“I’ve Got A One Way Ticket on This Lonesome Railroad Track”

The Dallas-Fort Worth area was a roiling rockabilly hub during the idiom’s wild and woolly formative years.

Sid King & the Five Strings, Mac Curtis, Gene Summers, Johnny “Hot Rock” Carroll, Ronnie Dawson, “Groovey” Joe Poovey, even a transplanted Gene Vincent were all part of that sizzling late ‘50s scene. Most of them found their way onto the stage of the Big “D” Jamboree, broadcast every Saturday evening from Dallas’ Sportatorium over KRLD-AM, and they regularly rocked rough-hewn nightspots scattered across the two neighboring Texas cities.

Cut from the same bopping cloth as the wildmen listed above, lifelong Fort Worth resident Bobby Crown proudly played the Jamboree too, and he’ll rock this year’s Stomp just as hard as he did the Big “D” more than a half century ago. Born Robert Krajca in the Fort Worth suburb of Crowley on March 7, 1941, Bobby hailed from a musical family; his father, Leslie Krajca, was also a musician. “He played bass in a Western swing band, and they just kind of played for the fun of it, played parties and stuff. Ernest Winnett & the Texas Trailblazers,” says Crown. “There was actually a young guy, he was about 14, that sang for them, Ken “Pee Wee” Short. I kind of got my desire to sing from him.”

Rockabilly was in its primordial phase as Bobby hit his teens. “I saw Elvis when I was about 14 years old at the North Side Coliseum in Fort Worth,” says Bobby. “He wasn’t even the headliner. Hank Snow was the headliner. But Elvis stole the show that night.” Bobby ended up following in his footsteps. “My dad and three other guys had started a country band, and there was four pieces. And the first night they were going to play, the singer didn’t show up. We didn’t have a telephone, so they came and got me ‘cause I’d been singing around the house. I was 14 then. Anyway, they came and got me, and we started playing country. And it was about the time Elvis came along, so I started doing some Elvis stuff and some Conway Twitty stuff, different songs like that. I played a lot of different styles. I played rhythm and blues and country and rock and roll, rockabilly, just a lot of stuff.”

The Krajcas, as they were initially christened for live performances, played The Cowtown Hoedown at the Majestic Theater as well as local bars, serving up mostly country fare. By 1956, Bobby was ready to venture inside a recording facility, so he headed over to Clifford Herring’s studio on West Seventh Street in Fort Worth. A rip-roaring rendition of Big Joe Turner’s “Shake, Rattle And Roll” was the result. “That was actually the first studio recording that I made. It was just a demo record, is all it was,” he says. “I think I was maybe 15 years old when I recorded that.”

Bobby soon assembled his own combo, the Kapers. “My cousin (Eddie Conley) was playing rhythm guitar. He started shortly after we started the band, and he came up with the name of the Kapers. So first it was Bobby Kracja and the Kapers,” he says. “He wasn’t actually blood kin, but he was married to my cousin.” The spelling of the band name evolved. “I think at first he had it C-A-P-E-R-S, and he changed it to K to make it a little different,” says Bobby.

“My dad played the upright bass, and a guy named Jay Cashion played lead guitar. He was older. Well, my dad was older too, but Jay Cashion was older too, and he’d been in the Korean War, and he was a pretty good guitar player. He played on ‘Shake, Rattle And Roll,’” he continues. “We played in some pretty rough places when we first started out. Of course, clubs are kind of rough sometimes anyway, but this was really a rough place we played at. Every time a fight would break out, he was the type of guy that’d jump off of the bandstand and get right in the big middle of it.

“The first place we played at that was actually what you call a club was the Lavida Club. It was right on the outskirts of Fort Worth,” says Bobby. “You’re familiar with Delbert McClinton, right? He was playing right down the street at a place called Jack’s Club on the Mansfield Highway. The Lavida Club was on the Mansfield Highway also. Delbert was playing more or less rhythm and blues and blues music, and we were playing rockabilly and country.” The Kapers gigged at other joints as well, notably the 4010 Club on the south side of Fort Worth, where Bobby wielded his acoustic guitar with a cowhide-covered front.

“I didn’t get out too much to see bands, because I started playing so young. I was always working on the weekends, and going to school. Then I also worked in a service station on the weekends to make a little extra money, so I stayed pretty busy. My dad didn’t have a whole lot of money, so we just kind of rocked along there,” says Bobby. “I did go see Jimmy Reed over in Dallas, and went to see Gene Summers. I like the song ‘Big Blue Diamonds.’ And there were a few country shows around.”

As time went on, the Kapers added additional members. “When we first started out, we didn’t have a drummer. I’m going to say a couple of years down the road, I think it was right before we recorded ‘One Way Ticket’ and ‘Your Conscience,’ we added a drummer and a piano player,” says Bobby. “Gilbert Gray was the drummer, and Butch Evans—his real name was James, but Butch was kind of a nickname–he was a piano player. Played in church, actually, for a long time.”

Local entrepreneur Jimmy Fields invited the band onto his television program. “He had a show on Sunday afternoon on Channel 4 in Dallas called The Country Picnic, and my dad and I guess all of us would watch it every Sunday afternoon,” says Bobby. “I told my dad, ‘We ought to try to get on that, because I think we can do as good as some of those people on there!’ So we were tried out, and we got on the show. Of course, we didn’t make any money on it, but we got on the show and got a little exposure. That’s where I met Jimmy Fields. And there was another guy named Joe Bill. Joe Bill was a partner for Jimmy Fields on all that stuff.”

Bobby must have gone over pretty well on The Country Picnic. Fields also had his own label, Felco Records, with offices at 5513½ E. Grand Avenue in Dallas, and he signed Bobby and the Kapers to cut their debut 45 for Felco in 1959 at Herring Studio, Dale Morgan now on lead guitar. One side was the romping rocker “One Way Ticket,” which Bobby had penned long before he had the chance to put it on tape. “I was around 14 years old, and I’d learned some what I called new chords at the time on guitar,” he says. “I was just trying them out, E and B. Anyway, I was just rocking back and forth between E and B, and I came up with a tune and some words. I wrote it pretty quick, actually.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bcp0hm91ts

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GxSHIZWcvYQ

“When we started doing it, Jimmy Fields, he liked the song ‘Your Conscience’ as the other side of ‘One Way Ticket.’ So he wanted to record ‘Your Conscience,’ and he said, ‘Did you get anything to put on the other side of it?’ And I said, ‘Well, I’ve got a song I wrote quite a while back, but it’s pretty simple.’ So I played it for him, and he said, ‘Well, let’s make a demo of it and see what it sounds like.’ So we made a demo, and it was actually supposed to be I guess what you call the B-side. But the collectors picked up on ‘One Way Ticket.’ They’re the ones that I guess brought it to the forefront.”

The mid-tempo “Your Conscience” actually came from a former musical cohort of the band’s from the Lavida Club days. “I didn’t write it,” says Bobby. “There was a guy named Bob Lumpkin that played in that very first band. And he was an older guy also. He played fiddle and rhythm guitar. And he supposedly wrote ‘Your Conscience.’ He was in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, and he wrote it in the penitentiary.” Fields insisted on a surname change for Bobby prior to the 45’s release. “He liked the song, but he says, ‘Well, your name is gonna be a little difficult,’” says Bobby. “Anyway, he suggested Crown, and I said, ‘Well, fine.’”

Maybe that name change confused Fields, for Felco botched the label typography on Bobby’s single. “They made a mistake,” he says. “When they first pressed it, they had the writers reversed. And they tried to get the writers straightened out. When they did, they put Bob Lumpkin as the vocalist. So there was actually three different pressings.” One listed the artists as Bobby Lumpkin and the Kapers, but eventually things got straightened out.

A raft of additional rockers that Crown waxed for Felco were consigned to the vaults. The hard-driving “Looking For Love,” “Your Lover Man,” and “I Gotta Hurry” (the last penned by Crown and Fields) clearly merited release when they were initially recorded. “My dad and Jimmy Fields kind of had a falling out because we weren’t making any money, you know. And my dad thought we ought to be making some money. After all that, I just kind of played clubs for a long time. And I got paid for the clubs,” he says. “‘I Gotta Hurry,’ it was kind of a demo that I had done over in Dallas while I was still with Jimmy Fields over there. ‘Looking For Love,’ I think I did that in Dallas. Most of that stuff was done on just a little reel-to-reel recorder in a rehearsal room.” The tapes were finally rescued from oblivion decades later by Cees Klop’s Collector label in the Netherlands.

Crown’s encore 45 hit the shelves in 1960 on the Manco label, headquartered in Fort Worth and owned by a gent named Manning. “They had their own studio,” says Bobby. “Howard Crockett, he put out a few singles on Manco.” The Kapers hadn’t changed much from their Felco days. “We had dropped Eddie Conley, the rhythm guitar player. We didn’t have him anymore,” he says. “Mostly it was still the same. We had a backing group called the Beavers that sang background.” Manco almost got their name right on the label as Bobby Crown and the Capers, but confusion continued to reign in the writers’ credits. Even though Bobby wrote “Wait A Minute” and its flip “I’ve Never Had A Broken Heart” the 45 ceded authorship on both to Lumpkin. Each of the tunes spotlighted Crown’s softer side.

“There was a song that came out by Glenn Honeycutt called ‘I’ll Wait Forever,’” Crown explains. “I liked that song, and I kind of got the idea of ‘Wait A Minute’ from ‘I’ll Wait Forever.’ And I wrote ‘Wait A Minute,’ and I felt a little guilty of that. I felt like I stole part of this guy’s song, but I really didn’t.” A latter-day meeting confirmed that Glenn harbored no ill feelings. “I saw Glenn Honeycutt on a show up in Green Bay,” says Crown. “We were up there in Green Bay. And I told him, ‘I got the idea for “Wait A Minute” from your song “I’ll Wait Forever.”’ And he says, ‘Oh, well—“I’ll Wait Forever,” “Wait A Minute.”’”

It was 1966 before Bobby Crown and the Kapers released another single (with the ‘K’ properly restored), this time on the Omar imprint, its offices located at 960 N. Henderson Street in Fort Worth. “We were playing at a place called Omar Khayyam,” says Crown. “That’s where the record label Omar came from.” Surprisingly, Bobby didn’t sing lead on the other side despite the billing; his brother, billed as Johnny Crown, fronted a thundering reprise of Bo Diddley’s classic of a decade earlier, “Diddley Daddy” (Dale Morgan remained the Kapers’ lead guitarist, with Clayton Cox on bass).

“He did a whole lot of singing,” says Bobby of his brother. “He was a pretty good singer, a very good drummer. In fact, some people think that ‘Diddley Daddy’ is me singing, but it’s really not. It’s him. I was singing background on that song.” The other side of their lone Omar release was a soulful remake of Ray Charles’ tortured “Lonely Avenue” fronted by newcomer keyboardist Glen Clark. It was likely the first recording by the Fort Worth native, then a Kaper.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W17dfqWzTPs

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tlhe5wVjp1Y

“Somebody brought Glen out there, because I was needing a keyboard player. Glen was just 17 years old,” says Crown. “Glen was a real skinny little kid at the time, and his hair kind of curled up in the back. And I thought to myself, ‘This is an ugly little son-of-a-gun here!’ But I went ahead and hired him, and the girls loved him, man!” Omar didn’t have long to go. “The guy that owned that club, he was a one-armed guy, and I think shortly after we quit playing there, he killed himself,” recalls Crown. “After that, his wife sold the club.” Clark would soon team with Delbert McClinton to form the duo Delbert & Glen, releasing a couple of early ‘70s country-rock albums before very successfully going their separate ways.

Crown gigged locally for another quarter century or so. “In the early ‘90s, I quit playing in clubs. And I got together with a guy named Mickey Moody,” he says. “I met him through a friend. I used to go over there just about every weekend and write songs and have a few drinks and record some stuff. So I’ve actually got some recordings that probably nobody’s ever heard too much.” However, Bobby’s overseas touring itinerary hasn’t lagged. “There’s a band over there called Wildfire Willie that usually backs me when I go over to Europe, and they are really good. They do ‘One Way Ticket’ just about like the record. It’s amazing,” he says. “I went to Sweden three or four times, and France, Spain, the Netherlands. I went to Finland, England.”

Crown’s overseas following always responds enthusiastically to his presence. “They seem to appreciate it,” he says. “Everybody says it that’s been over there. They say, ‘Well, they know more about me than I know about myself!’” It’s a safe bet that Bobby’s fans at the Ponderosa Stomp will be just as knowledgeable about his musical exploits, and dig him just as heartily.

–Bill Dahl

Great article!

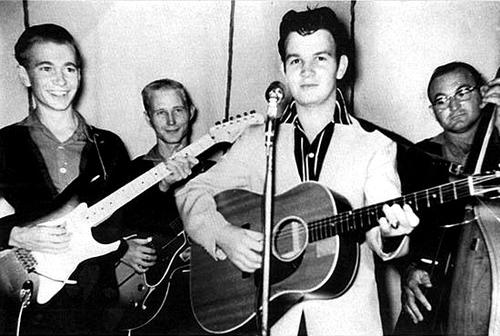

I just read the article and you done a really good job. You have a picture that I don’t have of the rehearsal studio in Dallas.With your permission,I will probably use the picture in my book that I am writing about my life. It is about 80 percent finished.I could use a publisher if anyone knows a good one..

.

1 sentence at the very end of each blog post saying which night and at what time the subject is playing would be most appreciated.

Hi my name is Connie Wilson / Ellington my dad played bass fiddle for Texas trailblazer at cowtown jamboree in Ftworth by grayhound bus station my dad Casorie Odell Ellington and earnest winnett best buds we lived in Everman Texas by earnest most my life

I have actually a signed letter from Bobby Crown. How is he doing today?