with a kitchenette equipped with utensils, but we didn’t eat there. I laid down, listened to the crickets and wildlife out the window in the eerie blackness. I liked the night. Things grow at night. My imagination is available to me at night. All my preconceptions of things go away. Sometimes you could be looking for heaven in the wrong places. Sometimes it could be under your feet. Or in your bed.”

Speaking of Houma, one of the best places to buy swamp-pop and Cajun music CDs (when not listening to the power-packed programming on KLRZ-FM out of Larose or KMRC in Morgan City) is at LA Cajun Stuff in the Southland Mall, a staunch booster of local music from in and around the Atchafalaya Basin, with numerous in-store performances with artists such as Vin Bruce and Treater, always-free bottomless coffee, and the colorful conversation and down-home hospitality of owners Pat and Dale Guidry. A former shrimper from Cut Off — the same town that spawned ex-Saint QB Bobby Hebert and swamp-pop legend Joe Barry — the bilingual Dale is often called out to speak French to the visiting buses of European tourists hungry for a genuine ethnolinguistic experience to write home about. Swamp-pop singer-songwriter and Stomp favorite Jerry Raines of “Our Teenage Love” fame also still calls Houma home these days.

These are just a few of the Looziana cultural islands — and icons — at risk from the spillway’s rising floodwaters. Though this Touro Infirmary baby can’t claim to know even a fraction of them intimately or to have even scratched surface in describing this diverse, multi-ethnic area, I’d feel gut-punched if they are swept away – like so many legendary local venues lost to the eroding sands of time and/or decay (and a tidal wave of parking lots), like the Dew Drop Inn and the Club Tijuana in New Orleans, the Joy Lounge in Gretna, or the Junkyard in Marrero. And America will have lost some of the remaining, endangered vestiges of a rich culture whose roots can be traced back to the Acadians’ Grand Dérangement and whose contributions to the nation — and indeed the world — are incalculable. And like the wetlands that envelop it — irreplaceable.