WRITTEN BY BILL DAHL

Musical trends come and go all the time on a national level. But in south Louisiana, swamp pop is eternal. That’s been the happy case since the late 1950s, when a phalanx of young Cajun and Creole singers adopted rhythm and blues as their stylistic bedrock. Their combined legacy wouldn’t be labeled as swamp pop for quite some time, but that sound unmistakably emanated then and now from the Louisiana bayou, warm and pungent and enveloping.

Warren Storm is one of the genre’s pioneers, a double threat as a vocalist and rock-solid drummer. He remembers its beginnings vividly. “It originated from the rhythm-and-blues era, from New Orleans,” says Warren. “Fats Domino, that’s where we learned how to play, from listening to him. That’s where I learned how to play. Fats is my idol. He’s everybody’s idol. So rhythm and blues, that’s where it started out. Then they broke down rhythm and blues; it went to rock and roll. But we play the Louisiana rhythm and blues. And you can call it Louisiana rock. Then John Broven came from England and wrote a book about all the artists down here, and he coined the phrase ‘swamp pop.’ So that’s where it originated from.”

“I STARTED PLAYING AT 11 YEARS OLD”

A longtime Ponderosa Stomp favorite, Storm returns on the second night (Oct. 3) of this year’s festivities to offer up some timeless swamp pop. Born Warren Schexnider in Vermilion Parish, he picked up the tricks of the drumming trade from his father. Simon Schexnider played with a country and Cajun outfit, the Rayne-Bo Ramblers. “My dad played drums all his life, and when he’d set up the drums in the house, I learned how to play watching him and going to the gigs,” says Storm. “Then one day he was ill. He couldn’t make the gig. So I went and played. I started playing at 11 years old.”

While attending Abbeville High School, Warren continued his musical apprenticeship with Larry Brasso and the Rhythmaires and saxist Herb Landry’s band, the Serenaders, segueing into R&B with the latter. “I played the guitar also,” notes Storm. “I played the guitar on the weeknights, and on the weekends I’d play drums and sing.” Warren took the vocal plunge in 1956, the same year he formed his own combo.

WEE-WOW: THE GREATEST TWO R&B DRUMMERS IN THE WORLD

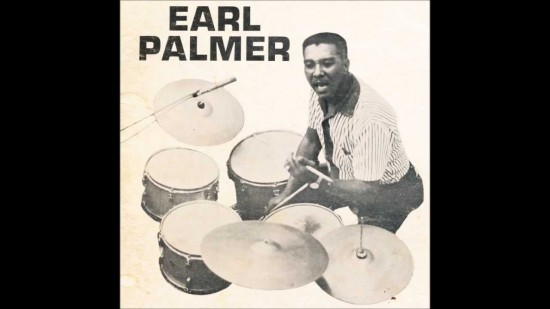

“My first band was the Wee-Wows,” says Warren. “Everybody would say, ‘Wow-wee!’ So I turned it backwards. I said, ‘Wee-wow!’ And everybody would join in and say that.” Storm was developing into one of the region’s most propulsive trapsmen after studying the second line-infused stickwork of two of New Orleans’ finest, Earl Palmer and Charles “Hungry” Williams.

“Those two were the greatest rhythm-and-blues drummers I had ever heard. I was so glad to have met both of them,” he says. “Me and Bobby Charles grew up together. We went to school, and we’d go to New Orleans sometimes. When we didn’t play our gigs, we’d go to New Orleans, and after hours. Lee Allen and Herb Hardesty and Hungry Williams and Paul Gayten, they would play after hours at this Brass Rail (nightclub) in New Orleans. So me and Bobby would go and listen to ‘em. They’d record during the day, and then at night they’d go play a gig. So that was the most wonderful, greatest music I had ever heard.”

A MUSICAL “STORM” IS BORN

Warren traded in his lengthy birth surname for a snappier handle. “In the ‘50s, they had this girl movie-star singer,” he says. “Her name was Gale Storm. So that’s where I got the Storm from, her. My real name is Schexnider, and it wouldn’t fit on a 45 anyway! So Storm was a perfect name.” Ironically, pop chanteuse Gale’s biggest selling platter for Randy Wood’s Dot label was a weak 1955 cover of New Orleans great Smiley Lewis’ “I Hear You Knocking.”

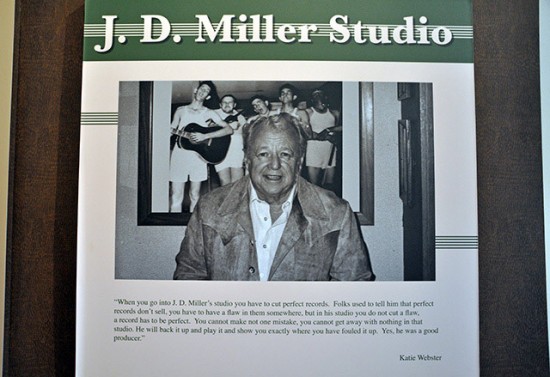

Later renaming his band the Jive Masters, Warren was a regional sensation around Ville Platte and Lafayette. Clifford LeMaire, owner of the Rainbow Inn in Kaplan, La., helped him get together with Crowley, La.-based producer and label owner J.D. Miller, whose expansive stable of artists included blues greats Lightnin’ Slim, Slim Harpo, and Lazy Lester.

“I was working for (Clifford) at the club, and a friend of mine, Willie Guidry, played the guitar in Abbeville,” says Storm. “He told J.D. about me, so this nightclub owner brought me to Crowley for an audition in 1958. So that’s how I got to meet J.D. and audition for him.” Warren demonstrated his versatility at the audition, singing songs by Hank Williams, Elvis Presley, and Fats Domino while accompanying himself on guitar. Miller gave him the thumbs up and got down to business planning Warren’s first session in May of 1958.

“Prisoner’s Song” was an oldie by anyone’s standards, a massive smash way back in the mid-1920s by country singer Vernon Dalhart (Guy Massey, credited as its composer, was Dalhart’s cousin, though the identity of the tune’s actual author is shrouded in mystery). Miller thought it a perfect candidate for a bouncy bayou revival by his latest discovery.

“It was his idea. He rewrote the words,” says Warren. “‘Prisoner’s Song’ was already 30 years old in ‘58. It was already an old hit from the ‘30s and ‘40s. So J.D. sat down and he wrote all brand-new lyrics, and we did that. Then the flip side, he wrote ‘Mama Mama’ so I’d have a 45 record.”

The ebullient “Mama Mama Mama Look What Your Little Boy’s Done” rode an infectious south Louisiana groove, Miller’s house band in Crowley showing itself to be top-notch as usual. “There were some good old musicians from Louisiana, man!” exclaims Storm. “Leroy Castille played the sax, and Guitar Gable played the guitar,” remembers Warren. “Jockey Etienne played the drums on ‘The Prisoner’s Song,’ and I played the drums on ‘Mama, Mama.’”

Instead of issuing the coupling on one of his own imprints, Miller shipped the masters off to Nashville, where Ernie Young operated the Excello label (its leading artists included Jerry McCain, Arthur Gunter, Roscoe Shelton, the Maurice Williams-led Gladiolas, and much of J.D.’s blues stable) and its sister logo Nasco. “The white artists was on the Nasco, and the blues artists was on the Excello,” explains Storm, who found himself with a national hit when “Prisoner’s Song” dented Billboard’s pop charts in late summer of 1958. It also inspired a very similar cover by none other than Fats Domino, though his version for Imperial surprisingly tanked. In other words, Storm had bested his idol his very first time out despite his touring opportunities being fairly limited due to his military service.

“ELVIS WAS DOWN TO EARTH”

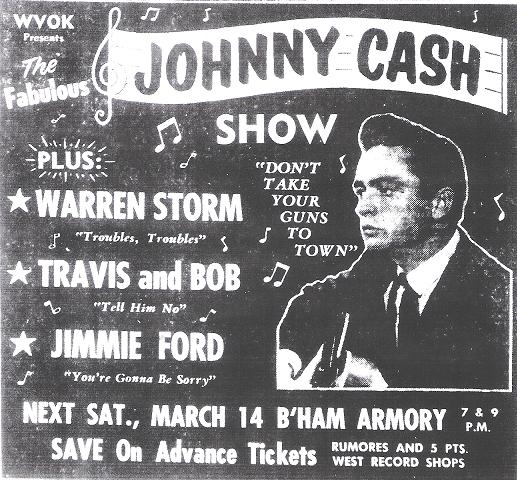

“I couldn’t believe it. If I wouldn’t have been in the National Guard, I could have went — it would have probably went to No. 10 in Billboard, but it was No. 81 in the Top 100. So I made a lot of money playing gigs. Not from the royalties, though!” he laughs. “I toured the South. I did a TV show in Memphis, and I did a show with Johnny Cash in ‘59 in Birmingham. And I went to Texas, Mississippi, Tennessee.

“I met Elvis in 1958, when I did that TV show in Memphis. Wink Martindale was the host, and he gave me a pass to go see Elvis,” he continues. “Elvis was down to earth, just like you and I are talking. That was before he became a megastar.”

Despite its downbeat title, Warren’s early ‘59 Nasco encore “Troubles, Troubles (Troubles On My Mind)” was a joyous Fats-tinged rocker. Like its luxurious mid-tempo flip “In My Moments Of Sorrow,” it was penned by producer Miller. “J.D. was a great engineer, great songwriter. Very easy to work with,” says Storm. “He told me that I was the best artist he ever had. And that really made me feel good. He had a lot of great artists, man.”

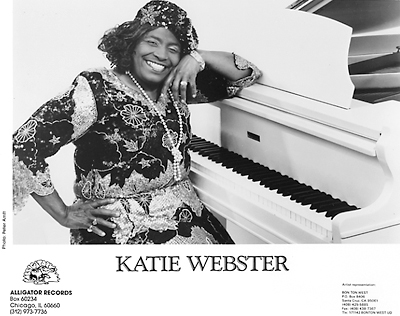

Miller sprang for a female vocal chorus on Storm’s next Nasco offering. “So Long So Long (Good Bye Good Bye)” was a collaboration by J.D. and “Chantilly Lace” hitmaker J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson, though the Bopper had already died in the plane crash that obliterated Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens by the time Nasco pressed up Warren’s single that summer. “That was one of my favorites,” he says. The number rode a rolling Domino-influenced groove anchored by pianist Katie Webster.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hMSPRX34h_U

“Katie Webster was one of my favorites, ‘cause she played on my older recordings, and I played drums on her sessions too,” notes Warren. On tenor sax was another staple of Miller’s sessions, Lionel Prevost from Port Arthur, Texas. “That was my good buddy,” says Storm. Miller wrote its B-side “I’ve Got My Heart In My Hand” on his own.

WAXING WITH NASHVILLE’S HEAVIEST HITTERS

Nasco gave Warren one more shot in early 1960, coupling the delightful rocker “I’m A Little Boy (Looking For A Love)” with another savory remake of a hoary country oldie, “Birmingham Jail,” which harked at least as far back as Tom Darby and Jimmie Tarlton’s 1927 smash. Warren moved over to the pop-oriented Top Rank logo late that year for a one-off produced by Paul Cohen in Nashville with Music Row’s vaunted A-Team in attendance.

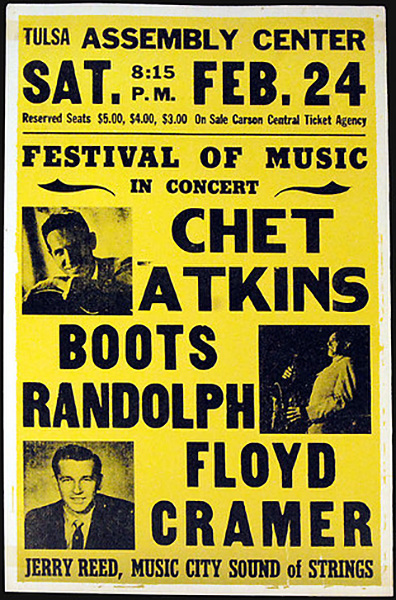

“That was through J.D. He signed the contract,” says Storm. “That was Owen Bradley’s staff band. Boots Randolph and Floyd Cramer and Buddy Harman on drums and Bob Moore on bass. The whole staff band. So I was thrilled to be recording with them.” A fancy string section decorated “Bohawk Georgia Grind,” a dance workout penned by Priscilla Turner (she co-wrote Titus Turner’s “Pony Train” with Mort Garson) and Dave Woody. What did the odd title mean?

“I never figured it out myself!” laughs Storm. “No No,” its tasty plattermate, was more in his wheelhouse, a Miller composition sporting a snazzy sax solo from Boots.

“I HAD TO SING AND PLAY DRUMS AT THE SAME TIME”

Since J.D. operated his own array of labels, he brought Storm onto his Rocko imprint to wax two more Miller compositions, “Oh Oh Baby” and its flip “I Thank You So Much.” “They only had a couple of tracks (in the studio), so I had to sing and play drums at the same time,” notes Warren. The prolific J.D. also supplied both sides of Warren’s next Rocko outing, pairing “I’m Such A Fool” and “Since She Said So Long (She’s Gone).”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rN9ocUsAOJM

“WE’LL NEVER HAVE MUSIC LIKE THAT EVER AGAIN”

Miller moved Storm over to his Zynn label for three more singles, the first coupling “Blues Stop Knocking (At My Door)” (rockabilly Al Ferrier also took a crack at it) and the ever-popular “Kansas City.” “Jailhouse Blues” and a remake of Rod Bernard’s swamp-pop anthem “This Should Go On Forever” formed his Zynn encore. The C&W evergreen “When My Blue Moon Turns To Gold Again” was teamed with “(If You Don’t Want Me) Let Me Know” (penned by Miller under his J. West alias) as his Zynn farewell.

“I like all them songs,” says Warren. “Them old songs, they’re hard to beat, man. We’ll never have music like that ever again.”

But J.D. also kept his eyes peeled for major label hookups for Warren; witness his 1961 Dot single “Gotta Go Back To School,” which Miller scribed (C&W songsmith Vic McAlpin contributed the other side, “I Can’t Love You (Like You Want Me To Do).” For his ‘62 Dot followup, Storm grabbed hold of Hank Williams’ classic “Take These Chains From My Heart,” but he was a little premature: Ray Charles enjoyed a mammoth hit with the tearjerker the next year. Once again, J.D. provided the opposite side, “It’s Hard But It’s Fair.” Instead of recording in Crowley, Storm’s Dot 45s were done at Cosimo Matassa’s New Orleans facilities with some of Fats Domino’s band backing him up. They weren’t the only luminaries on the date.

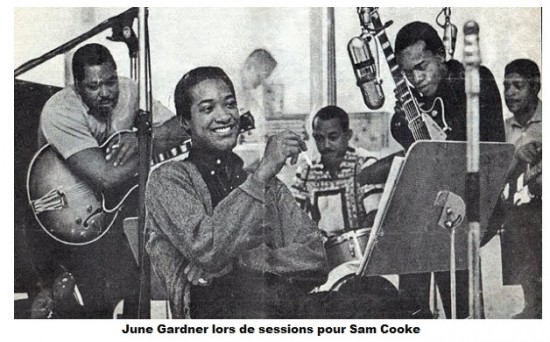

“‘Take These Chains,’ that was Sam Cooke’s drummer playing on that, Sam Cooke’s on-the-road drummer,” says Warren (perhaps it was New Orleans native June Gardner). “I couldn’t play because I wasn’t in the union then, so they were looking for a union drummer, and he just happened to be in New Orleans and they got him to play on the session.”

“SOMETIMES I’D SPEND A WEEK THERE IN CROWLEY”

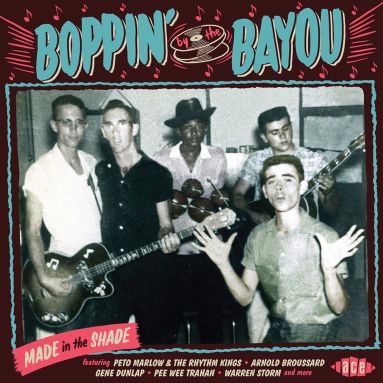

Proving music had no racial boundaries in Acadiana, Warren played a ton of blues sessions for Miller in Crowley, contributing his rock-solid backbeat to J.D.’s house band. “Lazy Lester, Lightnin’ Slim, Slim Harpo, Lonesome Sundown,” he remembers. “All great artists were there that came. Sometimes I’d spend a week there in Crowley, and we’d record just about every day.” That combo was versatile; Ace’s recent CD reissue “Boppin’ By the Bayou — Made in the Shade” closes with a storming instrumental, “Crowley Stomp,” that borders on torrid jazz, Warren cutting loose with a thundering drum solo.

“I really enjoyed that. We did like a little jazz thing there,” he says. “I had forgot about it, and then Ace Records sent me a copy. Man, I keep playing that. I couldn’t hardly believe that we were playing far ahead of our time there! That’s Katie, Bobby McBride on bass, Al Foreman on guitar, and Lionel on sax. I was on drums. Those five musicians there became the staff band at J.D. Miller’s studio in the later years. A great sound for back then, and it still sounds good!”

SWAMP-POP TRIUMVIRATE BATTLES BRITISH INVASION

Storm was a founding member of the Shondells, likely swamp pop’s first supergroup, with Rod Bernard and Skip Stewart. “I was working in a print shop in Lafayette. And they kind of said, ‘What you think about our idea of getting a band together: Rod Bernard, Warren Storm, and Skip Stewart?’ And you know, the work was kind of slow. I said, ‘Well, that’s a good idea. Let’s start it!’ And then in 1963, we did start that band. It lasted for about seven years.

“When the Beatles came out, we got some wigs, and we’d do like a half-hour Beatles show. If you couldn’t beat ‘em, you had to join ‘em!’ You know? We got a lot of work out that. We were working every night!” The Shondells cut a rare LP, “At the Saturday Hop,” for Carol Rachou’s La Louisianne logo early in their existence. “I have one copy,” says Storm. “I kept a copy. I never opened it.”

ENTER THE CRAZY CAJUN HUSTLER

After six years under Miller’s supervision, Storm placed his solo studio career in 1964 in the capable hands of another of the region’s top producers (and certainly one of the most flamboyant). Huey P. Meaux was regaled far and wide in those wild and woolly days as “The Crazy Cajun” and had already introduced the world to fellow swamp-pop greats Jivin’ Gene and Joe Barry. “We worked a lot in east Texas, and I met him over there,” says Warren. “He had a deejay show on Saturdays. And he started booking us. He was a booking agent too. And that’s how I got to meet him like that. I’d been knowing him since ‘58 also.”

Huey focused on recasting the Ink Spots’ 1946 R&B chart-topper “The Gypsy” as Storm’s first Meaux-produced single, the occasion returning Warren to Cosimo’s studio in the Crescent City (Mac Rebennack manned the piano, while Joey Long played guitar). “I was sure glad to do that song. I’m still doing it,” Storm says. With “I Walk Alone” its B-side, the 45 was issued on the fledgling Sincere label, said to be one of Meaux’s many imprints yet confusingly bearing a business address in Delaware County, Pa. (subsequent Sincere releases would cite Huey’s Pasadena, Texas address as the firm’s headquarters).

Ill-fated R&B belter Chuck Willis wrote more than his share of gems prior to his 1958 death. He first waxed “Love Me Cherry” for Atlantic in ‘57; it proved a fine choice for a makeover at that same New Orleans date and ultimately served as Warren’s Sincere encore. “Chuck Willis was one of my favorite artists too,” says Warren, who encountered Chuck’s “Love Me Cherry” co-writer, guitarist Roy Gaines, during a British performance five or six years ago.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oEMwFIzF45I

“JOE BARRY WROTE THAT FOR ME”

“What a talented guitar player and singer,” he says. “He worked with Chuck Willis on the road forever. I was sure happy to have met him.” The lighthearted Fats-styled flip “Jack And Jill,” spiced by longtime Meaux associate Leo O’Neil’s trombone, came from a swamp-pop stalwart. “Joe Barry wrote that for me at Cosimo’s while I was on a session,” says Warren. The churning “Four Dried Beans,” Storm’s next Sincere outing, saw him deemphasizing the Domino vocal influence in favor of a tougher R&B attack; its lilting mid-tempo flip “Don’t Fall In Love” floated on an ethereal choir-cushioned cloud (Huey was credited as composer of both). A sizzling revival of Larry Williams’ stormer “Slow Down” was attached to the atmospheric ballad “Love Rules The Heart” for Warren’s first Sincere offering of 1965.

The spicy, organ-powered Tex-Mex groove pushing Storm’s Sincere platter “Your Kind Of Love” was highly reminiscent of another Meaux production, the Sir Douglas Quintet’s “She’s About A Mover,” which tore up the pop charts the same year. “Too bad it didn’t hit like that!” laughs Warren. “I had been knowing Doug Sahm for a long time. He was a good friend of mine. And they had a track, so I just put my voice on it.” A more melodic organ line ran through the less frenetic B-side, “Memory Tree.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oqCLRFVAgIU

“SHINDIG!” WOULDN’T LET HIM IN

Meaux wasn’t averse to experimentation with Warren, inventing the Kingfish label in 1965 to issue Storm’s grinding rocker “They Won’t Let Me In,” its twangy lead-guitar work bordering on garage rock (a mention of ABC-TV’s “Shindig!” didn’t garner Storm an appearance on the popular rock and roll program). Its plattermate “Sitting Here In the Ceiling (Ain’t It Weird)” lived up to its title with bizarre sound effects and weirder lyrics.

Then Huey reimagined Storm as a blue-eyed soul singer for his ‘66 single on Huey’s Pic 1 imprint, “The Bad Times Make The Good,” its mid-tempo floating feel not that far from what was going on up in Chicago. “Huey had a track,” Warren says. “I put my voice on that track that came from somewhere in Nashville or somewhere. And I just put my voice on that track, ‘The Bad Times Make The Good Times,’ and that was it. That was a little different thing for me.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L84rIK5bJdM

It wouldn’t be Storm’s lone foray into soul-slanted material. A revamp of Bud Deckelman’s country charmer “Daydreamin’,” eventually issued on J.D.’s son Mark Miller’s Master-Trak logo, was nothing short of spectacular. “I did that in Lafayette,” says Storm. “Played drums and sang at the same time. Good horn section there.”

“TENNESSEE WALTZ” BAYOU STYLE

Warren’s last Sincere effort in 1967 coupled an insistent revival of Webb Pierce’s “Honky Tonk Song” with crunchy lead guitar reminiscent of Link Wray and Roy Buchanan and a smooth remake of “Prisoner’s Song.” There was also a splendid horn-leavened treatment that year of “Tennessee Waltz” modeled on Otis Redding’s pleading soul version, pressed up on yet another Meaux-affiliated label, Tear Drop. “‘Tennessee Waltz’ is great,” says Warren. “They played it on WLAC in Nashville, nationwide. It almost became a hit on Billboard. They were playing it quite a bit.” The flip, “Don’t Let It End This Way,” brought the singer right back to the bayou.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t8uUz8eRadQ

Always hustling, Meaux landed Storm a one-off deal with Atco in 1968. Cut at Grits ‘n’ Gravy Studio outside of Jackson, Miss., “Rock Down In My Shoe” came from the combined pens of Cliff and Ed Thomas and Bob McRee, the trio that operated the studio (“Nobody Would Know” was its B-side). Meaux had better commercial luck with his Grits ‘n’ Gravy studio productions on Peggy Scott and Jo Jo Benson and Barbara Lynn.

When Meaux encountered some legal difficulties in 1969, Warren found himself without a label, a situation that lasted until he reunited with J.D. on his Showtime logo in 1974. His first two singles for the new company, “Lord, I Need Somebody Bad Tonight” (penned by Ben Peters) and Merle Haggard’s “My House Of Memories,” found him backed by Bad Weather, who would be his band for the rest of the decade. Both sold well in Warren’s south Louisiana stronghold.

“SEVEN LETTERS” SHOULD GO ON FOREVER

Rebounding from his misfortunes, Meaux struck mega-gold in 1975 producing Freddy Fender’s country blockbusters “Before The Next Teardrop Falls” and “Wasted Days And Wasted Nights.” Huey thought Storm, who played drums on Freddy’s “Swamp Gold” LP, could be steered in the same stylistic direction when he pacted Warren to his new Starflite imprint in 1978. Even there, Warren’s swamp-pop roots shone through on revivals of Jimmy Donley’s “Please Mr. Sandman” and Clarence “Frogman” Henry’s “But I Do” that found him fronting his latest band, Cypress. At Meaux’s Crazy Cajun Records during the early to mid-‘80s, Warren revisited Domino’s “Blue Monday” and “My Heart Is Bleeding” as well as Big Sambo’s “The Rains Came.” There was also a Nashville-cut album, “Heart and Soul,” that came out during the mid-‘80s on South Star, a label not affiliated with either Miller or Meaux. One of its highlights was a revival of Ben E. King’s tortured ballad “Seven Letters.”

’ROUND THE WORLD WITH LIL’ BAND O’ GOLD

The indefatigable Storm has worked with many a swamp-pop aggregation since then, including a long and very successful stint with guitarist C.C. Adcock’s Lil’ Band o’ Gold. “When I was with Band o’ Gold, we toured Australia three times. I’ve got three CDs I recorded with them,” he says. “I played England three times, and Holland about five times, and toured all over the United States.” On his own, he ventured up to Chicago to wax his 2005 CD “Dust My Blues,” an all-blues departure, for producer George Paulus’ St. George label.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S7mGWVYL8tw

Warren is currently in the midst of a bountiful musical partnership with saxist Willie “Tee” Trahan and Cypress, with several CDs to their credit. His days of sitting behind a drum set all night long while belting out his energetic vocals are behind him. Yet he hasn’t given up his kit entirely. “Once in a while I do that. On my regular gigs, sometimes I do two or three songs, sing and play drums. People still want to see me do that,” says Storm, whose pipes remain dauntingly strong.

STILL PACKING ‘EM IN AT THE FAIS DO-DO

“I’ve been doing it for 68 years,” marvels the 78-year-old Storm. “I try to play every week. I do about five or six, sometimes 10 a month. This month I have six of ‘em.” Swamp pop’s appeal around his home base endures uninterrupted. “You know why?” asks Storm. “Because they love to dance. Swamp pop, you can dance. It’s a good dance music.”

Better get your dancing shoes shined up and ready!