WRITTEN BY BILL DAHL

“You can pretty well tell my drumming on that Sun stuff from somebody else’s,” said J.M. Van Eaton. “I guess it’s a little bit different.”

A profound understatement.

During his stint as primary house drummer at Sam Phillips’ Sun Records, Van Eaton stoked his fiery beat on the biggest hits of Jerry Lee Lewis, the last Sun recordings of Johnny Cash, and the hottest rockers Billy Lee Riley ever laid on tape. He played on Sun classics by Roy Orbison, Hayden Thompson, Ray Smith, Warren Smith, and Bill Justis. And yes, you can readily discern J.M.’s reflexive, fluid stickwork from that of the other timekeepers at 706 Union.

Van Eaton showcases his singular sense of timekeeping at this year’s Ponderosa Stomp in the fine company of Deke Dickerson and his band. Expect the walls of the Rock ’N’ Bowl to shake with a savage rockabilly rhythmic thrust.

Born in Memphis in December of 1937, J.M. had to await his turn to sit behind a drum kit when he was just starting out. “I went through the Memphis public school system, and when you got into middle school, you had a choice,” said Van Eaton. “You could either take vocal or band, so I put down for band and tried to be a drummer. But they had too many drummers, so they put me in the trumpet section. I tried that for a year, and I wasn’t much of a trumpet player. So they finally let me go and try out drums. I think I was probably in the eighth grade then. And then I fairly rapidly moved up in that, so I got my first little band, played my first talent show when I was in ninth grade, and kind of took off from there.”

Van Eaton dug the top big-band trapsmen that he heard growing up (especially Buddy Rich), and he grooved on the rhythms emanating from a local black church on Sunday evenings. The second-line beat that Earl Palmer pounded out in New Orleans also left an indelible mark. “I thought Earl’s early stuff was a pretty driving force for Little Richard,” he said.

“I love Dixieland. My first little band was a Dixieland band, which was pretty cool,” J.M. said of his Jivin’ Five. “I listened to the Dukes of Dixieland, coming from the Roosevelt Hotel in New Orleans, so that was kind of an early influence on me. I’m not sure who their drummer was, but I bought a couple of their albums and liked their stuff. Because that was kind of before rock and roll hit big.”

The first time Van Eaton strolled through the doors of Phillips’ Memphis Recording Service, he was there to play behind a friend. “I went in with a guy named Jim Williams, who was a local guy who had got an audition with Sam to go down there and pitch a couple of songs,” said Van Eaton. “He had a big dance band. He would play local gigs here in Memphis, and he was using me as a drummer. Then he kind of condensed that down to a little combo. We went in there and put these songs down. That was when Sam was doing the engineering. It didn’t go over too well, but he loved Jim Williams, and he finally put a record out on him.”

J.M. switched his musical emphasis when Elvis took hold of the nation, leaving the Dixieland beat behind to form a rock and roll combo called the Echoes. Their jaunt to Sun proved auspicious for the teenaged drummer. “The trip that got me in the door was that trip with my little high school band. We went in to make an acetate. Jack Clement had just started to work there. He’d just got Billy Riley a deal, and they were looking for a band to back (him) up,” he said. “They kind of liked what they heard from our little band that came in for that acetate, and they hired me and they hired the bass player, Marvin Pepper. So we became part of the Little Green Men right off the bat.”

Riley, a revered Stomp regular until his 2009 passing, was a wildman behind the mic, a handsome rockabilly pioneer who should have been a much larger star than he ultimately became. As a charter member of the Little Green Men, Van Eaton was the perfect drummer for him. Guitarist Roland Janes was already on board; the two would form the backbone of Sun’s house band for years to come. “Roland and I hit it off pretty quick, and we started getting a lot of session calls,” said J.M. “One thing led to another, and next thing you know, man, they’re calling you on just about everything.”

“I THOUGHT WE HAD THE BEST BAND ANYWHERE”

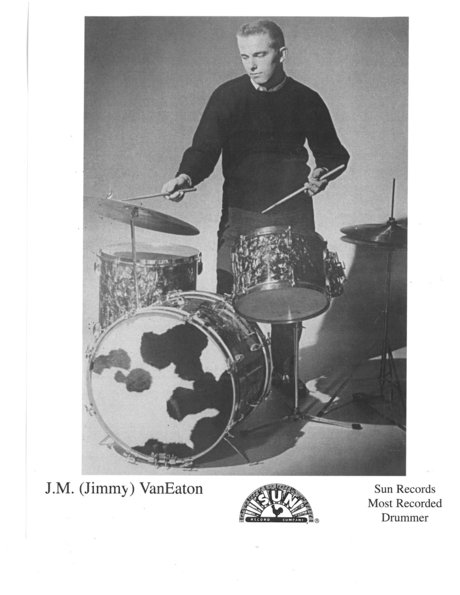

Phillips named Billy’s band. “Sam was good at coming up with these crazy names, like Jerry Lee Lewis’s Pumping Piano,” said J.M. “He thought the band needed some kind of crazy gimmick name, so he called us the Little Green Men.” They were outfitted in bright green stage suits made from heavy material likened to that covering a pool table. Van Eaton sported a calfskin head on his bass drum.

J.M. gigged with Riley even before they dropped by Sun to wax “Flyin’ Saucers Rock & Roll” in December of 1956. His thundering drums congealed with Roland’s lead axe and Jerry Lee’s 88s to drive Billy’s insane rocker to stratospheric energy levels. “It was kind of a hot topic of the day, people seeing all these UFOs. It was pretty cool,” said J.M. “It’s a classic. You don’t even have to hear the lyrics. When you just hear that kickoff, you know what the song is. And very few songs can you say that about.

“I thought we had the best band anywhere,” he continued. “We could do it all. That band, even when Roland left and we had (saxist) Martin Willis and those guys, we played all over. We were a hot band in the South, but we never could get that hit record at the time to break through on the big stage. Our song, ‘Flyin’ Saucers,’ was like No. 1 in Tulsa, Okla., but then nobody’d hear of it in L.A. I mean, we just couldn’t get it quite over the hump. That’s why I guess I kept relying on that band. I thought we were going to have a breakthrough hit one day and we’d be rich and famous. But it sure didn’t work that way.”

BLAZING “RED HOT” SHOULD HAVE BEEN A MONSTER HIT

Riley’s next Sun offering, a souped-up revival of ex-Sun bluesman Billy “The Kid” Emerson’s “Red Hot,” packed a punch at least as lethal. Waxed in January of ’57 with Van Eaton supplying the backbeat and Janes unleashing two killer solos, it should have made Riley a national star.

“‘Red Hot’ was another good record, man. We got a lot of mileage out of it, but it still didn’t break through,” said J.M. “There’s several different arrangements of that song before we came up with the one that they released. But that was the beautiful part about Sun. They gave you an opportunity to experiment with different arrangements until you’d come up with something that really clicked.” However, Phillips was obsessed with promoting Jerry Lee by then, and “Red Hot” slipped through the cracks.

J.M. had been on hand when The Killer first turned up at Sun in November of ’56, hungry to record. “Jack Clement was the engineer, and I had been playing with Billy Riley,” he said. “Jerry Lee came up, just him and J.W. Brown, to audition. And Jack called me and wanted to know if I could come down and play some drums behind this guy who didn’t have a drummer or a bass player, or actually have a band. J.W. played rhythm guitar. And so I did that. And actually, out of that audition came the song ‘Crazy Arms.’ It’s just got the drums and piano on it. It doesn’t even have the rest of the band, not even on the thing. So at the very end of the song, I think Billy Riley, who was hanging out down there that day, came in and picked up a guitar and hits a chord right on the end. It just happens to be the right chord. So that’s pretty weird.

“I HAD NEVER HEARD ANYBODY PLAY LIKE THAT”

“I really didn’t know what to think, to be honest about it, because we had been playing with different guys that looked more the part of rock and rollers. When he comes in, he’s got this goatee, for whatever reason. He didn’t look like any of the rock and rollers that I had been seeing. And J.W. had had an accident at the Light, Gas & Water where he worked, and his arm was in a cast. And I’m thinking, ‘Man, I can’t believe you got me out to come down here to do this,’ you know? But when the guy started playing the piano, then right away you realized for sure that was — I had never heard anybody play like that.”

Van Eaton would play on nearly all of Jerry Lee’s Sun output through 1960, including his immortal ’57 smash “Whole Lot Of Shakin’ Going On.” “We’d gone out on a couple of shows with him, because ‘Crazy Arms’ was already starting to get in the charts, and he was getting some bookings,” said Van Eaton. “In order to pay the bills, we played some clubs. And that required a four-hour gig. And so none of us having played together before, I didn’t know if he had four hours worth of music or not. So we were just playing any and everything that anybody could think of that we all seemed to know.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RFxRTLmtsbE

“We were over at a club called Twin Gables in Blytheville, Ark., which I remember fairly well. The bandstand was so small that the bass player and the guitar player had to stand out on the dance floor. And Jerry and I got back in this little cubbyhole. When we started playing, man, all this dirt started falling out of the top of the ceiling. I guess they hadn’t had anybody in there quite as forceful as we were.

“PLAY THAT ‘SHAKIN” SONG AGAIN”

“So we played that song, and the people hit the dance floor and they loved it. And they kept coming back saying, ‘Play that “Shakin’” song again!’ So we probably played that song four or five times in that particular night. So when we got back in the studio again to try to put down some other tracks, because we knew that we were going to have to have a really good record because ‘Crazy Arms’ was a cover record. I mean, Ray Price, he’d had a big hit on that thing. So Jerry said, ‘Well, why don’t we do that “Shakin’” song?’ Or somebody suggested that we do that song that went over so well. So we did it, and man, the very first take, we got through it, and Jack, I remember him saying, ‘Pick the tempo up a little bit.’ So we tried it again, and got a little faster version, and he said, ‘No, the first one sounds better.’ So that was it!”

Recording with Lewis was always an adventure. “Everything was spontaneous. You couldn’t rehearse. About the most effort we put in to any song we cut was this thing called ‘It’ll Be Me.’ And the reason for that was Jack Clement wrote that song, and he wanted as good a cut as he could get on the thing. So we tried it several different ways,” said J.M. “It was on the back side of ‘Whole Lotta Shakin’.’ So he came out OK even though it wasn’t the A-side. But we spent more time on that particular song than anything else Jerry did.”

JERRY LEE “LIABLE TO GO IN ANY DIRECTION”

Van Eaton’s drums were just about all the musical support Lewis required on his next blockbuster later that year, “Great Balls Of Fire”; the electric bassist is all but inaudible, and there’s no guitar at all. “A lot of times Jerry and I would be in the studio by ourselves, and a lot of those songs are just the two of us,” noted J.M. “Breathless” made it three smashes in a row for Jerry Lee during the spring of ‘58.

“The very ending of that song, where we hit those two little licks there at the end, it seems like we had a little problem with that,” said Van Eaton. “With Jerry, you had to be able to make eye contact so you could know where he was going, ’cause he was liable to go in any direction. And that song, the timing is just a hair different.” “High School Confidential,” a supersonic theme song for a potboiler flick with Mamie Van Doren that opened with Lewis singing the song from the back of a flatbed truck, came next. “I just think that’s one of the unsung rock and roll records of all time. That’s a great record,” said J.M. “And Roland, I just thought it was a great guitar solo. Man, I think it’s one of the best ones he ever had!”

“SOME THINGS ARE JUST DESTINED TO HAPPEN”

When news broke that Lewis was married to his 13-year-old cousin Myra Gail, the scandal stopped “High School Confidential” dead in its tracks on the charts. Sun kept trying to resuscitate his flagging fortunes, but Jerry Lee would be mostly absent from the national hit parade for a while despite some great recordings. “Jerry Lee Lewis and his style of playing and my style of playing were identical,” said J.M. “I think it was a godsend that we showed up there at the same time. Some things are just destined to happen, and that was one of ’em.”

Van Eaton had honed his own distinctive technique, distinguished by his crisp cymbal work. “I put a lot of tape to tone it down so it wasn’t necessarily ringing through like if it was just a normal ride cymbal without anything holding it back,” he said. “So it did have a — I won’t say a closed hi-hat sound, but it was somewhere a ride cymbal and that.” Sun’s unique studio properties also factored into the way Van Eaton played.

“I think the fact that they only had that one microphone, and you kind of mixed your own sound right there,” he cited as another factor in his approach. “They could bring you up or down. We played softer in the studio than they do today. If you couldn’t hear the piano, which was not amplified, and the vocals, which you didn’t have any earphones — if you couldn’t hear those, you were playing too loud. So you played soft, and then the engineer could bring you up inside if he wanted to make you sound like you were playing a lot louder than what you really were in the studio. I think that helped a lot.”

ROY ORBISON “COULDN’T WAIT TO GET MOVED”

There were plenty of potential stars hanging around 706 Union and Taylor’s Café next door, though a disenchanted Roy Orbison split in 1958 after cutting some fine rock and roll for the label. J.M. played on his “Sweet And Easy To Love” and “Devil Doll” in late ’56.

“I liked Roy. I thought he was a super guy. We became pretty close friends, hung out together a good bit before he left Sun. He was pretty upset towards the end because of the material they were giving him to record. ‘Chicken-Hearted,’ stuff like that. He didn’t like that. When you stop to look at the great songs that he’s recorded, then go back and listen to that, you could tell that they had moved him way off center from where he wanted to be. And it hurt him personally,” said Van Eaton. “(Sun arranger Bill) Justis wrote that song or had something to do with it, so they almost forced him to record the thing. And he didn’t like it. He was bitter. It really upset him, and he couldn’t wait to get moved.

“Sam, at that time, was all wrapped up with Jerry Lee. He put a lot of his artists on the back burner, and basically the artists suffered for it, and Sam suffered for it.”

Justis’ writing and arranging skills were important to Sun, and the saxist ended up with the first big seller on Sun’s new Phillips International logo in 1957 with his danceable instrumental “Raunchy.” “I liked Bill too,” said J.M. “He used me on just about everything he did. I played on ‘Raunchy.’ I played on all of his cuts. I think he kind of looked down on rock and roll. But at the same time, he booked these gigs, and he would take his big band, and they would play for the big ballroom type stuff. And then we’d be the floor show. He would bring us out, and the people would go crazy. And then they’d go back to their big-band stuff. He liked it, but he knew where the money was coming from. He got more money booking us than he did booking the big band.”

“I DON’T THINK JOHNNY REALLY WANTED A DRUMMER”

As his time at Sun neared its end in 1958, Johnny Cash began to experiment with using a bigger band under Clement’s supervision complete with vocal group to augment his trusty longtime accompanists, guitarist Luther Perkins and bassist Marshall Grant, who had backed him so nobly on his smashes “Folsom Prison Blues” and “I Walk The Line.” Van Eaton beefed up The Man in Black’s backbeat on “Guess Things Happen That Way,” “Home Of The Blues,” and “The Ways Of A Woman In Love.”

“I don’t think Johnny really wanted a drummer, because he had been quite successful without one. But they were starting to do more things, bigger arrangements,” said J.M. “But it went well, really, once he realized that it was the sound was going to still be good. Then he was OK with it.”

“I WENT WITH CONWAY AND THEM TO CANADA”

Tenor saxman Martin Willis joined the Sun house band along the way, bringing some R&B feel to the proceedings. “Martin and I went to school together,” said Van Eaton. “We both were going to go out to the University of Memphis and play. But we started making money making music, which is what we were going to go to college to learn to do in the first place. So we thought, ‘What the heck,’ you know?

“He was playing with Conway Twitty and actually called me one day and said Conway needed a drummer. So I went with Conway and them to Canada, and Willis and I struck up — he was part of my band, we were in a high school band. He wasn’t with the Echoes, but we played a lot of talent shows together. We were good friends, and are still good friends. Anyway, he came with me back to Riley’s band, so that kind of got him in the door at Sun.”

Phillips and Clement differed when it came to production styles. “Sam was more of a sound guy. He was listening for the different sounds, when it was too loud. Jack was more of a musician who could tell you, ‘This needs to go in this key,’ or ‘You need to move it in a different key,’ or whatever. He would throw out those suggestions along with his ability to play. But Sam, not being a musician, but he was definitely a sound man,” said J.M. “It was just more like ‘go get it’ type arrangements. All of us had been playing in different clubs, and the basic thing that you were trying to achieve was danceable music. If they couldn’t dance to it, then you had to get it in a groove so people could do that. That was a big thing, dancing, at the time.”

“YOU WOULD GET PRETTY CREATIVE IN THAT SUN STUDIO”

Although he joined the Sun family as more of a songwriter and session pianist, Charlie Rich emerged as a promising new artist in 1958. Signed to Phillips International, Rich cut a hit late in ’59 with his self-penned “Lonely Weekends,” driven by J.M’s innovative bass drum work. The song sprang from a quasi-gospel number Rich had waxed earlier in the year, “Big Man,” that he had nothing to do with composing.

“Sam had brought a guy (Dale Fox) in to do ‘Big Man,’ and the guy couldn’t get the vocal,” said Van Eaton. “Sam very seldom if ever let an outsider come in and cut in that studio that wasn’t going to be on his label. And this guy that wrote this song — it was a gospel song — rather than waste a day, he asked Charlie to give it a shot. So that’s when I got that bass drum thing. It actually came first on ‘Big Man,’ when we cut that. Sam told Charlie, he said, ‘Now, man, if you can write a song with that same feel, then I think we’ll have something!’ That’s when he wrote ‘Lonely Weekends.’

“Normally they didn’t let you play the bass drum. There were so few microphones that they would put the bass and the bass drum on the same mic, so actually you just hit it harder. So I was trying to get that little gospel feel myself. It was just one of them natural things. You would get pretty creative in that Sun studio, because if you’re not, you’re going to get left behind. So most all that stuff was pretty spontaneous and creative. That’s what made it so popular, made it what it was. And it just happened to fit.”

“A LITTLE DIFFERENT SOUND” AT 639 MADISON

Things were changing at Sun at the dawn of the new decade. Clement and Justis had exited the previous year. Phillips constructed a spacious new studio nearby at 639 Madison Ave. that was more technically advanced yet often failed to capture the same riveting sound that made 706 Union such a marvel. “They get over to the other studio, where they had that big, humongous echo chamber, and they started throwing all that stuff on there, which gave it a little different sound,” said Van Eaton, who decided it was time to make his exit soon after the new facility opened for business.

“Scotty Moore was the engineer,” he said. “I played on a lot of Charlie Rich’s stuff that was cut over there. The sessions started slowing down. The hits stopped coming. And it became kind of a money thing, really, and I had to do something different.” There were freelance opportunities, Van Eaton playing on Narvel Felts’ Pink label sides. He gravitated to a new local operation, Rita Records, launched by his old cohorts Riley and Janes in partnership with Ira Lynn Vaughn. “They teamed up and opened that thing up,” said J.M. “We would cut those records over at Royal Studio.”

“THEY WANTED TO CUT SOME INSTRUMENTALS ON ME”

Rita nailed a big hit in 1960 with Harold Dorman’s “Mountain Of Love” (which J.M. played on), and for the first time Van Eaton was asked to step into the spotlight as a bandleader. “They wanted to cut some instrumentals on me, but it didn’t do as well as ‘Mountain Of Love,’” he noted. “Foggy” and plattermate “Beat-Nik” hit the shelves credited to Jimmy Van Eaton, while the grooving original “Midnite Blues” and a brisk instrumental rendition of “Bo Diddley” on its opposite side emerged on Rita’s sister label, Nita, credited to J.M. Van Eaton and The Untouchables. The drummer indulged in a solo here and there, underscoring his inventiveness.

Though the studio work eventually dried up, J.M. stayed musically active in the clubs. “Roland and I and a guy named Prentiss McPhail (on bass) and (pianist) Tommy Bennett put a band together, and we played in this club for about five years,” said Van Eaton. “I was singing a lot in this club, because you’ve got these four-hour nights, three nights a week. Man, we were trying to help one another out, so everybody in the band was singing some.”

J.M. cut a version of “Jump Back” as his vocal debut in 1964 at Janes’ Sonic Studios, though it wouldn’t see light of day for decades. “That was one that we were doing. And it was pretty popular, so Roland, we were down at his studio one day messin’ around. So we put that down,” he said. “That’s Travis Wammack on guitar.” Van Eaton also waxed a vocal treatment of “Something Else” with Roland that was similarly dispatched to the vaults until the Bear Family imprint of Germany belatedly issued both sides.

“A LOT OF PEOPLE … DIDN’T GET THEIR JUST DUES”

By 1979, Van Eaton had turned his sights to playing with a gospel group, the Seekers. The drummer wrote prolifically for their album, released on a label owned by local producer and fellow Sun alumnus Stan Kesler. J.M. settled into a day job as an investment banker in 1983, though it didn’t interfere with his musical interests.

“A friend of mine was in this business, and they were telling me about it. I thought I’d give it a shot,” he said. “I could still kind of come and go as I wanted to, so it didn’t hinder me from playing if I wanted to continue music. And it also financed a lot of projects that I wanted to do. It’s hard to make a living in music, make a good living. You can survive, but I have a family. I wanted to do more than just that. I wanted to be able to do as much as I possibly could do, and I couldn’t do that playing music. For some reason I never got the money that you should have gotten from playing. And neither did a lot of other people. It wasn’t just me. It was a lot of people that didn’t get their just dues. I didn’t sit around and mope about it. I went out and did something else about it.”

Kesler joined Van Eaton in the original lineup of the Sun Rhythm Section during the mid-’80s, along with Sun rockabilly titan Sonny Burgess, ex-Johnny Burnette Trio lead guitarist Paul Burlison, pianist Jerry Lee “Smoochy” Smith (he was on the Mar-Keys’ 1961 smash instrumental “Last Night”), and bassist Marcus Van Story. “I went with those guys for a while,” said J.M. “Then they started traveling all over the world. I didn’t want to do that. I couldn’t do it. I had other obligations. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to, but I had other financial obligations that I had to take care of here, so I couldn’t be gone that long.” Van Eaton was replaced in the band by former Elvis drummer D.J. Fontana, though he did appear on their Flying Fish album “Old Time Rock ‘N Roll.” A few years ago J.M. released his own aptly titled vocal CD, “The Beat Goes On” (he also played harp on the set).

When contacted in Memphis, Van Eaton was planning his Stomp set. “I’m playing with a guy named Deke Dickerson, which I’ve never met before,” he said. “I’ll just be the drummer, I guess. I may do ‘Flyin’ Saucers Rock & Roll’ and ‘Red Hot,’ which I try to do on shows. Whatever works for them. But I’m going to have to let them make the call on that. I’m sure what we’ll do is songs that I played on, hit songs. And there’s enough of them to fill up a whole set, so we’ll probably do songs that I played drums on.

“I can tell these stories about the records. We’ve got enough Jerry Lee Lewis records, enough Riley records, ‘Lonely Weekends,’ and anything else they want to do. Warren Smith’s ‘Uranium Rock,’ that was a pretty good little record,” said the man who drove Warren’s thundering original. “I’m going to come in there and show up and play drums. And if I have to play an hour drum solo, I guess that’s what I’ll do!”

To see and hear Van Eaton and a host of other unsung rock ‘n’ roll heroes at this October’s concerts, buy your tickets to the 2015 Ponderosa Stomp right here.