What can you say about the beatific bombast that is Gary U.S. Bonds? The all time conquering barbarian of Beach Music, along with his sax-honking sergeant-at-arms Daddy G, stormed the Eastern shores beginning in 1961 with such dance hall war cries as “Quarter To Three,” “Twist, Twist Señora,” “Dear Lady Twist” and “School Is Out” — not to mention the shamanistic unreleased masterpiece “I Wanna Holler (But The Town’s Too Small.” And he’s bound to coup the room with Los Straitjackets laying down the sonic blast behind him.

—

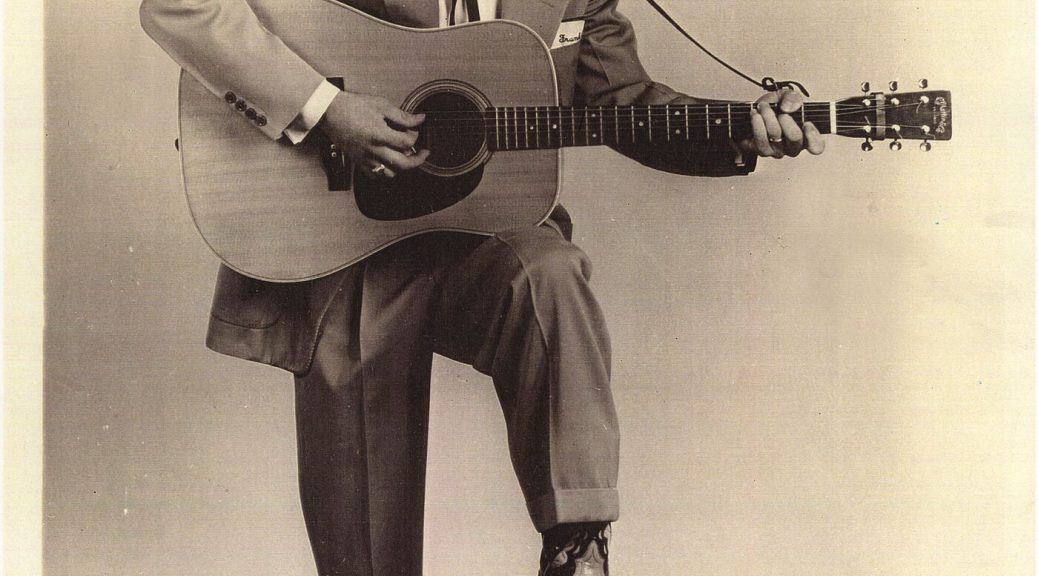

Until Gary U.S. Bonds came along, Norfolk, Virginia was known as a naval town rather than a rock and roll recording capitol. Gary’s string of pounding early ‘60s hits, led by the classics “New Orleans” and “Quarter To Three,” changed all that in a hurry. Under the brash production aegis of Legrand Records owner Frank Guida, who ran a Norfolk jazz and R&B record shop called Frankie’s Birdland and developed a booming, reverberating studio sound all his own, Bonds became a star built to last a lot longer than Legrand did.

Unlike so many of his peers who were permanently relegated to the oldies circuit after the British invaded our shores, Gary admirably hung in there when the hits stopped coming, mounting a highly successful comeback campaign when Bruce Springsteen and Miami Steve Van Zandt produced his 1981 album Dedication. Bonds will rock this year’s Stomp with his thundering hits, as fresh and bracing today as they were when they first rolled off the presses into eager teenagers’ hands from coast to coast and around the globe.

NORFOLK DOO-WOP BEGINNINGS

Although he was born in Jacksonville, Florida, Gary Anderson moved to Norfolk with his family when he was two years old. As he grew up, Gary managed to locate some fellow doo-woppers to harmonize with under the street lights. “I had a group called the Turks,” he says. “We never really worked anywhere, except on the corner. But we did a couple of talent shows, and we came in second each time. Couldn’t come in first–they had a group there called the Humdingers who were really good.”

Indeed they were. Led by General Norman Johnson, the Humdingers morphed into the Showmen, who ventured down to New Orleans and cut the 1961 hit “It Will Stand” for Minit Records under Allen Toussaint’s direction. Johnson later fronted the Chairmen of the Board on their 1970 million-seller “Give Me Just A Little More Time” for Holland-Dozier-Holland’s Detroit-based Invictus label.

“My main idol was the late Clyde McPhatter. He was with the Drifters, and then he went on his own,” says Bonds, who also dug the mighty Little Willie John. “Oh, there were many guys. The Turbans–I was into groups then. The bird groups, the car groups. They finally got around to coming into Norfolk, to a place called the Booker T. Theater. It was a black-owned theater. I used to go down every weekend and catch the groups when they came in: ‘Boy, I’d sure like to be up there, one of those guys!’”

The Bronx-raised Guida would help make that happen. Given to bold and rather shaky proclamations (“The Norfolk sound, I think, is what saved rock music,” the late producer once told me in all seriousness), the Italian-born Guida was bitten by the calypso bug while stationed in the West Indies during World War II, and he performed as “The Calypso Kid” in both Port of Spain and in Harlem after he got back home. Guida relocated to Norfolk in 1953 and established his record emporium the next year at 817 Church Street.

“I bought a record shop in a black neighborhood, not because I wanted to be a retailer, but I wanted to learn all I could about R&B just like Ahmet Ertegun did,” said Guida. “I started from the ground up. Then I gambled everything I had, including my home, to start a label.”

“NEW ORLEANS”

Young Gary dropped by Guida’s store now and then, often in the company of a local bandleader/pianist. “Sleepy King was his mentor. He sang sometimes with Sleepy King’s band,” said Guida, who launched his Legrand label in the autumn of ‘59 with “High School U.S.A. Virginia” by Tommy Facenda, a former member of Gene Vincent’s Blue Caps. Soon thereafter, Guida added a recording studio to his mini-empire. “I bought a studio that was folding up on Colonial and Princess Anne Road,” he said. “The very first recording I did at my very own Norfolk Recording Studio was ‘New Orleans.’”

“That was the only studio we had in Norfolk,” says Gary. “The guy who was running the equipment (Joe Royster) was actually a shoe salesman who was a friend of the guy who owned the studio. From shoe salesman to producer and engineer!” Guida and Royster had originally cooked up the pulverizing “New Orleans” for singer Leroy “Bunchy” Toombs. “The reason Bunchy didn’t do it was because Bunchy wanted to record his own songs,” explained Guida. So the fledgling producer chose newcomer Gary to wax the anthem instead.

“That was written by Joe, the engineer, the shoe salesman,” says Gary. “He was into country and western. Naturally, we couldn’t do country and western. So they told me to take it home, and see if I could change it around to whatever style I had, ’cause nobody knew then. And we did.

“(Guida) had asked me about a year, a year-and-a-half before if I would record when he started up his label and his studio, and I agreed. He owned the local record shop in the black neighborhood there, where we used to go and buy all our records. So he knew that we sang, because he used to pass by the little corner that we sang on,” says Gary. “He’d stop and listen for a while (and say), ‘Hey, you guys sound pretty good!’”

Guida had a unique approach from the outset when it came to aural reproduction, utilizing overmodulation on “New Orleans” to make the sound seem to jump right out of the grooves. “Nobody ever dared to experiment with echo systems like I did, with playback from one speaker tonally attacking the actual recording and creating ‘live’ recordings that were not live,” he asserted. “These were techniques that were unheard of!” Emmett “Nabs” Shields came up with an innovative double beat on his bass drum to further distinguish the record. But “New Orleans” would not bear the name of Gary Anderson when Legrand unleashed it in September of 1960. The odd artist credit read “By – U.S. Bonds.”

“There was a delicatessen next door to the studio,” says Gary. “A guy named Mr. Carr. And he was into United States Savings Bonds. In fact, he had the large signs ‘Bonds’ plastered all over the store, the flags, and the guy that used to sell the savings stamps, the Uncle Sam guy. And I think maybe he got the idea from Mr. Carr’s store.”

“He sold bonds,” said Guida. “It was about seven stores from where my studio was on Princess Anne Road. And I looked at the sign outside, and it said, ‘Buy U.S. Bonds.’ I walked in and I said to (Gary), ‘You know, when the record comes out, your name is gonna be U.S. Bonds!’” There was a bit more to his unusual strategy than that. “I changed his name to U.S. Bonds in order to get disc jockeys to think it was a public service recording that Uncle Sam had made in order to promote United States Bonds.”

Boosted by frequent spins on American Bandstand, “New Orleans” was the first major hit for everyone concerned–Gary, Guida, and Legrand Records. It peaked at a lofty #5 R&B and #6 pop in Billboard during the fall of 1960. Tenor saxist Earl Swanson, at one time married to hitmaking R&B chanteuse Ruth Brown, wailed hard on his solo, and the rest of Legrand’s crack house band, christened the Church Street Five (Shields, trombonist Leonard Barks, bassist Ron “Junior” Fairley, and pianist Willie Burnell), made quite a joyous racket behind Gary’s muscular double-tracked vocal.

“‘New Orleans’ is a fun song to do, because it’s an audience participation song,” says the singer. “It’s strange how you can get different people on different nights, and you get different reactions. You can change it a little bit, because it’s not a very complicated song,” says Gary. “I don’t know how we came up with that ‘Hey, hey, hey!’ I guess we were just short of words and didn’t know what to write, so we screamed something.”

Bonds displayed his ballad side on the flip, “Please Forgive Me,” the work of Bonds, Guida, and Royster. In the Crescent City, Gary had some competition from hometown favorite Big Boy Myles, who covered “New Orleans” for Johnny Vincent’s Ace label. Later on, the Kingsmen, Paul Revere and the Raiders, Wilson Pickett, Steve Alaimo, and Neil Diamond would wax their own versions, testifying to the song’s massive impact.

“QUARTER TO THREE”

“Not Me,” Gary’s first raucous Legrand followup, puzzlingly failed to chart altogether, although the Orlons revived it in 1963 for Philly-based Cameo Records and just missed the pop Top Ten (its flip “Give Me One More Chance” was a lovely doo-wop ballad). Then Bonds introduced his biggest hit of all, a juggernaut that started with sax-blasting labelmate Gene Barge’s two-part instrumental “A Nite With Daddy G,” which just missed denting the national hit parade. Barge was another Norfolk native, a veteran of the Griffin Brothers’ band whose jabbing horn sparkled on Chuck Willis’ 1957 R&B chart-topper “C.C. Rider” for Atlantic as well as the Atlanta blues shouter’s ‘58 followup “Betty And Dupree.” Gary and Gene went back a long way.

“His daddy was a chief petty officer in the Navy, and he was stationed in Norfolk,” recalls Barge. “His daddy and his mother Irene lived just a few blocks from me. So he grew up in my neighborhood, and I used to see him all the time. They used to hang out on the street corner singing.” Once they both ended up at Legrand, they proved prolific collaborators.

“Hy Lit in Philadelphia, one of the biggest disc jockeys in the United States at that time, started using ‘A Nite With Daddy G’ for a theme song. Harvey Miller used to play it too. Both of those guys were bigger than Dick Clark in Philadelphia. Gary said, ‘Man, I heard your song, and I put some lyrics to it!’” says Barge. “We went in and gave it to Frank, and Frank said, ‘Okay, that sounds like a good idea.’”

The result was the cacophonous party anthem “Quarter To Three.” “That was written primarily in the studio,” says Gary. “The producer believed in the song itself, and he says, ‘Why don’t you try to write some words to it?’ So we did, in the studio. It took a long time–about 10 minutes! We went in and recorded it right away. That was an easy one too. I had pretty easy times there.”

Guida’s explosive production technique on “Quarter To Three” reflected what went on in the sanctified pews of a high-profile local evangelist. “That was my full intention, to do ‘Quarter To Three’ as you would if you were going by the black churches, and hearing the excitement,” he said. “I wanted to capture some of the excitement and sound that emanated from Daddy Grace’s House of Prayer, on Princess Anne Road and Church Street.

“I slowed it up, described a party emanating from a room next door where the door would be open, and things would come out, where you could hear that there was something going on in the next room. Then the door opens, and there you are. Daddy Grace used a lot of trombone in his church. We did just that.”

Bonds vividly described a joyous all-night shindig in the narrative of “Quarter To Three,” Barge receiving a prominent name check and blowing just as hard as he had on “A Nite With Daddy G.” In June of 1961, Gary saw his brainstorm perched at the top of the pop hit parade for two glorious weeks (the haunting minor-key “Time Ole Story” provided stark contrast on the B-side). A lot of other musicians took note—Chubby Checker, the Kingsmen, Chuck Jackson, the Sir Douglas Quintet, and the Strangeloves all cut versions in years to come.

The success of “Quarter To Three” led to the issue of Gary’s first long-player, Dance ‘Til Quarter to Three with U.S. Bonds, which sailed all the way to #6 on Billboard’s pop album listings. Along with the doo-woppish ballads “One Million Tears” and “I Know Why Dreamers Cry” and an insistent “That’s All Right,” the album featured a sly revival of Cab Calloway’s singalong chestnut “Minnie The Moocher,” a trip to Tin Pan Alley via the sumptuous “Don’t Go To Strangers,” and the echo-laden rocker “A Trip To The Moon,” a recasting of the Church Street Five’s then-recent “Fallen Arches.” “That was Daddy G’s instrumental. They didn’t even bother to re-record that,” claims Bonds. “They just put the voice on right over the top of the instrumental track. We were short of songs for the album, and time. So we just started tying anything on there we could find around.”

“SCHOOL IS OUT”

The album also included Gary’s next smash, “School Is Out.” The singer wrote the irresistible rocker with Barge, who happened to be a high school English instructor when he wasn’t wailing at Legrand. “Daddy G, at the time in Virginia, was a schoolteacher,” remembers Bonds. “He started talking about he was glad that school was letting out, so he didn’t have to bother with the kids anymore. He could get to his music. And we started writing about it that night. Him and I and a few drinks…” The Top Five pop smash finally restored the singer’s first name to his professional billing: he was now answering to Gary (U.S.) Bonds. The atmospheric “One Million Tears” was a strong B-side.

Naturally, when it was time for the kiddies to return to class in the autumn of ‘61, Gary and Gene dreamed up the perfect sequel: “School Is In,” which also charted for Bonds. “We figured, ‘Well, we got this thing rollin’, let’s hang in there with it!’ ‘School Is In,’ ‘No More Homework,’ the whole trip. But ‘School Is Out’ actually turned out to be the biggest seller.”

“We would go to the studio almost every evening,” remembers Barge. “We’d go over there. And if we didn’t go over there and we’d get missing, Frank would call us: ‘What happened to you guys? Where are you? Gene, you know, you have to stay in touch. You guys, I know you’re out carousing around, drinking and stuff.’ He’d be on me and Gary’s case all the time. So we would go over there and work on the material.”

“DEAR LADY TWIST”

Guida’s enduring love for calypso reared its head on Bonds’ next Top Ten pop hit late that year, the infectious “Dear Lady Twist.” “It’s an old island song that we changed the words around and just put a straight backbeat on it. And it sounded different,” says Gary. “It was one song that the producer, who was stationed in the islands during his stint in the Army or Marines, or whatever he was in, he enjoyed the music, brought it back, and said, ‘Let’s try this!’”

“We did ‘Dear Lady Twist’ because Frank twisted his arm to do it,” says Barge. “Frank figured he couldn’t beat Chubby Checker out on the Twist stuff, so we’d do a little twist-calypso thing to it. That was his gimmick, so it would have a different presentation from just straight-out Twist music.”

“It was mainly my thing,” admitted Guida. “I think you can hear the West Indian influence, but it wasn’t an island song. I don’t think there ever was an island song that had that kind of approach. I thought it was a cute idea to have a West Indian woman, or an elderly woman, being the subject of dancing, of participating. I always tried to put out things that people would say, ‘Gee, I never heard that.’” “Havin’ So Much Fun,” one of Gary and Gene’s greatest creations, occupied the flip side and ranks as one of Bonds’ wildest rockers ever, with plenty of incendiary Barge sax behind Bonds’ fiery vocal.

“TWIST, TWIST SENORA”

Bonds stayed on an island-tinged kick on his next Legrand release, “Twist, Twist Senora,” another Top Ten pop entry during the spring of ‘62 with the savory rocker “Food Of Love” installed on the B-side (as usual, both songs emanated from Guida’s in-house sources—various combinations of Barge, Royster, and Guida himself). Gary was by now a consistent certified hitmaker, spending quality time on the road with some of the biggest stars of the era.

“You’d do like 32 days straight, all by bus,” he says. “You might get to do two or three days without seeing a hotel. No showers, no nothing. You do the show, you get back on the bus, you go do another show, get back on the bus. Maybe you’d stop at a hotel somewhere if you had time and get a shower. That bus was funky, man, I’ll tell you. We had a lot of soul on that bus. Everybody in the world. There would be the band, whatever band that was. Timi Yuro, Jo Ann Campbell, Chubby Checker, the Shirelles, Drifters, Coasters, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry. Every now and then Dick Clark, he’d slide in there and get out of the limousine just to show his face.”

“SEVEN DAY WEEKEND”

Twist Up Calypso, Gary’s second Legrand album, took Guida’s obsession with island ditties to the absolute max as Bonds did his best to cope with the daunting task of updating “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song),” “Mama Look A Boo Boo,” “Naughty Little Flea,” and “A Woman Is Smarter (In Every Kind Of Way)” into something Twistable. Fortunately, he was able to rock and roll unencumbered on “Seven Day Weekend,” his next single, which broke the mold by emanating from outside Guida’s inner circle—it was penned by Brill Building mainstays Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman.

Once again, the flip was a winner too. “Gettin’ A Groove,” another Bonds/Barge copyright, deserved a better fate than being tucked away on the B-side of a hit. “That was one of my favorites, that and the flip side of ‘Dear Lady Twist,’ ‘Havin’ So Much Fun,’” notes Gary, who lip-synched “Seven Day Weekend” in the Richard Lester-directed British film musical It’s Trad, Dad!. He shared screen time with Gene Vincent, Chubby Checker, Gene McDaniels, Del Shannon, and a passel of English trad jazz bands. But there was no trip to the U.K. involved.

“We did it in New York, my part. It took about 10 minutes. Paid me a lot of money, I went home, that was it,” says Bonds. “I went to see it. They showed it in my hometown. I was so embarrassed, because I had gathered up all my friends to tell ‘em, ‘Hey! I’m in a movie!’ And then they blew it up outside, like I was the star of the show in my hometown. Big picture of me and the whole thing. Everybody’s flocking down to see it, and I went the first day for the first showing. God, it was awful. I got out of town right after that!”

Bonds threw down the gauntlet in the general direction of some of his chief rock and roll rivals in “Copy Cat,” which barely charted during the late summer of 1962. “We got a lot of flack behind that one, because we were actually saying that most of the people that were coming up after we started were really trying to do what we were doing, especially out of Philadelphia,” he says. “So we were bad! We were saying it on record. They didn’t like that very much! Everybody got a little teed off about that.” “I’ll Change That Too” provided quite a change of pace on the opposite side, a relaxed number that was also cut that year by Chicago bluesman Jimmy Reed as “I’ll Change My Style” on the Vee-Jay logo.

Maybe some radio programmers held it against Bonds as well, because neither “Mixed Up Faculty” (another clever school song) nor its flip “I Dig This Station”—an obvious natural for extensive airplay–cracked the pop hit parade as his next release. Somehow success similarly eluded the storming “Where Did That Naughty Little Girl Go,” despite Barge’s blasting sax solos and Gary’s lung-busting vocal. The same fate befell “I Don’t Wanta Wait” and the double-sided punch of “Mixed Up Faculty” and “She’s Alright.” In fact, nothing else Gary waxed for Legrand ever made so much as a ripple on the charts, though he stuck with Guida into 1968. Daddy G wasn’t so patient. He moved to Chicago in 1964, locking down a staff producer/arranger gig at Chess Records that also included an album of his own and several 45s.

Quite a few subsequent Bonds releases on Legrand might well have stirred up some chart dust had they been rolled out a few years earlier. Before 1963 was over, he unfurled a smoothly harmonized “My Sweet Ruby Rose” and an insane two-part revival of the jazz evergreen “Perdido” that came complete with an emcee introducing Gary and crowd noise but sounds as though as it was done at Legrand (it also afforded Barge plenty of stretch-out time).

There were more attempts at launching new dance crazes (“Do The Bumpsie,” “King Kong’s Monkey”), a shot at making a guitar-driven rock track to compete head-to-head with the Brits (“Oh Yeah – Oh Yeah,” with a band billed as the Stompers), and a funky 1965 workout, “Beaches U.S.A. (That’s Where The Action Is).” The tempo-shifting screamer “You Oughta See My Sarah” was inexplicably credited to U.S. Bond and the Rhondels (Bill Deal’s beach music group had signed with Guida). 1966 brought the answer song “Take Me Back To New Orleans” (Jimmy Soul had already tried the same tune out on Guida’s S.P.Q.R. logo with a different destination: “Take Me Back To Los Angeles”). “I thought that was the better of the ‘New Orleans’ songs myself,” Gary says, even if the sales figures tell a different tale.

Speaking of Jimmy Soul, he ended up with a 1963 pop chart-topper thanks to another of Guida’s island-rooted retreads, “If You Wanna Be Happy,” which the producer had originally intended for Bonds. “I offered Gary that song,” said Guida. “He turned it down. I could see that he wasn’t really going to do what I wanted him to do. So I said, ‘Okay, fine—don’t worry about it.’ So I went into the studio with Jimmy.”

Towards the end of his extended run with Guida, Bonds was veering into more soul-oriented directions. There was plenty of call-and-response intensity to “My Little Room;” “Send Her To Me” was a full-fledged soul grinder, and the powerful ballad “Call Me For Christmas” showed Gary was capable of a lot more than a non-stop diet of houserockers. “I never thought anybody heard that other than the people around Norfolk,” he says of the latter. “It was big in Norfolk, Virginia, I know that.”

FROM FRANK GUIDA TO SWAMP DOGG

Gary exited Legrand after eight years, ready for new vistas. “I guess we were running out of material and out of ideas,” he says. “That was one of the reasons I left Legrand also. The ideas were getting very slim, and very dumb.” It didn’t take Bonds long to find a new label and a new producer. Stomp favorite Swamp Dogg was still listing himself as Jerry Williams, Jr. when he produced and co-wrote the funk-laden “I’m Glad You’re Back” on Bonds for the tiny Botanic label in the fall of ‘68.

Bonds and Williams also collaborated on Gary’s stomping “The Star” and found a far bigger outlet for the Williams production in 1969: Atco Records. But the promising connection proved to be a one-off. The following year, Gary surfaced on Juggy Murray’s New York-based Sue imprint with a violin-enriched “One Broken Heart,” Dogg still at the production helm. Its flip “I Can’t Use You In My Business” showed Bonds was quite conversant with sizzling soul.

Gary and Jerry were also writing for other singers at the same time. Doris Duke hit big in 1970 on the R&B lists with their “To The Other Woman (I’m The Other Woman)” on the Canyon logo. Freddie North did a fine job with the duo’s “She’s All I Got,” his soulful 1971 rendition for the Mankind label making a Top Ten R&B showing. But that was nothing compared to the impact of Johnny Paycheck’s country cover later in the year, which just missed topping the C&W hit parade. “I got into country by being in Virginia,” Bonds notes.

THE BOSS AND GARY’S BIG COMEBACK

During the ‘70s, Bonds was a frequent oldies circuit rider. One memorable Chicagoland show in 1972 found him headlining a bill with Johnny Thunder, Bobby Lewis, the Five Satins, Cornell Gunter’s Coasters, and Danny and the Juniors–at a fundraiser for Richard Nixon’s presidential campaign! But Bonds staged an amazing comeback in 1981 that sent him right back into the spotlight. Springsteen and Van Zandt, avowed longtime fans of the singer, recruited the E Street Band and other handpicked rock musicians to back Gary on his EMI America album Dedication, which contemporized Bonds’ sound yet recaptured the happy vibe of his heyday.

The thundering title track was an accurate homage to Guida’s patented sound, Clarence “Big Man” Clemons assuming the all-important sax slot that Daddy G held down for so long. Bruce stepped up in a vocal duet role for the delightful rocker “This Little Girl,” the Springsteen composition just missing the pop Top Ten. A second duet, an updated treatment of the Cajun perennial “Jole Blon,” also charted. Gary tackled songs by the Beatles, Bob Dylan, and Jackson Browne on the LP, its widespread success meaning that Bonds would no longer be limited to the oldies arena.

The same all-star cast reconvened the next year for Gary’s EMI America encore album On The Line. Springsteen contributed no less than seven songs to the project, including a splendid rocker, “Out Of Work,” that earned Bonds another trip to the pop hit parade. There was also a nice remake of the Box Tops’ “Soul Deep” and two titles, “Turn The Music Down” and “Bring Her Back,” that Gary wrote with his daughter, Laurie “Lil’ Mama” Anderson, who also sings backup with Bonds’ band, the Roadhouse Rockers.

Her mother, also named Laurie (aka “Big Mama”), boasts her own impressive musical resume. She was a charter member of the Love Notes, whose “United” was a 1957 doo-wop classic on Danny Robinson’s New York-based Holiday label, and made solo singles for End Records as Lucy Rivera (1959’s “IFIC”) and the Guaranteed imprint as Laurie Davis (“Don’cha Shop Around,” a Richard Barrett-helmed 1961 answer to the Miracles’ “Shop Around”). Big Mama married Gary in 1962, the two cutting an unissued duet for Legrand, “Guida’s Romeo & Juliet.” She also occasionally airs out her pipes with the Roadhouse Rockers. Along with a couple of new CDs (2004’s Back in 20 for M.C. Records and Let Them Talk in 2010 on GLA), Bonds has penned his autobiography, That’s My Story, in recent years.

Since it’s a safe bet the Ponderosa Stomp will rock until “Quarter To Three” or even longer, what better way to groove all night long than with the relentless rock and roll of this legend? With Gary U.S. Bonds, the party never stops.

–Bill Dahl