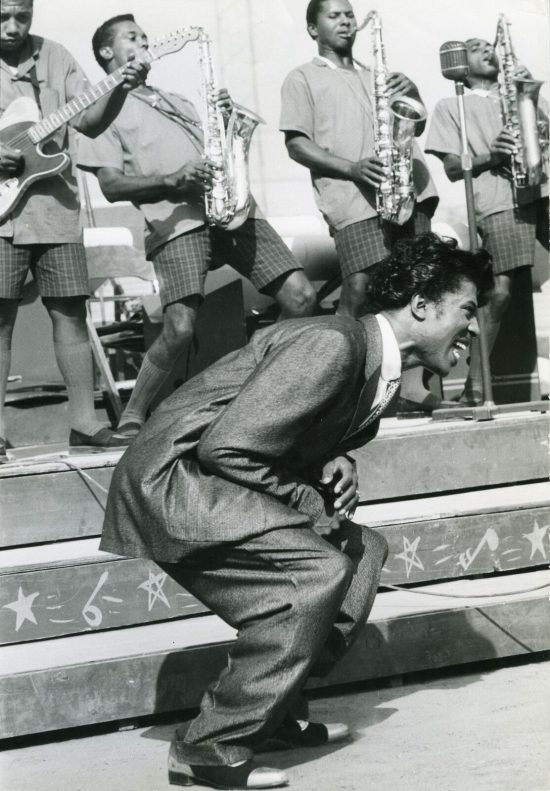

Charles Connor stoked a mighty second-line-infused beat for the Upsetters, very possibly the greatest touring rock and roll band on the planet during the mid-1950s. Of course, the prospect of maintaining a torrid beat behind the volcanic Little Richard would be enough to drive any drummer into third gear and then some. Charles was more than up to the challenge.

BEGINNINGS

Still going strong behind his kit at the age of 82, the New Orleans native will demonstrate his mastery of Crescent City rhythmic intricacies at this year’s Stomp. Connor is best known for his legendary days on the road with Richard, but his resume dates all the way back to 1950 and encompasses a veritable Who’s Who of the era’s R&B luminaries.

“Little Richard, Sam Cooke, Larry Williams, James Brown, the original Coasters, the Ink Spots (not the original Ink Spots, but two or three of the Ink Spots), Shirley & Lee, Jack Dupree, Christine Kittrell, Ernie K-Doe, Clarence ‘Frogman’ Henry, a lot of New Orleans musicians and entertainers. Chris Kenner, Joe Jones, they’re all from New Orleans. I had a chance to play behind all those guys,” says Connor proudly. And it all started for him in the French Quarter.

“That’s where I was born, on Dauphine Street. The house is still there: 610 Dauphine Street,” says Charles. “I used to tap dance for the white tourists. They used to come to the French Quarter and visit the French Quarter, people from all around the world, Europe and all over. I used to tap dance. I was five years old. And my father found out that I had rhythm, and he bought me a set of drums when I was about five-and-a-half years old, a real small set of drums. And I’ve been playing drums ever since.”

Connor’s road to success wasn’t without the occasional pothole. “When I was in the third grade, I used to hit on the desk. I liked the way the desk sounded, the old-time desks at school, like bongos or drums,” he says. “And my teacher said, ‘Charles, you’re nothing but a class clown. You’ll never be a drummer.’ I said, ‘Why?’ She said, ‘Because you’re left-handed. Ain’t no such thing as a left-handed drummer.’” That old axiom didn’t apply in the Crescent City. “The guy that played with Fats Domino, the drummer, they used to call him Tenoo, Cornelius Coleman, he was left-handed too,” notes Charles. “We were the only left-handed drummers out there, and we both were from New Orleans.”

By the time he was 12, Connor was playing local parties. In 1950 he went professional behind a future New Orleans piano legend. “My first professional job was Roy Byrd, Professor Longhair. Mardi Gras Day, 1950,” he says. “I was pretty young.” Opportunities came Connor’s way regularly after that. He backed lovey-dovey New Orleans duo Shirley & Lee, vocalist George “Blazer Boy” Stevenson, and huge-voiced blues shouter Smiley Lewis. “We used to take these little tours,” says Connor, “like 10- or 12-day tours, working out of New Orleans.

“Smiley was a little big-eyed guy, and he had short hair real close to his head. He had big eyes, and he had a big pot gut. He was a nice guy,” says Charles. “He had a little van, something like a little truck. I guess you’d call it a van. On the side of it, it said, ‘Smiley Lewis.’ A nice little blue van. We would be going to Mississippi, Alabama, places like that, and he didn’t want you to fall asleep up in his car because people down South, like the police, might stop you. That’s the way it was tough on black musicians in those days. He didn’t want you to sleep in his car, he said, because the people, they might think we were on drugs or something like that.

“Smiley had a girlfriend up in Nashville, Tennessee. She was kind of short and kind of fat, a little bit. We would play Nashville every three or four months,” says Connor. “He had bought his girlfriend some false teeth, a partial plate. When we went to town about two months later, after he had bought her false teeth, he caught her with another man and he took the teeth away from his girlfriend!

“I played with Joe Jones,” he continues. “Joe was from my hometown. I played with Joe Jones’ big band at the Dew Drop. We played four or five dates around Louisiana. I think I was about 16 years old when I was the drummer. Big band stuff. They were playing blues and swing stuff. He had about 12 pieces. That’s the first time I ever played with a 12- or 14-piece band.”

Another of Connor’s early bandleaders was a fellow Big Easy native, piano pounder Champion Jack Dupree. “Jack Dupree was a hell of a blues piano player,” says Charles, who made his studio debut behind Dupree on November 30, 1953 at a session for King Records in Cincinnati with a New Orleans-dominated band that included saxist Nat Periiliat (one of Connor’s earliest musical collaborators; the two had played together often on jam night at the Club Tijuana), trumpeter Milton “Half A Head” Batiste, and harpist Papa Lightfoot.

“You know another guy I played with before I played with Richard? Guitar Slim,” he says. “Guitar Slim was the first guy I ever seen that went out there in the audience. In those days, he had a long guitar cord. He’d go out there in the audience and play his guitar behind his back, lay down and all that kind of stuff. Those guys were really great entertainers. Nice suits and everything like that, Guitar Slim. Hell of a guy.”

LITTLE RICHARD

His career sputtering after his first singles for RCA Victor and Peacock tanked, Richard Penniman entered young Charles’ world in 1953, and his life would never be the same. “A guy by the name of Wilbert Smith—his professional name was Lee Diamond—we looked alike and everything. I was a little taller than him. We were struggling musicians around Nashville,” says Charles. “I was starving, man. I was kicked out of the hotel room, and I was behind in my rent. Little Richard heard us and brought us back to Macon, Georgia because he wanted New Orleans musicians. Richard had to get my drums out of the pawn shop. He paid for all of that, and he brought us to Macon, Georgia, and that’s when we formed Little Richard and the Upsetters.

“I was 18 years old, and I begged my mother, I said, ‘Mother, I’m doing bad in Nashville, Tennessee. But I want to go with this guy.’ She said, ‘Who is that? Who is that Little Richard? Is that that boy with all that hair on his head, looks like a woman?’ And I said to my mother, ‘Yeah, Mama, but he’s going be famous one of these days!’ I didn’t know whether Richard was going to be famous or not.

“When I first started playing with Richard,” continues Connor, “Richard didn’t have a band. He had a guitarist from Memphis, Tennessee named Thomas Hartwell. He was Richard’s music director, because he was playing with house bands. He was the only one that was traveling with Richard at that time. He was the one that came and told us that Richard wanted to see us and talk to us.”

In Macon, Richard schooled Charles on precisely what kind of rhythmic thrust he envisioned driving the Upsetters. “After we were there for three days, he said, ‘Charles, I want you to go to the train station with me, and I want you to hear the train as it pulls off.’ So he brought me to the train station. He said, ‘We’re going to follow this train about a mile or a mile-and-a-half.’ And we watched this train pull off from the train station. And the train was pulling off. So the train went, ‘ch-ch-ch-ch, ch-ch-ch-ch, ch-ch-ch-ch, ch-ch-ch-ch.’ And as the train picked up, it went (faster), ‘ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch.’ He said, ‘Charles, that’s the kind of beat. I don’t know the values of the notes, but that’s the kind of beat I want you to play behind me when we play.’ I said, ‘Well, you want eighth notes.’ Those eighth notes had a lot of energy.”

The Upsetters, including Richard on piano, backed Nashville chanteuse Christine Kittrell on a 1954 session for the Republic label. Hartwell would depart the ranks soon thereafter, replaced by Texan Nathaniel Douglas. The expanded Upsetters encompassed saxists Diamond (later the co-writer of Aaron Neville’s ‘66 smash “Tell It Like It Is”); Clifford “Gene” Burks; Richmond, Virginia-based Sammy Parker, and hard-wailing tenor man Grady Gaines, whose guitarist brother Roy graces this year’s Stomp. “Grady Gaines came into the band when we went back to Macon, Georgia, and we played around Macon, Georgia for about six months,” says Charles. “Grady had played some jobs with Richard in Texas, because he’s from Houston, Texas, him and Clifford Burks. He had played some jobs with Richard in the early days.”

Another Richmond, Virginia recruit, Olsie Robinson, eventually came in on electric bass, filling a musical void. “I used to have to play that 4/4 on my bass drum to make it sound, before we got the bass player, because we were working our butt off,” says Connor. “I had to play that backbeat loud, almost like a rimshot.” Richard named the band personally. “He wanted us to look different, and he wanted us to look like a bunch of gay guys. And Richard was the only one that was bisexual. Richard was a smart guy. He wanted us to look like that in order for us to play the white clubs. If we’d have looked too macho, they wouldn’t accept us.

“We used to have to act like that and wear loud clothes and act like a bunch of gay guys. We weren’t gay. We were all straight. In other words, to play the white clubs, we wouldn’t be a threat to the white girls. So that’s the strategy he used to introduce rock and roll to these honky-tonk clubs down South. But it was a hell of an experience, because we used to get our hair curled, and used to wear pancake makeup and all that stuff. We looked different, because we were the Upsetters. We were supposed to go and upset every town we played in. Every town we were playing. And Richard would tell the saxophone player—he would tell all the musicians except me; I was sitting down behind the drums—‘If another band jumps off the stage, I want you to jump off the top of the roof of the house!’ He wanted you to outdo every other band. Our band was the first band that ever had dance steps, like a chorus line.”

Although Richard recorded the lion’s share of his non-stop string of mid-‘50s smashes for the Specialty label at Cosimo Matassa’s famous studio in the Quarter under Bumps Blackwell’s direction with Lee Allen and Red Tyler constituting the sax section and Earl Palmer on drums, the piano man preferred the blistering attack of his youthful Upsetters when on tour.

“The same guys that recorded a lot of songs behind Richard, they recorded behind Fats Domino, they recorded behind Shirley & Lee, behind Ernie K-Doe, behind Smiley Lewis, and all those guys. They didn’t want the road musicians to do a lot of recording, so they had a clique,” says Charles. “But those guys couldn’t have gone on the road with Richard, because they were too old. I mean, we were young good-looking guys. Earl Palmer and Frank Fields and all those guys, those guys were about 32, 33 years old. But the tunes that we wasn’t on with Richard, we would do the tunes and Richard would say, ‘Go tell the musicians in the studio how we did it,’ and how he wanted it done.”

According to Connor, Richard’s opening nonsensical cry on his breakthrough smash “Tutti Frutti” came as a direct result of his distinctive drumming. “‘A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop’ came from my drum sound. When he sang ‘Tutti Frutti,’ I would do that (on my drums). That’s on my kick drum, on my drums,” says Connor. “He used to admire Mahalia Jackson, the gospel singer, and that’s where he got that ‘whooo!’ He was crazy about her. Before we met, Richard was with a group called the Tempo Toppers. They were recording for Don Robey, out of Houston, Texas. And I did see Richard when he was playing. I was 17, 16 years old. But they played New Orleans. That guy looked like a star, man. Richard always did stand out.”

JAMES BROWN

When Connor wasn’t barnstorming the nation with Richard, he sometimes worked on the side with another R&B heavyweight then in his formative years. “James Brown and Little Richard had the same booking agent,” he explains. “The guy was Clint Brantley. And when Clint sent us out of town, he sent us to Tennessee and Kentucky, and he sent James Brown to Georgia and South Carolina and Florida. But we were already around Macon, Georgia together.

“We were guaranteed four nights a week—that was like Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. So Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, we worked on the road. I would moonlight with James Brown. And we would work the clubs around Macon, Georgia, like the VFW clubs, the Elks clubs, and places like that. And I’m playing behind James Brown. The drummer always sits in the back. We didn’t have no riser in these little small clubs in those days. We only had drum risers in the big theaters. So I’d be playing behind James and I’d do a little second-line thing, a syncopation on my bass drum. But I was doing that to attract the girls’ attention.

“James Brown would say, ‘Hey, that’s funky! That’s funky!’

“I’d say, ‘I’m doing the second-line!’

“‘I like that! I like that!’

“And he discovered that I put the funk to the rhythm. Because a lot of drummers weren’t using the bass drum that much. But a lot of New Orleans drummers used their bass drum a lot. I got that from the second line. So that’s why he said, ‘Charles was the first to put the funk into the rhythm.’

“Lee Diamond started playing with James Brown, but when Richard came out (to L.A.) to do the screen test for the movie, he left 15 dates behind. So Clint Brantley, the booking agent, he didn’t want to lose the deposits on those dates. So guess who played those dates for him? James Brown! And it was Little Richard’s picture on the placards. But James Brown played Little Richard’s dates. People would complain and say, ‘He don’t look like him!’ James is short. ‘He don’t look like Little Richard to me, but he sounds good!’ But he fulfilled all those dates, and then when Richard came back from the West Coast, James wanted me to go on the road with him too. I said, ‘Well, James, I’m going to tell you—I don’t mind, but I can’t disappoint Richard because Richard was the one that helped me when I didn’t have nothing, paying my hotel rent, and he bought me shoes, and he fed me and everything.’ So that would have been a guilt trip, so that’s why I didn’t go with James Brown. He wanted to take me on the road too. But I remained with Richard.

“When we were on a break up in Oakland, California, I played a couple of jobs with Chuck Willis because the drummer had quit. And Roy Gaines, Grady Gaines’ brother, was the music director, playing a couple of gigs behind Chuck Willis. Chuck was the first guy I ever seen that wore a turban. He had that turban on,” says Connor. “A lot of personality, attitude on stage. A great guy, man. Hell of a performer.”

ROCK AND ROLL MOVIES

Although Earl Palmer was actually playing the singular drum beats on Little Richard’s smashes, when the explosive Penniman mimed his records in the films Don’t Knock the Rock, Mister Rock and Roll, and The Girl Can’t Help It, he brought the Upsetters along to the movie set—so that’s Connor you see drumming in all three flicks, with Grady deftly horn-synching Lee Allen’s solos. “It was an honor to be in the movies back in those days. You’re touring around the United States and around the world, and in places like that people said, ‘I seen you in a movie! I seen you in a movie!’ That’s real exciting,” says Charles. “The Girl Can’t Help It was the biggest one, with Jayne Mansfield. It was Technicolor.”

“KEEP A KNOCKIN’”

The Upsetters didn’t get shut out of recording with Richard altogether. While barnstorming the East Coast theater circuit with the flamboyant rocker, Connor and his bandmates played on one of his hottest smashes, “Keep A Knockin’,” on January 16, 1957. “We were playing the Howard Theater in Washington, D.C. They had a string of theaters, like in Washington, the Howard Theater, the Royal Theater up in Baltimore, and then we would play the Apollo Theatre and the Brooklyn Paramount.

“We were playing the Howard Theater in Washington, D.C., and we did about three shows. We would have about a two-hour or a two-and-a-half-hour break between shows. And what happened was, we went to a little studio up in Washington, D.C., not too far from the Howard Theater, because it was a rush job. We only recorded one tune, and that was ‘Keep A Knockin’.’ It was a little small radio station where we did that. We were all cramped up in there with the drums and the amplifiers and stuff.”

Connor had the honor of kicking “Keep A Knockin’” off in piledriving fashion. “‘Keep A Knockin’’ was the first four-bar drum intro on a rock and roll record,” he asserts. “Richard was saying, ‘I want the guitar to play the four-bar intro.’ So the guitar player, he tried it. Then Richard tried it. He said, ‘I don’t like that.’ Then he let the saxophone play the four-bar intro. I said, ‘Wait a minute, Richard. Let me do something. Let me do a four-bar intro because this has never been played on a rock and roll record!’ It had never been played on a rock and roll record. So I came up with a ‘tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat…’ Richard gave me a thousand dollars for that idea, and that was a lot of money in those days.”

Although the history books claim that Richard and the Upsetters also waxed “Ooh! My Soul” that same day, that’s not how Connor remembers it. “It was done out here in Los Angeles,” he claims. “‘Keep A Knockin’’ was the only one—we didn’t have time to do nothing else.” The band sans Penniman did find the time to back newcomer Don Covay that spring in D.C. on his first solo recording, the insane Richard knockoff “Bip Bop Bip,” that was issued on Atlantic under the unlikely sobriquet of Pretty Boy. “He had long hair,” recalls Connor. “Everybody wanted to be a Little Richard.

“Esquerita, he was hanging around New Orleans at the Dew Drop Inn. When we were playing at the Apollo Theatre, I met Esquerita at the Theresa Hotel,” says Charles. “He tried to be like Richard. A lot of musicians, we used to go out and work in our young days and we’d all come back and jam at the Dew Drop. In New Orleans, you could play music ‘til five or six o’clock in the morning. And the musicians would go back there after their gigs, different places, and they’d come back there and we’d jam all night. A great thing, man.”

Richard and the Upsetters played a memorable concert at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, where the minor league version of the Chicago Cubs played baseball. Naturally, they were dressed for success when they stormed the field. “We played in Bermuda shorts!” he laughs. “My legs were so darned skinny that it was embarrassing. We had to walk across the field in Wrigley Field with shorts on. In those days, it was kind of weird. My legs looked like drumsticks in those days. Lee Diamond’s legs were skinny too. Grady and Clifford and Bassie (Olsie Robinson), they had nice legs. They were much bigger, a little heavier.”

Charles met the future love of his life while on tour with Richard, though he sure didn’t realize it at the time. “Richard didn’t bring the whole band when we went to the Philippines,” he says. “I signed an autograph for a little Filipino girl outside by the hotel. She said, ‘Mister, would you mind signing an autograph for me?’ in broken English. I said, ‘Yeah, okay!’ A big, beautiful hotel in Manila. And I wrote on the napkin, ‘Keep rock and roll in your heart. I hope you come to America some day!’ That’s what I wrote on that napkin.

“In 1981, I saw this beautiful girl up in the supermarket. I didn’t know if she was Chinese, Korean, or Japanese. And I said, ‘What is your name?’ She said, ‘My name is Zenaida.’ I said, ‘By the way, my name is Charles Connor. I’m Little Richard’s original drummer!’ And she said, ‘You can’t be Little Richard’s original drummer.’ I said, ‘Why? I know who I am. I’m not lying!’ She said, ‘An old man signed an autograph for me when I was about five or six years old!’” Before long, they were married.

LITTLE RICHARD GETS RELIGION

Despite all those seminal hits for Art Rupe’s Specialty Records, everything came to a grinding halt for Richard following a tumultuous trip down under during the autumn of 1957. “We played the whole country of Australia. Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps, they were over there with us too. And they had a girl named the female Elvis Presley (Alis Lesley),” says Connor. “But on our way to Australia, they had a four-engine plane. It wasn’t a jet. I never rode in a jet plane in the ‘50s nowhere.

“One of the engines caught on fire over the Pacific Ocean. And the captain got on the p.a. system, ‘Don’t worry, everything will be okay because we can fly with three engines.’ But Richard thought the world was going to come to an end, for some reason. Because that’s the same year Russia launched Sputnik, and all these things were happening. Richard said, ‘Oh, the world is coming to an end soon!’ We were going to play the whole country of Australia. We played about 20 dates in Australia–Melbourne, Sydney, all those places. He said, ‘When I came back to the United States, I’m going to give my life to God. I’m going to be a Seventh Day Adventist minister.’ And he did go to the Seventh Day Adventist college in Huntsville, Alabama.”

Richard’s religious conversion left the Upsetters without their requisite star. “When he came out of show business, he was coming out of the rock and roll business. Sam Cooke was coming out of the gospel field, and he came into the pop field. And Sam Cooke took the band over,” says Connor. “The only thing about playing with Sam Cooke, Sam Cooke only knew two numbers at that time (one was ‘You Send Me’). Now I’m playing with brushes on that tune, not with drum sticks. I’m used to playing, “whop-bop-a-loo-bop, a-lop-bam-boom,’ all that stuff, and he said, ‘Keep on playing!’ We must have played that song about three or four times. The tenor saxophone players, we had three saxophones, they took long solos. But Sam didn’t know no other pop tunes but the A-side and the B-side.”

The suave Cooke would soon write himself a great many more hits, but Charles wouldn’t be playing them with him. “When I left the Upsetters was after we played with Sam Cooke at the Fillmore Auditorium. That was the first time we played with Sam Cooke, at the Fillmore Auditorium,” he says. “The reason I left the Upsetters the first time was because the Army grabbed me. I was drafted by the Army, and they said if I didn’t report back to New Orleans, the MPs were going to pick me up because I was about 10 days behind. But they gave me time to get to New Orleans. I didn’t fly. I went on a train back to New Orleans. And I had to leave then.”

AFTER THE ARMY

Connor picked up right where he left off when he left the military. “After I got out of the Army, I went on tour with a guy by the name of Choker Campbell,” says Charles (the sax-blowing Campbell would later lead the road bands for Motown tours). “After I auditioned for Little Willie John, I never auditioned for another job after I played with Richard. I was working with the original Coasters. Then after that tour, I went back to New Orleans and I started playing with Clarence ‘Frogman’ Henry. I played with him for about a year.

“Then the Upsetters called me back, and I went with the Upsetters. But they weren’t making much money, and I was used to making money. They were just working three days a week, and I said, ‘I can make more money working in New Orleans.’ So I went back and started playing with Clarence ‘Frogman’ Henry. Back then in ‘59 and ‘60, I was making about $125 a week. That was good money in those days. So I went back home to New Orleans. The Upsetters were out there until about ‘64, I think. And after things started getting really bad, they cooled it.”

Charles had relocated to Los Angeles long before he met his wife Zenaida there, leading his own West Coast Upsetters during the ‘70s and remaining there to this day. He’s been busy in recent years, recording an EP under his own name (Still Knockin’) with vocalist Kate Flannery and writing his 2015 autobiography, Keep A Knockin’—The Story of a Legendary Drummer. Connor’s trip home to appear at this year’s Stomp represents a special treat for ardent first generation rock and roll aficionados.

“I don’t like to tour,” he says. “I was on that road 22 years, and I got tired of the life.” Yet once upon a time, the allure of that same road was irresistible. “You don’t know that you’re creating something that’s going to last a long time,” says Charles. “We were a bunch of young kids out there, having fun. We thought that was a natural thing. When you’re out there with a superstar, it’s a hell of a feeling. You walk through an airport and people are bowing down, or you’re walking in a hotel and people give you all kinds of stuff. They want to buy you this, buy you that, buy you a drink. That’s a hell of a feeling, man. But then when you come off the road, you’ve got to face reality. But that’s a hell of a feeling to be out there with a hot guy like Little Richard. A powerful feeling. We had a lot of power. We had women in every town we’d go to.

“It was a great experience.”

–Bill Dahl